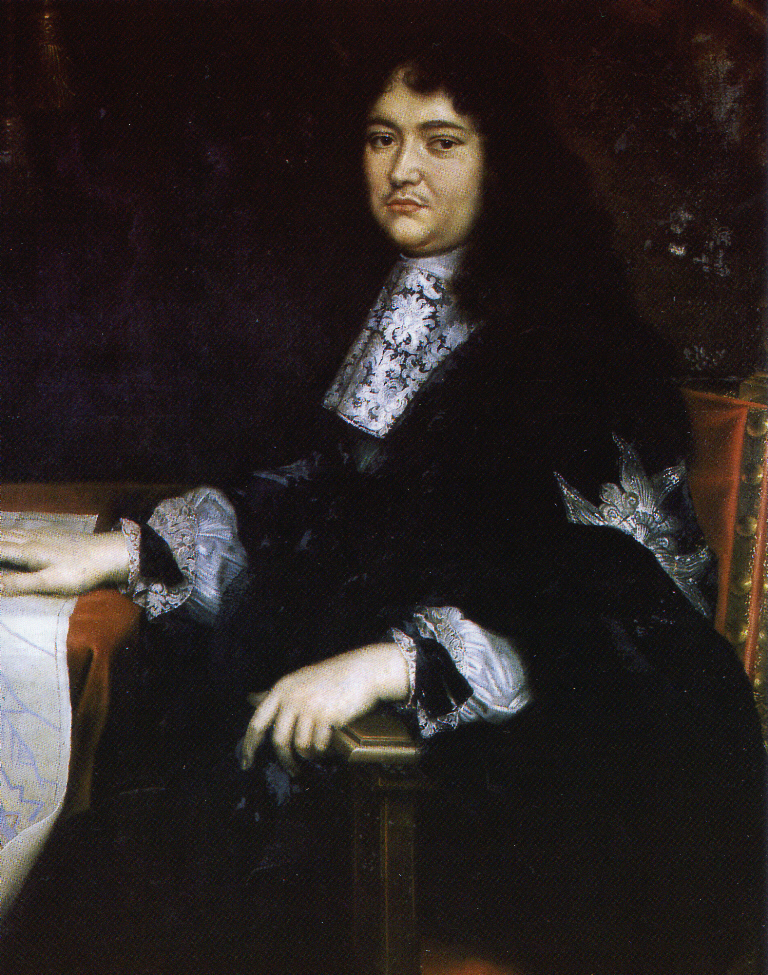

Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, Vicomte de Turenne

“A General who has never been defeated can’t have been at his business very long.” Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, or simply Turenne, is one of the most celebrated war heroes of France and already was one during his lifetime.

Henri comes from a prominent family with Huguenot roots that gained political influence. Henri IV arranged for Turenne’s father to marry Charlotte de La Marck, heiress to the Duchy of Bouillon and of the Principality of Sedan. She died in 1594 in child-bed. With the demise of Charlotte, the Duchy of Bouillon and the Principality of Sedan went to her husband. Both of them were so-called terres souveraines, which meant Turenne’s father became a Prince étranger. After the death of Charlotte, he married Élisabeth de Nassau, a daughter of William the Silent, with whom he had eight children. Turenne was youngest of them and their second son.

Turenne was born on September 11 in 1611 at the Château de Sedan and grew up in the shadow of his big brother, who would one day inherit their father’s titles. Turenne received the usual noble-boy education, but had quite some troubles with that. While his brother was much like his father, robust and extroverted, he was a sickly child, with physical infirmities, and apparently did not learn to speak until he was four years old. The latter caused an impediment of speech, which he never got rid off. Yet he had quite the interest for history and geography, and a special admiration of the exploits of Alexander the Great and Caesar. His slow learning progress and short memory, often frustrated his tutor and father alike.

As Turenne was in his teens, he decided to do something about his not so great physical condition and began to train. After his father’s death in 1623, he devoted himself to bodily exercises and became an excellent rider.

Aged fourteen, Turenne was sent to learn about war under the command of his uncle Maurice of Nassau, Stadtholder of Holland and Prince of Orange. He served as a private soldier in the Eighty Years’ War. In first only as Musketeer, but it turned out that Turenne was more skilled with swords than books and he was promoted to captain of a company of infantry. After five years in Holland, Henri returned to France and following the wishes of his mother, who wanted to show the loyalty of the Bouillon dominions to the French crown, Turenne went to Paris.

By then, Turenne was already a celebrated soldier and famous among the Dutch soldiers. He put that skill into the service of France and impressed Cardinal Richelieu quite a bit. Richelieu thus made him colonel of an infantry regiment. The first time Turenne fought under the French flag was at the siege of La Mothe in Lorraine, under command of Jacques Nompar de Caumont. His great courage at once brought him the promotion to maréchal de camp. Over the course of the next years, Turenne had the chance to impress even more. He participated in various sieges and battles, gaining a reputation as great and brave soldier. In 1636, however, Turenne was badly wounded by the siege of Saverne, but that did not stop him for long. The following year, he was back on the battlefield and another promotion followed. He was made Lieutenant-général and fought under Henri de Lorraine at the Italian campaign of 1639–1640.

