The War of Devolution

Lasting from 24 May 1667 to 2 May 1668, the War of Devolution was Louis XIV’s war. His first chance to win glory on the battlefield and that he did.

It all pretty much began with Louis’s wedding and the marriage contract. The Infanta Marie-Thérèse d’Autriche married the King of France in June 1660 to seal the Treaty of the Pyrenees, which ended the Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659). Since she was the oldest daughter of Philip IV of Spain, there was of course the possibility that she, or the hubby, could lay claim to parts of Spain at some point. Thus the marriage contract featured a sentence in which Marie-Thérèse explicitly renounced all rights to her father’s inheritance… to make up for that, a dowry of 500,000 gold écus was promised to Louis XIV. But there was a bit of a problem.

The Franco-Spanish War had left Spain sans money. So, the dowry was never paid. Cardinal Mazarin, who negotiated the contract, and Louis XIV counted a bit on that, because if the compensation was not paid, so it was argued, the renouncing of claims was invalid. Which in turn meant, should the Spanish King die, Louis XIV could lay claim to Spanish territory in the name of his wife… and that is what he did in 1665.

Philip IV died on 17 September 1665 and was succeeded by his four-year old, physically and mentally disabled, son Charles. He was his only son, born during his second marriage to Mariana of Austria, who acted as Regent for the boy. Charles was thus a half-brother of Marie-Thérèse.

Pretty much as soon as the news of Philip IV’s demise reached France, Louis XIV claimed to parts of the Spanish Netherlands, the Duchies of Brabant and Limburg, Cambrai, the Marquisate of Antwerp, the Lordship of Mechelen, Upper Guelders, the counties of Namur, Artois and Hainaut, a third of the County of Burgundy and a quarter of the Duchy of Luxembourg for France. Justifying it with the fact that the dowry was not paid and due to it, his wife having a right to her father’s inheritance. That is also what gives the upcoming war its name. Louis pointed out that according to an old custom of Brabant, called the right of devolution, children of a first marriage including daughters -Marie-Thérèse in this case- have the right of inheritance over any children born during a second or third marriage.

So, Marie-Thérèse’s claims count more than those of her half-sister Margaret-Theresa, future wife of the Holy Roman Emperor, and the half-brother, who was now Charles II of Spain. French legal scholars concluded, based on the right of devolution, that the Spanish Netherlands are rightfully Marie-Thérèse’s and not Charles’… and what was Marie-Thérèse’s was thus Louis XIV’s. Since all of that involved old laws and such things, it pretty much hints that it was planned out for a while already. France had wealth on its side, but was surrounded by Spanish property. Although Spain and France were on friendly terms, this could always change and put France into a situation where it would be beleaguered by Spanish forces from all sides. One way to change that, was to break the circle by claiming the Spanish property for France. The marriage contract issue was a good explanation to do just that.

The Spanish Regent didn’t want to hear any of it, of course, and in turn pointed out that although no dowry was paid, the renouncement was still valid since the contract had been signed.

Louis wasn’t satisfied with that answer. Thanks to a rather skilled Finance Minister, he had quite a bit of money at his disposal and whenever he needed more, said Minister made sure there was more. This allowed Louis to expand his forced from 50,000 to 80,000 men without much hassle. On the other hand, Spain was still not off well in matters of money. They fought with serious economic problems, inflation and Portugal. It used to be ruled by the Spanish Habsburgs, but sought independence, which forced Spain to move a large amount of their military there.

What is bad for Spain, might be good for France. Thus the King of France got into contact with the King of Portugal and a treaty of alliance was signed on 31 March in 1667. Not that Portugal would have rescued Spain… but just to make sure nobody stood in Louis way. For that, he also had to deal with the Dutch.

The United Provinces were generally France-friendly. France had supported the Dutch in a previous war with Spain and both countries did enter a defence alliance in 1662. Again, just to make sure the road was free, Louis XIV sent someone over to test the mood. At that very point, the United Provinces were at war with England, which made them fear if they did not answer Louis’ call, he might go to the English and team up with them. The Dutch Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt suggested that the Spanish Netherlands be mutually divided. Such plans were already being debated from 1663 onwards, but the portion that Louis demanded for himself was a bit much for the Dutch and nothing could be agreed on.

