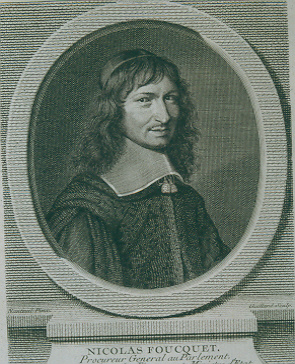

Nicolas Fouquet

Born in Paris into a wealthy family on January 27, 1615, Nicolas Fouquet made it to the heights of political power and fell very deep. His father, François Fouquet, was a member of the noblesse de robe and as such was a Maître des requêtes, a high-level judicial officer of administrative law, as well as Counsellor to the Parliament of Paris and Counsellor of State. Contrary to their own claims, the family was not always noble and made their fortune originally with the trading of cloth before they entered judicial offices and bought themselves into the Parisian Parliament as Counsellors.

Nicolas’ father married Marie de Maupeou, from a wealthy family of lawyers, in 1610. Her father Gilles de Maupeou was Contrôleur général des finances and worked closely with the Duc de Sully, faithful right-hand to Henri IV.

François Fouquet and Marie de Maupeou had sixteen children, of which eleven reached adulthood. All of their five daughters became nuns of the Ordre de la Visitation de Sainte-Marie, while their six sons pursued careers at court or Church. The oldest, François V (born 1611) made it to Bishop of Bayonne and then Archbishop of Narbonne. Basile, born in 1622 and called l’abbé Fouquet made it to chief of Cardinal de Mazarin’s secret police. Yves, born in 1629 was maître des requêtes like his father and the youngest two, Louis and Gilles, took Church and court positions. The first as Bishop and the latter as premier écuyer.

Nicolas was the second born son of François and Marie and was entrusted to the Jesuits of the Collège de Clermont (now Lycée Louis-le-Grand) for his education. In first, Nicolas was meant for a career in the Church as well and so received the tonsure in 1635. Although he was already treasurer of the abbey Saint-Martin de Tours and preparing for his intended Church career, his parents were not quite sure if this was the right career to pursue for him.

Nicolas was highly intelligent and showed an affinity for matters of law and at the same time was quite fond of science, chemistry and pharmacy. During his time with the Jesuits, he often assisted his mother in mixing remedies for the poor. (Marie Maupeou acted as patron for those in need and frequently visited the ill of the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris. She became the manager of the hospital Dame de la Charité de l’Hôtel-Dieu and the hopsital des Dames de la Propagation de La Foi as well as director of Hôpital des Filles de la Providence. After her death in 1681, a book was published containing plenty of receipts of the remedies she created herself to cure various illnesses. The Fouquet crater on Venus is named after Marie.)

According to the lawyer Christophe Balthazar, Cardinal de Richelieu advised Nicolas’ parents the boy should do a law degree instead of joining the Church. They followed the advice and Nicolas made his degree in law at the Faculté de droit de Paris. Already as teen, Nicolas held several important positions of responsibility. Nicolas was only eighteen as his father asked Cardinal de Richelieu for a position as Councillor in the Parliament of Paris. It did not work out, since Nicolas’ older brother was one already, but Nicolas managed to get a place in the Parliament of Metz the following year. In 1635, Nicolas’ brother joined the Church and the way was clear for him. Aged twenty, and with the help of his father, Nicolas bought himself the position of maître des requêtes and his father gives him a share of the Compagnie des îles d’Amérique, created by him on behest of Cardinal de Richelieu.

By then, Nicolas was already a well-made and wealthy man. His wealth got even bigger as a marriage with Louise Fourché was arranged. The two married on January 24 in 1640 and Louise brought a dowry of 160000 livres in cash, land in Quéhillac, another maître des requêtes position, and a pension of 4000 livres. As Nicolas’ father died in April 1640, Nicolas inherited quite a bit of his father’s wealth as well as a vast expensively bound collection of books.

Fouquet used a part of his wife’s dowry to buy himself land at Vaux, located between the royal residence of Vincennes and Fontainebleau, and started to call himself the Vicomte de Vaux. His wife was not able to enjoy their new country estate for long, she died in 1641 only six months after giving birth to their daughter Marie.

