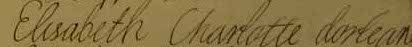

Élisabeth-Charlotte d’Orléans, Duchesse de Lorraine

Born on 13 September in 1676 at Saint-Cloud, Élisabeth-Charlotte was the third and last child born to Philippe de France and his second wife Liselotte von der Pfalz. She was the granddaughter of a King, niece of a King, mother of an Emperor and grandmother of France’s most famous Queen, Marie-Antoinette.

After five years of marriage and two sons, Monsieur was again beside himself with joy as his wife showed signs of another pregnancy. Not just because another baby was on the way, the production of which was not an easy task for him, but also because it meant he had pretty much done his duty and was no longer obligated to share a bed with his wife anymore. Liselotte was not upset about it at all, for she never thought much of the business anyway.

Liselotte was around three months pregnant as their oldest son, Alexandre-Louis, died not yet three years old. Madame was reigned by despair, saying it was the greatest pain ever inflicted on her. She wrote to her half-sister Louise: “I wept six months for my son, so much that I thought I would go crazy (…) it feels like your heart being ripped out of your chest.”

The birth of little Élisabeth-Charlotte tore Madame from despair. Childbirth never went easy for Liselotte and this last birth was especially painful, due to the size of the baby. Madame said the little Princesse was “as fat as a fattened goose and very large for her age” upon her birth.

As a grandchild of a King, the little girl held the rank petite-fille de France, was entitled to be addressed as Royal Highness. As it was custom for royal children, the little girl was not given a name until her baptism and was styled Mademoiselle de Chartres upon her birth.

Mademoiselle de Chartres was baptised together with her older brother, the Duc de Chartres, on 5 October in presence of the King, Queen and most of the court. It was quite the lavish affair followed by a opulent meal and a opera. Madame wrote: “Last Monday, both of my children have been baptised and were given the names of Monsieur and myself, my boy is now called Philippe and my girl Élisabeth-Charlotte. There is one more Liselotte in the world now, may God ensure that she will not be less happy than me, for then she will have little to complain about.”

There was indeed one more Liselotte in the world now. According to Liselotte, this new Liselotte was just like her… including “shitting in her skirts“. She was a wild thing, running, jumping, playing tricks, was stubborn and “rough as a boy“. Monsieur, who always was a doting papa to his children, adored her very much, but had a bit of an issue that she also inherited her mother’s way of being so very frank and constantly saying what she thinks… Élisabeth-Charlotte received a fabulous education and grew up in the various residences of her father along with the Duc de Chartres. She got along quite well with her older sisters, from their father’s first marriage, too.

After her older sisters were married to the King of Spain and Duc de Savoie (Later King of Sicily and then King of Sardinia.), Mademoiselle de Chartres became simply Mademoiselle, the customary style for the oldest unmarried royal princesse.

As such, her marriage was of course a huge thing. Louis XIV himself was without legitimate daughters, thus his nieces took the place. His oldest niece Marie-Louise was married to Charles II of Spain to bind the respective Kingdoms in blood again. Her sister Anne-Marie was married to Savoie, to make it a bit more France-friendly. Élisabeth-Charlotte… well, there were many candidates for many reasons.

Liselotte was very firm in her idea not to ‘sell’ her daughter for less than she was worth and Mademoiselle shared the idea. As the Dauphine suggested Élisabeth-Charlotte should marry her younger brother Joseph-Clemens, Élisabeth-Charlotte drily replied „Je ne suis pas faite, Madame, pour un cadet.“ – “I am not made, Madame, for a younger son.”

A marriage to William III of England, whose wife, Mary II, died in 1694, was briefly considered by Liselotte, but dismissed due to religious differences aka one side was Catholic and the other Protestant. Pope Innocent XII suggested a marriage to Joseph of Habsburg, the heir to Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, to sooth the French-Austrian relationship, but it was dismissed as well.

After the sudden death of the Dauphine in 1690, it was considered to marry Élisabeth-Charlotte to her cousin le Grand Dauphin, but this idea was dismissed as well. Louis XIV had other plans. He wanted Élisabeth-Charlotte to marry his illegitimate son the Duc du Maine, by no means a court-favourite due to his extremely spoiled nature. Madame was shocked as she heard of it. She always had a strong dislike for bastards, especially royal ones, and such a marriage was out of the question for her. The court and Louis XIV still remembered Madame’s outrage, followed by a mighty slap, as she heard her son agreed to the King’s plan to marry Mademoiselle de Blois, a legitimised daughter of Louis XIV. While she had to endure this marriage, Madame was determined not to ‘sell’ her daughter like this as well. It was one thing for a higher ranking man to marry a lower ranking woman, but a different thing for a royal princesse to settle for a lower ranking man and thus be demoted… especially if this man was the result of double-adultery. Madame fought with all she had and won. Louis XIV feared the whole thing would cause too much of a scandal in the end. The Duc du Maine married Louise-Bénédicte de Bourbon instead, against the will of the latter.

