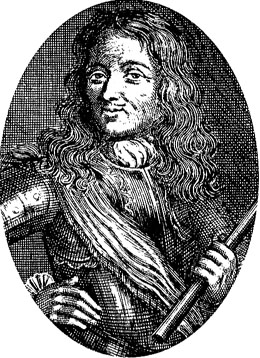

Louis-Henri de Pardaillan de Gondrin, Marquis de Montespan

Born in 1640, to Roger-Hector de Pardaillan de Gondrin, Marquis d’Antin, and Marie-Christine de Zamet de Murat, Louis-Henri enjoyed a pleasant childhood and grew up to be a dashing, handsome and gallant gentleman.

Charming and with good manners, Louis-Henri was a favourite of the ladies and managed to win the most beautiful woman of France for himself, as he said himself…. but little did he know what that would mean for his future.

Said most beautiful woman of France, was Françoise de Rochechouart de Mortemart, who later called herself Athénaïs, and actually engaged to someone else. Her family, although of ancient nobility, had some money problems and so it took a while to find a groom willed to settle for a not so big dowry. As a groom was then found, one Françoise was quite happy with, this groom got involved in a duel which resulted in the demise of Louis-Henri’s brother. The groom had to flee France and the engagement was cancelled.

Françoise’s engagement ended with a proper scandal and not just did she lose her groom, but also her reputation was in danger. People might say that she involved herself with someone who broke the law regarding duels and killed a man, then fled, like a coward, to Spain.

She hid herself away and one day an unexpected visitor knocked on the door of her Hôtel. Louis-Henri. The latter was, of course, deeply touched by the sudden demise of his brother… and so was Françoise. Both wallowed in sorrow together, talked about nothing and everything at the same time, forming a friendship, that soon, visit after visit, grew stronger and into feelings beyond mere friendship.

Thus Louis-Henri asked for the hand of this lovely and pious girl, which was so concerned on his behalf and mourned his brother as much as he did. It was a decision guided by the heart and not so much the mind, for Louis-Henri could have easily married someone with a larger dowry. On the other hand, Mademoiselle Françoise, although her dowry was small, could have also found someone with more prestige.

And there was one big problem: while the father of the Marquis de Montespan was well-respected and an adviser to the state, the uncle was a bit of an issue. He was a prominent member of the Jansenism sect and therefore pretty much a heretic. With a Jansenist uncle, it was impossible for the Marquis de Montespan to get a position at court, which in turn wasn’t too good for Mademoiselle Françoise.

Nevertheless, both were willed to enter the holy bonds of marriage and did so a mere week after the scandalous duel took place. On January 28 in 1663, Louis-Henri de Pardaillan de Gondrin married Françoise de Rochechouart de Mortemart at Saint-Sulpice, making her the Marquise de Montespan.

The marriage started of well. Both were equally in love with each other and the Marquis very pleased with what a lovely and virtuous wife he had found himself. Madame la Marquise became pregnant in a swift as well, what else could he wish for? Money. The dowry of 60000 livres was not trusted into their hands, but into that of the groom’s parents, from said dowry the newlyweds only received a small amount as well as a small sum from the bride’s parents as yearly allowance.

Marquis and Marquise moved into a quite modest home in the Rue de Taranne, maybe a bit too modest, but they could not afford more. Louis-Henri was forbidden to appear at court and with their marriage, his wife had lost her position as well. Previously she served as fille d’honneur to Madame, but a married woman can not be a fille d’honneur. Yet the Marquise was especially now expected to appear at court, to dance at balls and participate in ballets, in order to represent her husband through her grace and beauty, which maybe at some point, if she did well enough, would remove the ban on him. All of that is of course quite expensive, thus financial problems were granted.

Louis-Henri, instead of assisting his wife by leading a life of high moral standard, did the opposite. He always had been very fond of gambling and wasted all of their allowance, meant to last for a year, within weeks. Not good. He amassed debts and in order to pay them, borrowed money wherever he could get it. He borrowed 24000 livres from his mother against the dowry, their yearly allowance was 22500 livres, and another 18000 livres from his parents, not just in his own name, but in that of the Marquise as well.

Shortly later, he ran up debts of 1500 livres with a Monsieur Remy Marion, another 1800 with the carriage-maker Monsieur Jean Opéron, and 900 livres with a master wheelright Monsieur Jean Herbert. These Messieurs demanded their money, but the Marquis de Montespan could not pay them and thus was in danger of immediate arrest for inability to pay. The danger grew as the Marquis was then unable to pay another 2170 livres, this time to two merchants. You can imagine what went on the maison Montespan as Madame got wind of it. To prevent the impending arrest of her hubby, the Marquise dragged him to two Parisian lawyers in order to have them set up an arrangement regarding the debts.