Following his father’s advice, Nicolas got involved in several shipping companies during this time by investing money and his wealth grew swiftly. He seems to be the born business man.

Fortunately for Nicolas, not much changed for him as the long time patron of their family, Cardinal de Richelieu, passed away and Fouquet finally decides to concentrate his efforts in service of State. Richelieu’s successor Cardinal de Mazarin seems to be just as fond of Fouquet. Between 1642 and 1650, Nicolas held various offices in the provinces and later in the royal forces. This way Fouquet got really in touch with the court for the first time and he seems to have made quite the impression, for he was allowed to buy himself the position of procureur général, Chief Prosecutor, in the Parliamnet of Paris. A position worth 450000 livres. Fouquet played his cards well by staying loyal to Mazarin as the Fronde raged through France. He made sure the Cardinal was informed of everything that happened at court and in France during his time in exile and secured the Cardinal’s own vast wealth. Nicolas made some more money himself as well, for during the Siege of Paris, he was in charge of the department of supplies.

With his new position in the Parliament, Nicolas Fouquet now belonged to the very elite of the noblesse de robe and he would climb even higher, matching the motto beneath the Fouquet family Squirrel-coat-of-arms “Quo non ascendet? ~ “What heights will he not scale?”.

Fouquet married again February 1651, aged thirty-six. His chosen bride is the fifteen year old Marie-Madeleine de Castille Villemareuil, with a dowry of 100000 livres. A bit less than what the first Madame Fouquet brought into the marriage, but the second Madame Fouquet made up for it by means of relations and a possible inheritance of 1500000 livres.

As Mazarin returned from his exile, Fouquet demanded the position of Surintendant des Finances as reward for his loyalty to Cardinal and received it thus. The decision to appoint him proved to be a popular one with the wealthy people of Paris and it allowed him full control over the Royal Finances. He decided how much was spent for what, which creditor was paid which sum and he was the one that held the negotiations with the financiers of the Crown. His position of procureur général within the Parlement de Paris also ensured that the financial transactions would not be investigated by anyone. With this move, Fouquet managed to make Mazarin somewhat dependent on his good graces. The mighty Cardinal had to apply for funds for the Crown to Nicolas Fouquet now, but Nicolas didn’t do his job half as well as he could have done.

The Royal Treasury was nearly empty and needed to be filled to finance King and Kingdom. Fouquet achieved this by making the conditions for creditors more favorable and creates new rights for them. The situation only improved briefly. Fouquet is soon forced to use his own name to lend money and the whole thing gets a little confusing even for him. Vast amounts of money move through the hands of Fouquet day for day, money meant for the Kingdom, and that of courtiers as well. Fouquet’s own fortune still grew, but that of the Kingdom was a bit of a mess. Its creditors and financiers were kept happy by the promise of aid and favours, while dubious operations took place to ensure the Crown had money in the Treasury.

This was not Fouquet’s only problem, Jean-Baptiste Colbert launched an attack against Fouquet in a paper on how to improve the financial situation of the Kingdom. Colbert was no friend of Nicolas and saw other ways to make France rich again, for example by improving the tax situation. Half of the taxes collected did not reach the Crown, because so many of those involved in collecting them kept a share for themselves.

As Mazarin died in 1661, Fouquet expected to be named Chief Minister of France. Little did he know that Louis XIV had already decided to rule himself and that people like Fouquet partly inspired this decision. Louis did not trust his Finance Minister and Colbert made sure this did not change by keeping the King updated on Fouquets transactions and undertakings. The wealth of the King’s Finance Minister surpassed that of the King by far. Fouquet had bought himself the port of Belle-Île-en-Mer, was able to give his daughter, by his first wife, a dowry of 600 000 livres upon her marriage, and was spending a fortune to have a palace build at Vaux. Fouquet collected expensive books, manuscripts, painting, statues, jewels, surrounded himself with the greatest nobles and greatest artists. Fouquet owned several grand Hôtels in Paris and hosted a party for Christina of Sweden. He was the richest man in France with a guessed wealth of 19 million livres.