In the end, Élisabeth-Charlotte became, to quote her mother, a “victim of war” and it turned out to be a very happy match. Mademoiselle was already in her twenties then and considered to be almost an old maid by some members of the court.

The Treaty of Ryswick was what finally brought a respectable husband for Élisabeth-Charlotte. In the Treaty Louis XIV was forced to return illegally occupied territories to their rightful ruler. It was the sovereign Duchy of Lorraine. The ruler had the fancy name Leopold Joseph Charles Dominique Agapet Hyacinthe de Lorraine and was the oldest son of Charles V and Eleanor of Austria, a half-sister of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I.

At the time of Leopold Joseph’s birth, Lorraine was occupied by Louis XIV and his parents lived in exile at the court of Leopold I. Leopold was born in the palace of Innsbruck, named in honour of the Emperor and grew up in Innsbruck. As his father died in 1690 and Leopold inherited the occupied Duchy, but he did not actually see Lorraine until after the signing of the Treaty in 1697.

Since Louis XIV was a bit paranoid in matters of Habsburg ambitions, and this new Duc de Lorraine grew up among Habsburgs, it was thought to be a good idea to marry him to a French princesse. Lest there might be new hostilities in the future… never minding that they were mostly caused by the French. The Duchy had been ruined by nearly 80 years of wars and various occupations and the indented groom was almost without a penny.

The match was agreed upon at the end of 1697, but it took until October the following year for the wedding to take place. It was a major affair and needed plenty of preparation, which in the end caused the delay because the couple’s residence in Nancy was not yet ready, also the carriages and livrees, and then it was noticed that the young Duc had forgotten to write Rome in order to seek the Pope’s permission for the wedding. A special papal allowance was needed since bride and groom were fourth-cousins. The court resided at Fontainebleau as a rider arrived with the papal letter of permission and since it all took so long, talk had it, the groom, who was not meant to see the bride before the wedding, snuck into court in disguise in the meanwhile to have a glance.

Agreeing on a dowry also took a while. In the end, the result was rather respectable. Louis XIV agreed to give the bride 900.000 livres, one third upon the signing of the contract and the rest within six months of the marriage. Monsieur and Madame added another 200.000 livres in money, which was to be paid after their demise, and 300.000 livres in jewellery and necessary items to be received at once. In turn, Mademoiselle had to give up all rights of inheritance for herself and her children in favour of her brother.

Madame describes Mademoiselle’s trousseau in a letter as it was on display, as custom, for the court: two gem covered wedding gowns, seven state gowns, six elegant house gowns, two simpler house gowns, plenty of chemises with elaborate lace, and linen in which the combined coat of arms of the couple was stitched. She also mentioned what Mademoiselle received as a wedding gift from the young Duc, despite his lack of money: diamond earrings and earhangers, a string of pearls, two bracelets with pearls, a bracelet with a large diamond, and two rings with large white stones. This wedding gift was calculated to be worth 400.000 livres. Mademoiselle loved every piece of it.

What did the bride think of all of it? Apparently she was quite pleased and happy to finally be married. Madame was a bit unsure about the groom in first, due to the lack of money, but later said she was glad her daughter was to marry a rightful Prince with ancestors one does not have to be ashamed of, adding that the groom was handsome and in possession of virtues and many merits. Both Madame and Monsieur were also quite pleased by the fact that their daughter was not married to someone living ‘too far’ away, which meant she could still see her on occasion… but there were not too many people who thought the match would be a happy one.

In fact, some of the Princesses and Duchesses thought the whole affair to be rather degrading for Élisabeth-Charlotte, while at the same time they were jealous in regards of the dowry. Some of them tried to attend the ceremonies dressed in mourning, taking the death of a child of the Duc du Maine as pretext, while the Duchesses were outraged the Lorraine Princesses were given precedence over them. Louis XIV put an end to all of it and the ceremonies went ahead as planned.