The Spanish were not lazy either and approached the Dutch as well. Suggesting that both countries should combine their armies in case of a French invasion…. but Monsieur de Witt did not see it as a win-win situation. The Spanish forces were not the strongest. On top of it, Louis had the French emissary declare that if the Dutch teamed up with Spain, France will take it as declaration of war. Looking at his options, de Witt came to the conclusion that he would rather not have Louis XIV knocking on his door accompanied by an army.

The French-Dutch talks ended with nothing really being agreed on, but gave Louis the impression that he could go ahead with his plans. He was a young man eager to win himself some glory in order to establish himself as someone who knows how to war and in turn make the rest of Europe aware that France could either be their best friend or worst nightmare.

With Portugal and the Dutch Republic sorted, there still was one European power that could spit in his soup. The Holy Roman Empire. As part of the Burgundian Circle, the Spanish Netherlands, on which Louis XIV had his eyes, were subject of a special 1548 defence guarantee by the Empire. In the event of an attack, war could be declared on France. French diplomats approached and managed to come to an agreement with various states of the Empire, in which they pledged to deny their territories to foreign troops and to push for imperial neutrality. This meant that Louis’ plans were also protected against Imperial intervention. The road was free now.

On 8 May 1667, Louis XIV let the Spanish court know that he was still claiming the territories. His declaration was carried to every other European court, in a way that made clear Louis did not want to invade foreign territory, but merely take over the lands that were rightfully his own anyway. Calling the whole thing a voyage.