For Louis XIV and Monsieur Colbert, the case was quite clear. Fouquet, who was supposed to make France rich, was getting richer himself, while France remained in financial trouble. It could only mean that Nicolas Fouquet was taking money from the King.

This became very clear to Louis XIV as Nicolas Fouquet invited him to visit Vaux-le-Vicomte for a magnificent fete on August 17, 1661. The display of wealth Louis XIV witnesses at Vaux, is the straw to break the camel’s back. As Fouquet invited Louis XIV and his court to Vaux, he had not really a clue that his fate was almost sealed and he no longer in favour. It was already decided in May that something must be done with him. He got too rich, too influential and above all it was rumoured he was involved in a plot to poison the King in 1658 and now he fortified his port and stores weapons and ammunition there… suspicion rose that Fouquet might intend to gather men there.

Louis XIV had learned to keep his true intentions very well hidden and tricked Fouquet, by hinting he might rise to an even higher office, to sell his position within the Parliament to the Crown. Fouquet did so without hesitation and now, without the position and privileges that protected him, Louis could strike.

Three weeks after the fateful fete at Vaux, on September 5, 1661, Fouquet accompanied the King to Nantes for the opening of the meeting of the provincial estates of Brittany and was dumbstruck as Charles de Batz-Castelmore d’Artagnan arrested him outside the council chamber.

His trial lasted for nearly three years and went not always according to the rules, which brought Nicolas Fouquet the support of the general public and many nobles, while the King himself acted as if he was on campaign. All of Fouquet’s belongings were seized, his papers searched for the slightest hint of betrayal, Belle-Île-en-Mer seized by Royal troops, his wealth confiscated. At the end, Nicolas Fouquet is found guilty of embezzlement, a crime that is to be punished by death. Luckily for Fouquet, only nine of the twenty-two judges opted for the death sentence and it was decided on banishment instead. Something Louis XIV did not like at all. He could not possibly allow Fouquet, who knows so much about the State, to walk free under the Italian sun or even worse, at a foreign court where he could work against him. Thus the Sun King turned the sentence of banishment into imprisonment for life and fires two of the judges for not acting according to his wishes.

Fouquet is swiftly brought to Pignerol in December 1664, a fortress at the other end of the Kingdom. There, Fouquet had two rooms at his disposal as well as two valets. Madame Fouquet was not allowed to write her husband until 1672 and was only once, in 1679, allowed to visit him. After thirteen years of imprisonment, in 1677, Fouquet was granted a little more freedom by receiving permission to walk the grounds on the old fortress. Fouquet was not the only guest of Pinerol. Antoine Nompar de Caumont, Duc de Lauzun, spent some time there with him. His cell being below that of Fouquet’s. A other, and probably the most famous guest of Pinerol was a man named Eustache Dauger aka The Man In The Iron Mask. This mysterious prisoner even acted as valet for Fouquet as his actual valet fell ill.

The conditions in the fortress were of course not the best for Fouquet. Certain comforts were granted to him, but the damp air and harsh cold in his cell were not good for his health. According to rumours, Louis XIV had planned to release Fouquet shortly before he died on March 23, 1680.

The official version of events is that Nicolas Fouquet died to due a stroke, after a long illness and during a visit of his son, the Comte de Vaux. His family did not doubt this version of events, but some accounts and rumours tell a different story. Monsieur Gourville writes that Fouquet was indeed released shortly before his death and Voltaire states this was confirmed to him by the Comtesse de Vaux later on. Robert Challes states in his memoirs a former clerk of Colbert told him Fouquet died in Chalon-sur-Saône due to indigestion or poison. Poison plays also a role in two rumours that state Fouquet died in the fortress, but was killed by either a unknowing Eustache Dauger aka the Man in the Iron Mask or by Bénigne Dauvergne de Saint-Mars, then governor of the fortress-prison.

Fouquet was buried a few days after his demise at Sainte-Claire de Pignerol and later taken to Paris to the Fouquet family chapel of the convent de la Visitation-Sainte-Marie.

One Comment

Susan Abernethy

Wonderful post Aurora. I’ve been looking for a good article about Fouquet for years.