On 12 October in 1698, a Sunday, the official engagement ceremony too place at Fontainebleau, after which the King and Dauphin said their private au-revoirs, with plenty of tears, to the bride. The next day, 13 October, the wedding by proxy, with the Duc d’Elbeuf standing in for the Duc de Lorraine, was celebrated. The bride was dressed in a gown of silver with plenty of silver lace and she was embraced by the King, who said his final au-revoir with even more tears. Everyone present remarked on how many tears were wept that day. Monsieur and Madame and their children sat down for a private meal after the ceremony, then boarded a carriage to accompany the bride to Paris. They stayed there, at the Palais-Royal, for two days, before the bride departed for Nancy….with another gift from Louis XIV. As they arrived in Paris, they found a toilet-table of gilded silver and a set of furniture, consisting of a bed, six armchairs, twenty-four chairs and a tablecloth of matching fabric, worth 40.000 livres, waiting for the bride. Madame remarked in a letter that Lorraine won’t find her daughter equipped badly, most likely remembering her own embarrassment over her very meager trousseau.

The final scene of parting of the family took place in private, in order to spare them all from the public gaze in such a sad and yet happy moment. Monsieur, Madame and the Duc de Chartres went to the new Duchesse de Lorraine as she was still in bed. They did not stay for long and left again after a few embraces and soft words to return to Fontainebleu.

The final scene of parting of the family took place in private, in order to spare them all from the public gaze in such a sad and yet happy moment. Monsieur, Madame and the Duc de Chartres went to the new Duchesse de Lorraine as she was still in bed. They did not stay for long and left again after a few embraces and soft words to return to Fontainebleu.

The new Duchesse boarded her carriage a bit later and went en route to Bar-le-Duc, where her husband was awaiting her. Thanks to Madame, we have some details on the first night the couple spent together… as well as the Duc’s Leopold. (Gotta love Liselotte.) She writes to Sophie of Hannover about a letter she received from the Duchesse to inform her that they are supposed to spent their first night together and comments that her daughter is about to really leave the King’s house and enter that of Lorraine, as she is supposed to become a women this very day, and that she will most likely find it a strange matter. One hears all sort of things about the groom, writes Madame, one thing is that once as he was bathed, the person attending him asked the Duc to lift his arm in order to be washed… but the arm was not actually a arm. Madame closes by uttering her curiosity to know how this first night went.

It went very well according to Élisabeth-Charlotte. Mother and daughter exchanged plenty of letters, Madame wrote on Monday, Thursday and Saturday, and Élisabeth-Charlotte was not all blushing at the thought of writing to her mother in regards of the activities of her husband’s Leopold. Madame mentions that Élisabeth-Charlotte seems to be quite pleased with the husband’s Leopold and finds the matter not as bothersome as Madame herself, which is a bit strange to Madame. Élisabeth-Charlotte also wrote her mother about how she had to change garments, for the gown she wore was so heavy that she could not walk in it, and that as she was undressed and just about to be dressed again, her husband entered. The sight of her stirred Leopold’s Leopold and things happened….

…things happened quite often… and Élisabeth-Charlotte soon became pregnant. Her mother provided her with all sort of advice in letters and the Duchesse loved the idea of mother and father being present for the birth. A voyage was arranged… and cancelled last minute, because of issues regarding the seating arrangement. Leopold wished to be seated on an armchair in presence of Monsieur and Madame. Louis XIV disagreed. Nobody wanted to give in. Élisabeth-Charlotte gave birth to a son on 26 August in 1699. He was named Leopold after his father and much adored by both of them. Madame writes of fears that her daughter will spoil the baby to much, for she has been told the Duchesse insists on having him around all day and kisses him all the time. In regards of the Duc she writes that he pretends not to be too interested, as it is considered proper for a father, but in private he is covering his son with kisses as well. Unfortunately, little Leopold died only a few months later.

The family was reunited again the following year at Versailles as Leopold had to pay homage to Louis XIV. Monsieur and Madame got to know their son-in-law and found him good enough. The court was surprised by it all. Duc and Duchesse appeared to be truly happy with each other… which also was a bit surprising to Madame. Élisabeth-Charlotte wrote her often that she loved her husband and was very much loved in return, but Madame could not quite believe it until she saw it.

In order to avoid ado about etiquette, seating arrangements and to lower the costs of the trip, it was decided the Duc should travel incognito under the name Monsieur de Pont-á-Mousson. Monsieur agreed to host the couple at the Palais-Royal and cover all expenses of the stay. They enjoyed the opera together and had a private meal, then Monsieur accompanied Monsieur de Pont-á-Mousson to Versailles, where the King left his council meeting to greet him. Unfortunately, the voyage did not end as well as it started. One the day her husband met the King, Élisabeth-Charlotte had to remain in bed with what turned out to be smallpox. Madame locked herself in with her daughter, forbade everyone who did not yet have smallpox to enter, and nursed her back to health. It took fourteen days of motherly care and constant reminders not to scratch herself until Élisabeth-Charlotte recovered without one single pockmark.