Luckily for Monsieur de Montespan, the merchants could be persuaded to settle for the payment of 1000 livres instead of the full 2170 livres. If it taught him something, the lesson did not last, for Monsieur continued to amass debts… and he did not seem too bothered to pay them back. Thus Madame had to sort it out again and again. All of that was, of course, not very good for their marriage and at one occasion Louis-Henri even pawned his wife’s beautiful pearl earrings for a bit of cash.

At some point it dawned on Louis-Henri that all of this made it not more likely, but less likely, to gain a position at court and with it a regular income. So, he sought means, not being without ambition to win some glory, to make a fortune. The court was out of the question, but the army was not. An opportunity presented itself as the Duc de Lorraine did not cede the town of Marsal to Louis XIV, as he had agreed to do. To change the mind of the Duc, Louis XIV said he will move some willing troops there and the Marquis de Montespan was eager to be part of it as soon as he heard the news…. thinking that perhaps if he did his job well, Louis would also allow him to appear at court. It was a chance he could not miss, even if he had to make new debts for it.

A gentleman of his rank was expected to pay for his men, arms, horses and costs of travelling and if he had not gambled away so much money, it would have been affordable for the Marquis as well. But, alas, he had to go asking for money again. He borrowed 500 livres and then, in company of his wife, went to a moneylender in order to borrow another 7750 livres, on the condition it would be only used for military expenses. Then he asked his father-in-law to grant him an advance of 2000 livres and talked his brother-in-law into giving him another 500 livres. Both father-in-law and brother-in-law having no clue about the whole debt issue. Also because Monsieur and Madame de Montespan were not yet of the legal age, twenty-five, to engage in lending and borrowing money. Thus all their activities in that department with various merchants and moneylenders had to be done in secret.

Of course, the money was not just used for military expenses, but also partly to pay off gambling debts… and in the end it was all for nothing. While the troops were on their way, including Monsieur de Montespan, the Duc de Lorraine gave the town to Louis XIV without further ado. Louis-Henri returned to Paris and a furious wife, 13000 livres wasted. The birth of their first child, Marie-Christine, did not much to improve the situation.

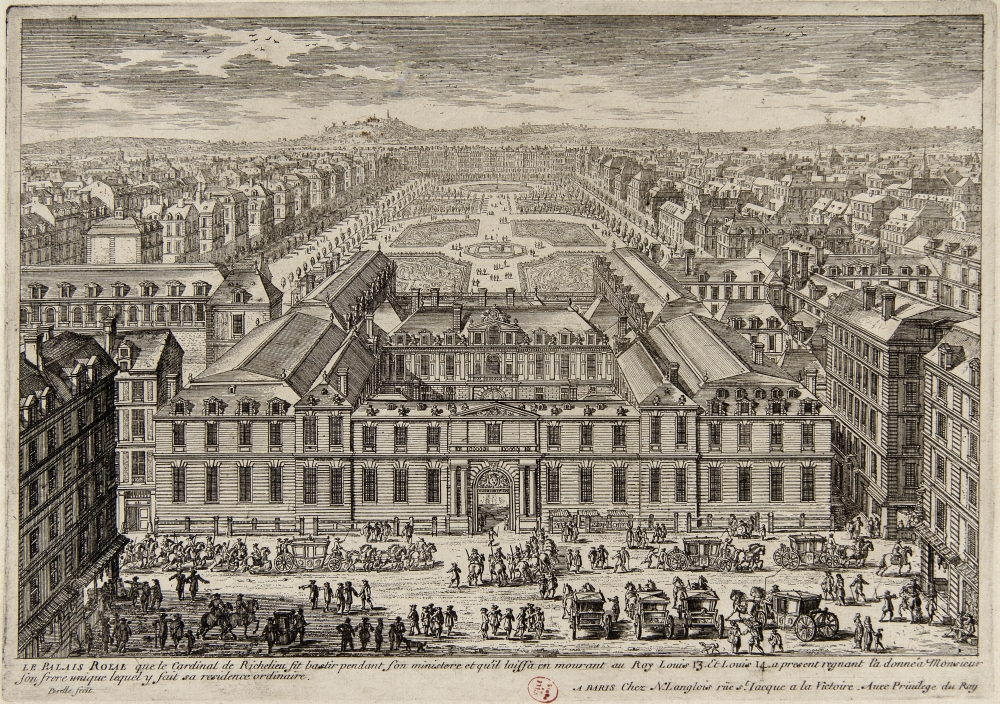

At least, with the help of Louis XIV’s brother, Madame de Montespan had a small success. Athénaïs was granted a position within the Household of the Queen, but the little income the position granted her was also needed to provide her with everything necessary for her new position. It put her into the spotlight and to make a good figure at court, she needed gowns of the latest fashion, maids to help her dress and do her hair, jewels and a carriage worthy of her rank.