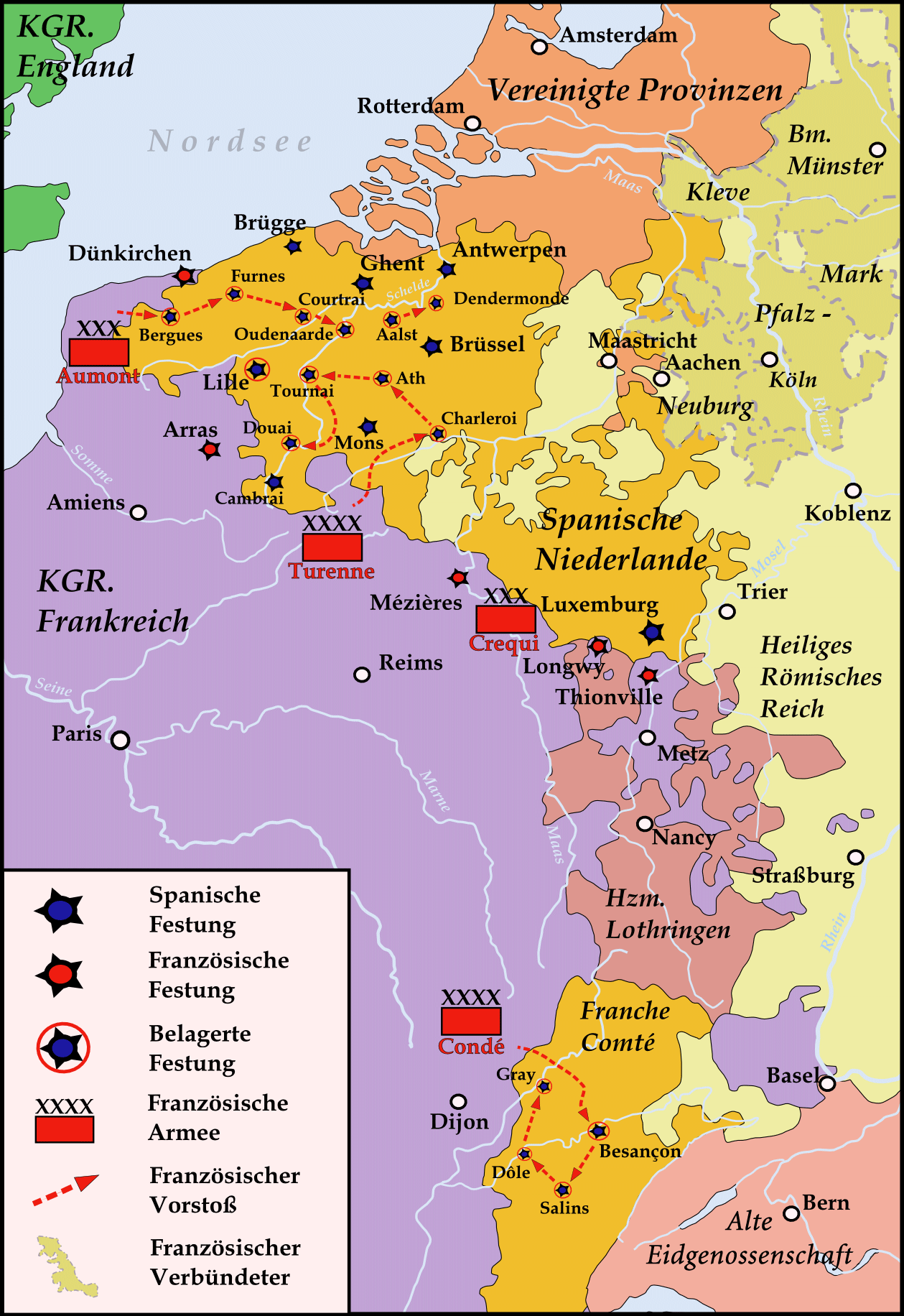

Around the same time, French forces numbering 51,000 men, which had been raised in only four days, deployed between Mézières and the sea. The main part of the army consisted of 35,000 men and was led by Louis XIV himself. Maréchal Antoine d’Aumont de Rochebaron was given command of another part of the army and placed himself to the left, at Artois. François de Créquy, Marquis de Marines, positioned himself to the right with his men. Being spread out like that, enabled every commander to enter the Spanish Netherlands at a moments note, while it prevented the Spanish from concentrating their forces at one spot. Instead of one big army, there were three to deal with. Three that outnumbered them.

On May 24 in 1667, sixteen days after the voyage was announced, the French forces crossed the border. While the French were well organised, the Spanish were poorly prepared for the whole thing. On top of it, they could not expect reinforcement from the mother country in the foreseeable future. There was no central organisation either. Every large town was responsible for itself, including their defence, which left them a bit vulnerable to sieges. Since only few Spanish troops were available, those were posted at the strongholds of the country, in order to hold them as long as they were able. Thus, while the French sauntered in, they hardly met a Spaniard on the way. Nor were there any large battles of army against army, the conflict was one of skirmishes and sieges.

Maréchal de Turenne was given supreme command of the French forces on May 10 and moved to take care of the first big obstacle. The town Charleroi, which, due to its location on the Sambre, dominated the connection between the northern and southern Spanish property. The Spanish did not have the men to hold it and destroyed the fortifications of the town, before abandoning the fortress. Turenne took over Charleroi on June 2 and had the fortifications reconstructed.

The French used Charleroi as their own stronghold for the next fourteen days, while the next moves were prepared. Either against Mons or Namur. The Spanish hurried to strengthen the towns…. in the meanwhile, Turenne moved his troops past Mons and took Ath. Without contest. The Spanish did not expect it.

It was Turenne’s goal now to cut off the area of Flanders, with its capital Lille, from the Spanish bases at Bruges, Ghent, Brussels, and Namur. To do this, he moved to Tournai. The main army reached Tournay on June 21 and surrounded it. For days later, on June 25, the French took over the town.

The voyage continued with Turenne marching west and the city Douai falling into French hands after a seven-day siege. Up north, Maréchal d’Aumont de Rochebaron took Bergues on 6 June and Furnes on 12 June. Flanders was now cut off from the sea. Turenne moved to attack Courtrai and the city was conquered on 18 July. Oudenaarde followed shortly after.

Turenne had isolated the most important Spanish fortresses of Ypres, Lille and Mons, but instead of immediately besieging these locations, he decided to first move against Antwerp. This move stalled between Ghent and Brussels. The small stronghold of Dendermonde, defended by 2,500 Spanish, held out against the French army. Maréchal de Turenne therefore pulled back at the beginning of August via Oudenaarde and prepared to besiege Lille instead.

The siege of Lille was the greatest challenge of the campaign and lasted from August 10 to August 28. The Spanish defenders were allowed to withdraw in exchange for capitulating the city, but the Marquis de Castel-Rodrigo, responsible for the Spanish troops, had no clue of it. After Lille had already fallen into French hands, he sent an army of 12,000 men to Lille, in order to help the defenders… which were already gone by then. This Spanish army met the Marquis de Créquy, who Turenne had entrusted to cover his siege, on August 31 and the Marquis forced the Spanish to withdraw again in a swift.