The couple returned to Lorraine and Élisabeth-Charlotte got pregnant with their second child. She gave birth to a daughter, named Élisabeth-Charlotte after her, in October 1700. And pretty much as soon as she had recovered from childbirth, she became pregnant again. All was well. Until June 1701, as the news of her father’s sudden dead reached the pregnant Élisabeth-Charlotte. Her brother was now the new Duc d’Orléans and their mother sought permission to move to Lorraine. Louis XIV did not grant it and also forbade the widowed Madame to set foot on foreign soil, which limited her to only see her daughter when the Duc and Duchesse visited Versailles. Élisabeth-Charlotte did not like that one bit, but what was she supposed to do?

And then it got even worse. The Duchesse gave birth to their third child, Louise-Christine, in November 1701 and was again pregnant as the War of the Spanish Succession swept over Europe and tore the relationship of the Duc de Lorraine and the Sun King into pieces.

Louis XIV sent troops to Lorraine and occupied the Duchy once more. The Duc and Duchesse, in the last stages of pregnancy, had to flee Nancy for their château at Lunéville. She gave birth to a daughter, Marie-Gabrièle-Charlotte, a couple of days later. The Duc busied himself with renovations of the chateau and did it so well, that the palace was soon nicknamed the Versailles of Lorraine. Élisabeth-Charlotte, in the meanwhile, was pregnant again and gave birth to a boy, Louis, at the beginning of 1704. It was their fifth child and all the pregnancies started to take their toll. The Duchesse got rounder and rounder….like her mother. The dominating topic of conversation between mother and daughter at this time appears to be childcare. Élisabeth-Charlotte took into mind to care for her children herself, instead of leaving it, as it was proper, to a governess. Liselotte was quite astonished in regards of her daughter’s desires and wrote she doubts Élisabeth-Charlotte has enough patience to deal all day with small children, but that she, as the mother, surely knows what is best for them… and if she gets fed up with it, a governess can still be appointed.

In 1708, three pregnancies later, the Duc de Lorraine fell in love with a other woman. It was Anne-Marguerite de Ligniville and she was ten years younger than Élisabeth-Charlotte. The Duchesse, of course, did not enjoy to be replaced by someone else in her husband’s heart. She wrote her mother about it and her embarrassment and Liselotte advised to endure it with noble taciturnity. She did just that. From then on Élisabeth-Charlotte, Anne-Marguerite and Leopold lived together until the demise of the latter. Leopold having a mistress did not prevent him from visiting his wife’s bedchamber however. He did so regularly and with great enthusiasm, which led to six more pregnancies.

So, Élisabeth-Charlotte was in the years between 1698 and 1715 either pregnant or just recovering from childbirth. Only four of their fourteen children reached adulthood. Their first-born child Leopold died not yet aged one. Their second, fourth and fifth child all died within the same week in 1711 of smallpox. Their third born child died not even a month after the birth. Their sixth child was three years old as it died. Their seventh child was four years. Their tenth child lived only two months and their last child was stillborn.

Thus, of fourteen children born, Élisabeth-Charlotte was left with only five still living in 1715 as the great Sun King died and her brother became Regent of France. Her oldest living son, Léopold-Clément, died aged sixteen in 1723.

The Duchesse was desperate whenever one of her children died. The pox epidemic of 1711 during which three of her children died in one week, left her in utter despair. Unfortunately, the correspondence of mother and daughter was lost during a fire at the château de Lunéville in 1719, but we know from Liselotte’s letters to others that Élisabeth-Charlotte wrote her mother of her wish to die, saying can not stand the suffering any longer and wishes to be reunited with all the children she had lost to that point and her doting papa.

Mother and daughter were briefly reunited during a visit to court in 1718… eighteen years after they had last seen each other. This visit lasted from February to April and the Duc once again travelled incognito to Paris, but in the same carriage as his wife, his mistress, who was a dame d’honneur to the Duchesse, and the husband of said mistress. Both the Duchesse and the husband of the mistress apparently ignored the whole thing so well, that they, meaning both married couples, lived in perfect harmony. They all lived in the Palais-Royal during the visit and enjoyed a row of balls, suppers, hunts, games and operas together.

What Élisabeth-Charlotte could not ignore was the obvious decline in manners and etiquette that happened since her last visit. Madame writes that she and her daughter often visited the opera together in order to have a private chat about topics they could not discuss via letter and that the Duchesse was shocked to see how married females of good names threw themselves at gentlemen in public as if it was the most normal thing on earth. The Duc promised Madame upon their departure to visit again in two years time… but that did not happen. As fertile as he was, his mistress was in different circumstances all the time and it prevented travelling. Thus it took until 1722 until Lorraine visited France again, this time for the coronation of Louis XV… just in time. It was the last time Élisabeth-Charlotte saw her mother and brother.