In the meanwhile, her hubby returned to his old habit of gambling and returned from another failed military expedition with even more debts and no won glory. As their second child, Louis-Antoine, was born in 1664 new staff had to be hired and paid with money that was not there. Two years into the marriage, most of the love between them was gone…. and then it happened. Another Louis began to ogle Athénaïs. (You can read all about it in the article about her. Just click here.)

It was the King and the ogling encouraged by Athénaïs. In first the Sun King did not want her, but he changed his mind on the matter after a while and secret meetings between them were arranged. Athénaïs located herself closer to the Parisian residences, under the pretext it will allow her to serve the Queen better. Louis-Henri either pretended not to notice what was going on or really did not know in first. Even as the King spoke suddenly in the highest tones of him.

Louis-Henri enjoyed the warm rays the Sun casted on him, in form of praise for military achievements, and seems to have considered himself in a good situation then. At least in a position good enough, to kidnap a young serving girl, he had romantic feelings for, and to hide her away. The family of said girl was outraged and approached the King. Thus a bailiff was sent to recover the girl, which then was locked away for her own safety. With good reason, for Monsieur de Montespan then fought with the bailiff to get hold of the girl once more. In the end, he grew bored with her and gave her 20 pistoles (1 pistoles=10 livres) for her honour.

Louis-Henri returned to Paris afterwards, perhaps lured there by a Moliére play about a horned husband, but could not stay for long. The creditors knocked on his doors again. He was 48000 livres in debt by then.

While in first Louis-Henri might have pretended not to notice what his wife was up it, this changed as the Duc de Montausier, whose wife was a good friend to Athénaïs and helped to arrange the secret meetings, was appointed governor of the Dauphin… Monsieur de Montespan got the idea that his wife might have something to do with it. Could all the talk he had heard regarding his wife and the King be true? And that Moliére play… some claimed the horned husband was inspired by Monsieur, whose wife was making merry with his former lover, but there was also talk that said horned husband might be Monsieur de Montespan. Louis-Henri lost it.

He went on a rampage through the Parisian salons and denounced the King as adulterous. Until the whole city was bored with his endless tales and woe-is-me talk. After all, it was the King making merry with Madame de Montespan and complaining about it, in such a manner, was rather embarrassing, they thought. Why not make a profit of it? Have the King arrange for debts to be paid, or arrange for a fancy position or promotion, have the King buy and gift lands. All there was to do, was being quiet about the matter and perhaps even assist by backing away. Frankly, far worse things could happen to a husband than his wife being loved by the King. And a King was not a normal man, in which case the matter would be entirely different.

But Monsieur de Montespan was not the discrete type of man, not even when the King was involved. Thus he continued to rage and produced a text in which he denounced the King even more, comparing him to all sorts of biblical figures. He showed said text to la Grand Mademoiselle, cousin to the King and godmother to Monsieur de Montespan. “You are mad. You must not tell such stories.” was her reply, adding that people would not believe it anyway. And what he said was bordering on lèse–majesté, if the debts did not get him into prison, insulting the King like that surely would.

It did not change Monsieur de Montespan’s mind on the matter and he proceeded as he saw fit. The King had stolen his wife and the whole world should know it. It was his wife and thus he could do as he pleased with her, like taking her away from court… what he did not know then was, that his wife was pregnant with a child fathered by the King by then.

After his encounter with la Grand Mademoiselle, during which la Grand Mademoiselle saw what fury raged within the Marquis, she hurried to warn Madame de Montespan, who she considered to be a friend, and told her what her hubby had in mind. While she did so, on the terrace of Saint-Germain, Monsieur de Montespan sneaked into the palace and the rooms of his wife. He did not find her there, for the only one present was the Duchesse de Montausier… so he let his anger out on her. Athénaïs found her shaking in fear. The next time he appeared, he found both of them together. Mademoiselle reports he threatened both women and insulted them in the most vile manner, leaving them in fear for their very lives. And it got even worse. Louis-Henri began to stalk his wife, threatened her at every chance he got, one night he broke into the bedroom of his wife, perhaps thinking he would find her in company of the King, but she was alone and sure he would end her life. A other time, he lurked on the corridors to wait for her, just to insult her and leave again. Then he took to beating her. When he was not stalking or lurking, he loudly proclaimed in the salons he frequented how he was visiting the filthiest brothels Paris had to offer, in the hope to get an illness, which he then could forward to the King via his wife.