After conquering Lille, Turenne did one last move. On September 12, he took the stronghold of Aalst, thus breaking the connection between Ghent and Brussels. The French busied themselves with a loose blockade of Ypres and Mons afterwards, before withdrawing into winter quarter at October 13.

What Louis XIV had called a voyage, really turned out to be one… but his successful taking of town after town had consequences. The British were shocked and the Dutch rather worried. If he had such an easy game with the Spanish…. who would be next once the Spanish were off the table?

As the French were in winter quarter, the Spanish tried to get in a more advantageous position. In June, they already had gathered troops to sent to Flanders, but that didn’t work out. Juan José de Austria was appointed as commander of the planned army, but he had a bit of a tarnished reputation after a number of defeats in the war against Portugal. He assessed the conditions in the Spanish Netherlands pessimistically, thus delayed his departure with the pretext of the decision of a theological commission, which had declared itself against an alliance with the Protestant English and Dutch. In the end, further political complications meant that the Spanish army never arrived in Flanders.

Now, the Spanish turned to the United Provinces for help and the Marquis de Castel-Rodrigo inquired if some sort of financial support was possible. In return, he offered some nice trade customs revenues. Unfortunately for him, the Dutch were quite afraid if they would agree, Louis XIV would conquer them next. The fast progress of France, alarmed the Dutch greatly. For almost a century, France and the United Provinces had been allies against the Spanish. As France became a formidable trading power in the world and a major competitor to United Provinces in world trade, the Dutch in turn became more and more worried about French intentions.

Although they remained enemies of the Spanish monarchy, the Dutch began to wonder if Spain might not be a better neighbour compared to the aggressive France. The Spanish Netherlands served as a sort of buffer state between them… and God knows, what might happen if the area was in French hands. The Dutch thus hurriedly ended their war with England and offered to mediate in the war between France and Spain. Louis XIV declined. He had in mind to get the Dutch to agree with him on dividing the Spanish Netherlands between them… but the Dutch declined the idea in turn…. and now Louis was really considering to go to war against the Dutch.

The Spanish were however able to come to an agreement with Portugal. The Peace of Lisbon enabled them to now move all their armed forces against France.

Louis XIV was not lazy either. To keep the Spanish from making some sort of deal with the Holy Roman Emperor, French diplomats entered secret negotiations about a delicate matter. Charles II of Spain was a six-year-old child and due to his disabilities, nobody expected him to live long. If he died, the Spanish line of the Habsburgs would die with him…. and Spain would need a new sovereign. Both nations came to an agreement that, if this should happen, Spain was to go to the Emperor along with its colonies and the Duchy of Milan. France would receive the Spanish Netherlands, Franche-Comté, Navarre and the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily. Thus, the Holy Roman Emperor had no reason to involve himself in the current conflict, for the Sun King was only occupying territories he would get anyway.

The United Provinces, seeing the possible danger, tried to coalition against France in order to limit to the French expansion, but in a way that would not damage their relations with France. As if all of that isn’t complicated enough already, the English and Swedish got involved now too. Charles II entered secret negotiations with France to create an alliance and at the same time talked with the United Provinces to form an alliance against France. While Louis XIV did not come to an agreement with the English, the Dutch did… and that changed everything.

On 23 January 1668, the United Provinces, England and Sweden concluded the Triple Alliance, whose declared aim was to bring about the Spanish relinquishment of certain territories in the Spanish Netherlands and to persuade France to limit its claims… a secret part of the protocol also stated if the French King would extend his claims or was to continue his campaign of conquest, the alliance would use force to push France back to the borders of 1659. Not good.

The Dutch hurried to make it known to the French diplomats, and thus Louis XIV, that this alliance was not generally aimed against France but had the purpose of making Spain relinquish the specified territories. Louis did not buy it. He felt betrayed by what should be his ally. Especially because France supported the Dutch so often in the past, like in their cause for independence. Louis wanted revenge for this betrayal, which led to the Franco-Dutch war a couple of years later.

During the upcoming summer campaign of 1668, the Sun King intended to conquer as many Spanishlands as possible. He planned to throw those in, in case of peace negotiations. The Spanish ruled Franche-Comté was another piece of land he wished to call his own. It was isolated and practically devoid of Spanish troops. Louis instructed the Prince de Condé to undertake preparations for a winter campaign against the Franche-Comté, something the Spanish did not think would happen.