Élisabeth-Charlotte, Leopold and their at this point five still living children all travelled to Rheims, where they met Madame on 22 October. The Duchesse knew from the letters of her mother that Madame was feeling quite unwell recently, but Élisabeth-Charlotte did not take it too serious. Madame had a habit of complaining about her health. Seeing her in person, Élisabeth-Charlotte was shocked about the state her mother was in and wept desperate tears for hours. Leopold made himself sparse. He travelled incognito again and happened to suffer of a royale. Fearing he might upset the Emperor, he only stayed long enough to say bonjour to Madame, who had scolded him in matters of mistress recently, and to remind the Regent that he owed him money.

This visit lasted only a few days and ended with plenty of tears. The Duc and Duchesse returned to Lorraine, Madame to Saint-Cloud, where she died a couple of weeks later, on 8 December in 1722. Not yet a year later, the Duchesse also lost her brother. Philippe died on 2 December in 1723. So, mourning for her mother was followed for mourning for her son and for her brother. Élisabeth-Charlotte now had two boys and two girls left and her then oldest son François-Étienne was sent to Vienna in order to be educated. What to do? Engage in the fine arts.

Élisabeth-Charlotte became a patron for various artists, promoted music and the opera and the theatre. But festivities became quite rare. Leopold was not in the best health, recovered again, just to fall ill again. He made his will and excluded his wife from a possible regency council. François-Étienne was still in Vienna to be educated as Leopold died on 27 March in 1729. The next morning, Élisabeth-Charlotte was declared Regent of Lorraine for her absent son.

The twenty year old François-Étienne preferred Austria over Lorraine and did not set foot into his Duchy until eight months later. In the meanwhile, Élisabeth-Charlotte did her very best to bring the Duchy’s finances back in order. As François-Étienne finally arrived, he was considered to be more foreigner than anything else.

François-Étienne left Lorraine again in 1731 and Élisabeth-Charlotte became once more Regent of the Duchy as her son travelled on behest of the Emperor. Then the Polish War of Succession happened…

Despite Élisabeth-Charlotte’s protests, Lorraine was once again occupied by French troops. She did her very best to spare the people of Lorraine from any inconvenience during the occupation and in the end the Duchy was lost. As part of the Polish War of Succession, her son exchanged Lorraine for the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. The Duchesse warned her son not to renounce his rights or exchange the Duchy for a other, but he did not listen.

Lorraine went to Stanisław Leszczyński, the father-in-law of Louis XV and dethroned Polish King. The Duchesse was furious with her son and vowed not to leave Lorraine… even after François-Étienne married Maria-Theresia of Austria and became thus the heir of the Holy Roman Emperor.

The Duchesse without Duchy hoped she would be able to remain in Lunéville, but Stanisław wanted it as residence. So, she had to pack her things and was relocated to Château d’Haroué by Commercy, which was erected into a sovereign principality by Louis XV for her to reign over during her dowager years. The departure of Élisabeth-Charlotte and her two daughters from Lunéville in March 1737 was a tragic affair. Mother and daughters bemoaned what had happened, cursed it, wept desperately, sure never to see their lands again, and clung to each other. All the while, their desperation was shared by the people of Lorraine who tried to delay and prevent their departure by disturbing the carriages by walking in front of them or lined the streets with tears running down their cheeks.

The Duchesse de Lorraine became the Princesse de Commercy and surrounded herself with all those who remained faithful to the ‘old’ rulers of Lorraine, but also tried to function as neutral voice between Lorraine, France and the Empire. Élisabeth-Charlotte spent the last years of her life more or less happy in Commercy.

In 1743, she had a fit of apoplexy, but recovered. She suffered another fit of apoplexy on around 18 December in 1744, and yet another on 22 December after which she lost consciousness and fell into a coma.

At eight o’clock on the morning of the 23rd December in 1744, Élisabeth-Charlotte d’Orléans breathed her last breath surrounded by faithful Lorraines, who already served her husband before her. Lunéville only mourned a month for her and Commercy went to Stanisław Leszczyński, who made it one of his finest residences. Élisabeth-Charlotte outlived all but three of her fourteen children. Nine months after her death, François-Étienne became Holy Roman Emperor. He was the father of the last Queen of France, Marie-Antoinette.

One Comment

Daryal Savoie

My distant ancestors