Madame de Montespan was terrified by his behaviour, who would not? Although she was the mistress of the King, the King could not do too much for her. She was married and not to him. Her husband was the one to decide over all matters regarding her… like the children. Therefor it was of utmost importance that Monsieur de Montespan remained in the dark when it came to his wife’s pregnancies. Otherwise he could claim the children as his own, even if they were fathered by the King… and that would mean he could use them against Athénaïs and Louis. He could take them away from them, hide them somewhere, and the King could do nothing about it. There was no law forbidding a husband to insult, beat or rape his wife. Thus Louis could not do much more than giving his mistress bodyguards and wait until Louis-Henri did something which would give Louis an opportunity to deal with him.

Athénaïs moved rooms and sought refuge with the Duchesse de Montausier, but she was not safe there from Louis-Henri either. Louis-Henri broke the doors to the apartment open, both women being inside, and tried to separate them in order to force himself on Athénaïs. As their servants rushed in to help the weeping and screaming women, he had to withdraw, but not without firing another round of insults at them. What had happened to the women spread in a swift and all of the court was talking about it. Soon rumours started that Monsieur de Montespan made plans to kidnap his wife and hide her somewhere in Spain.

Eventually, as Louis-Henri repeated his accusation regarding the Duc de Montausier and how he was only appointed because Athénaïs was involved, Louis XIV had a chance to do something about his mistress’ raging husband. By the means of a lettre de cachet. Louis-Henri was banished to prison for challenging the authority of the King in regards of the appointment of the Dauphin’s governor. After a week in prison, it dawned on Louis-Henri that he might have gone too far, not just with the King, but also his wife.

He was released with strict orders to stay away from court and to remain on his country estate. Surprisingly, there was only little protest from his side, thus rumours spread that Louis XIV had given Monsieur de Montespan a large sum of money. Louis-Henri left Paris for Gascony, taking with him his son and heir. Their daughter already lived at the country estate with his mother. Athénaïs was not allowed to see her son again until he was fourteen years old.

What Louis-Henri did as he arrived in the province caused another scandal. He ordered the main gates to be opened wide, for, so he said, his horns would prevent him from entering through a smaller gate. And as if this was not embarrassing enough, he then informed the gathered servants, in presence of his own children, that his wife had died.

He even went as far as to arrange a fake funeral, during which his children and family were dressed in full mourning, and a dummy of his wife was buried. After it, he rolled off in his carriage, draped in black and featuring large antlers on the roof.

His banishment to the province forced Louis-Henri to accept the facts. The most beautiful woman of France, his wife, was no longer his. He kept the horns on his carriage, but began to lead a quieter life. Yet he was not allowed to return to court, for his previous outbursts still lingered in the mind of King and mistress. Both feared that Louis-Henri might show up unannounced one day and the whole ado could start anew. Thus he was strictly forbidden to even pay a brief visit to the court when business made it necessary for him to travel to Paris for many years to come.

In the meanwhile, Louis-Henri became a sort of province patron. His wealth was not too great as he had to settle in Gascony, but after the death of an uncle, the Duc de Bellegarde, Louis-Henri laid claim to the inheritance. Louis XIV let him do so, but never officially recognised anything. Monsieur de Montespan moved châteaux and made improvements to the properties he claimed. He tried to act the gallant gentleman, but often his true colours could not be hidden. At one point, he fell in love with a Mademoiselle Riquet, daughter of an engineer, and proclaimed loudly he would marry the girl. Adding how he would write the Pope to have his marriage to Athénaïs annulled. As talk of this reached court, Monsieur Louvois swiftly put an end to it.

It was not until the 1690’s that Monsieur de Montespan was allowed to show himself at court again and when he did so, he always made sure to act as gallant as he could, especially when playing cards with his “daughters”.

Other times he was not so gallant when playing cards. Back in the province, he sat down in company of quality for a game of lansquet and lost his king of hearts. One of the ladies present teased by saying “That is not the king of heart which has done you most harm.” Alas, some wounds never heal. Louis-Henri dryly replied “If my wife is worth a louis, then you are valued at thirty sous.” To make sure the lady in question would not dare to tease again, he rewarded her with a good kick a little later during a masked ball.

Louis-Henri spent the last years of his life either at his country estates or at court, taking much pleasure in seeing his son rise in favour and glory. A formidable young man with close connections to the Dauphin. It surely must have pleased Louis-Henri to see the fall of his wife as well, who was by then no longer wished to appear at court for years already. Yet in his will, he is has many tender words for her and even made her his executrix.

Louis-Henri de Pardaillan de Gondrin died on December 1 in 1701, aged 61, in the arms of his son. He was not mourned by many. Madame de Montespan did was she was expected to do, she donned mourning and had masses said for his soul.