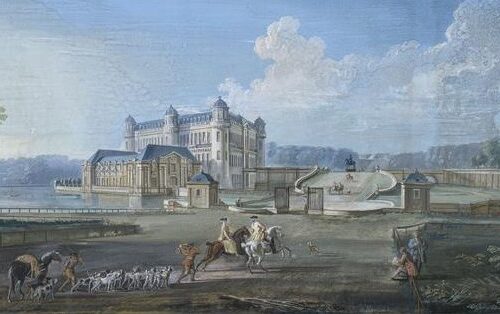

It was the first time in nine years that Condé was given command, after he fell out of favour during the Fronde. A second army of newly raised troops was set up and Louis XIV once again personally accompanied the campaign. The King left Saint-Germain on 2 February 1668 to join up with the main army…. as the news of the formation of the Triple Alliance reached him. A spy also whispered in his ear how its members prepare to go to war against France. Insert rage face here.

Nevertheless, Louis moved on with the plan. Condé started the invasion on 4 February and took Besançon on 7 February. On the same day, more French forces under François-Henri de Montmorency, Duc de Luxembourg, managed to take Salin. Both strongholds put up practically no resistance.

The French army then concentrated on taking the town of Dole, which proved to be a bit more difficult. Said town surrendered on 14 February, after a short siege of four days, in which 400–500 French soldiers lost their lives. Five days later, on 19 February, the stronghold of Gray also fell to the French. Louis XIV returned to Saint-Germain afterwards and arrived on 24 February 1668.

After only 17 days, the whole of Franche-Comté was occupied. The reasons for this quick success were surprise, the ill-preparedness of the Spanish and the local population, which tended to sympathise with the French, and mostly welcomed them. Meanwhile, at the southern front of the war, the Spanish made a move and invaded Upper Cerdanya. Now the French defences proved weak.

After the France-Comté was taken to be used as bargaining chip, the Sun King had in mind to take more Spanish controlled lands. He intended to send Turenne on the mission of conquering the remaining parts of the Spanish Netherlands, with 60,000 men, while Monsieur was supposed, with 10,000 men, to advance into Catalonia and Condé, with 22,000 men, supposed to place himself at the border, in order to defend against a possible move by the Holy Roman Empire.

But there was the Triple Alliance and Louis had to consider if France could manage to deal with them all at the same time and Spain on top. Louvois, Turenne and Condé were all pro continuing. For them the situation did not look that bad, since Spain was in a position of weakness. Colbert and foreign minister Hugues de Lionne advised against it. Spain was indeed weak, but, since the Portugal issue was sorted, was now able to draw all forces together and move them against France…. and war, argued Colbert, was expensive. So far it did cost a good 18 million livres already.

The Sun King did a fair bit of pondering and in the end decided to take advantage of the fact that the cards looked still quite good for France. There was the Triple Alliance issue… but that alliance was only there, because Louis and his army did such a great job. He was aware that he most likely could not deal with all of them together and at the same time that they feared he would give it a try. Which in turn somewhat hinted that Louis and France could either by their best friend… or worst enemy.

Thus, Louis XIV announced a cease-fire until the end of March 1668 and began negotiations. In the following April, all nations involved met at Saint-Germain to agree on terms for a peace treaty. Said treaty, known as the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, was signed on May 2.

Louis XIV had to abandon the Franche-Comté, including the free imperial city of Besançon, after destroying all fortifications of the cities of Gray and Dole. The French troops also had to withdraw from the Spanish Netherlands, with a total of 12 conquered cities remaining in their hands: Lille, Tournai, Oudenarde, Courtrai, Furnes, Bergues, Douai with la Scarpe, Binche, Charleroi, Ath and Armentiers.

That doesn’t look too good for Louis, does it? France gained some territory in Flanders, but at the same time had to return most of the Spanish Netherlands and the Franche-Comté into the hands of the Spanish. The Sun King wasn’t happy about that at all. He hoped he could keep all of the Spanish Netherlands and blamed the Dutch for having to return them. But from a military perspective, Louis and France showed everyone what they were able to do and added some strategic points of defence, meaning the cities that could be kept. Those could serve as starting points for future missions….