Another promotion followed on December 19 in 1643, when Turenne entered the respected rows of the Maréchaux de France, a military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. Turenne was thirty-two by then and learned from four of the most famous commanders. The methodical thinking Prince of Orange, the more fiery Bernhard, the soldiery Cardinal de la Valette and the quite stubborn and astute Henri de Lorraine. Each of them shared their knowledge and their way of handling situations with Turenne and provided him with an education in military matters that was quite unique.

In the following campaigns of the Thirty Years War, Turenne got into closer contact with the Duc d’Enghien, who later went into the annals of history as le Grand Condé…. and then the Fronde happened. The Duc d’Enghien, who in the meanwhile became Prince de Condé, the Senior of the Princes of France, turned against the crown.. and Turenne, maybe persuaded by his love interest Madame de Longueville, who happened to be Condè’s sister, involved himself in the mess as well. But in contrary to the Condès, Turenne thought the whole thing through again and reconciled with the Queen Regent, returning to Paris in May 1651.

As Condé again raised the standard of revolt in the south of France, Turenne met him on the battlefield leading the royal troops. Turenne showed his skills off at Jargeau on March 28, at Gien on April 7, and he practically crushed the civil war in the Battle of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine on July 2 and during the re-occupation of Paris on October 21. The latter granted him a pardon from Louis XIV. During the next years Turenne fought many battles in the name of the King, against the last of the Frondeurs and afterwards the Spanish, until the Treaty of the Pyrenees, signed on 7 November 1659, put an end to the war between Spain and France.

It was the first time in long years, that France was not directly involved in a war… and what does a famed soldier do in times of peace? He enjoys court life… or not so much. Turenne did not quite like the fuss that much. He was much liked by the King, but did not really have a mind for all the ado of the court. Turenne was married to Charlotte de Caumont, a daughter of the Marshal de la Force, since 1652. A bride he chose himself. In 1639, Cardinal Richelieu suggested Turenne should marry one of his nieces, but the offer was politely declined, because the suggested bride was a Catholic. For the same reason an offer of Mazarin to marry one of the Mazarinettes was declined too. The lady Turenne married in the end, was a Protestant like him.

Something else Turenne politely declined was a offer/present from the King. After Mazarin‘s death and Louis XIV’s taking of power, one of the first acts of the King was to make Turenne marshal-general of the camps and armies of the King. Louis XIV actually had in mind to revive the office of Constable of France for Turenne, but for that Turenne would need to become Catholic… thus Turenne declined. Being educated in the Protestant spirit, it was out of the question in first… however some years later, Turenne, who disliked the hostility between the two faiths, began to consider to become Catholic. Two years after his wife died, in 1666, he converted.

By 1667, Turenne was back on the battlefields. He commanded, nominally under Louis XIV, parts of the royal army and took city after city. The War of Devolution did only last for a year, but by its end Louis XIV already had plans for the next one. This Franco-Dutch war was the last for Turenne.

In 1672 Turenne accompanied the army commanded by the King, which overran the Dutch United Provinces up to the gates of Amsterdam. The Dutch opened the dikes and flooded the countryside around Amsterdam, in order to protect the city from the French. This measure completely shocked Turenne, whom the King had left in command. News of this event roused Europe to action, and the conflict spread to Germany and Turenne fought a successful war of manoeuvre on the middle Rhine. In January 1673 Turenne pushed deep into Germany and forced the Elector of Brandenburg to make peace… but later on, Turenne had to withdraw from the area.

June 1674, looked a bit better again. Turenne won the battle of Sinzheim, which made him master of the Electorate of the Palatinate. As such, he took advantage of the Palatine and much of the area was destroyed. A dark spot on Turenne’s white waistcoat. In the autumn the anti-French allies again advanced, and though they again out-manoeuvred Turenne, the action of the neutral city of Strasbourg occasioned his failure by permitting the enemy to cross the Rhine via a bridge. The following Battle of Enzheim was a tactical victory, but hardly affected the situation, for the enemy stood in Alsace.

Turenne sought to change that by going on a rather risky campaign. He marched troops in the middle of the winter and took the enemy by surprise, driving them back to where they came from. He defeated them at Turkheim… and as revenge for the active resistance the inhabitants of the city, Turenne let his troops loot it and massacre the remaining population during two weeks. Another dark spot on Turenne’s white waistcoat.

In the following summer campaign on 27 July 1675, at the Battle of Salzbach, Turenne was killed by one of the first shots fired. Around two o’clock in the afternoon that day, Pierre de Mormez, Seigneur de Saint Hilaire, Turenne’s lieutenant-general of artillery, asked him to inspect a battery. According to one source, Turenne agreed to be cautious, reportedly saying “je ne veux point etre tue aujourd’hui“- “I do not want to be killed today.” As both men, Pierre de Mormez apparently wore a bright red coat, had a look at the battery an Imperial cannonball hit them. It tore off Pierre de Mormez’s left arm and passed straight through Turenne’s body, from shoulder to side. Turenne then apparently made two steps forward and fell. Pierre de Mormez survived, Turenne not.

Turenne’s body was brought to Paris and Louis XIV granted him the great honour to be buried among the King’s of France at Saint-Denis. His grave, like the others, was opened during the French Revolution, but Turenne was so universally respected that he did not share the fate of the King’s, Queens, Princes and Princesses buried there. Turenne’s body was found in a good condition and instead of being tossed into a mass grave, he was put on display for several months…. and his teeth were sold as souvenirs. His body was then brought to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris and afterwards to the Musée des Monuments Français. After the end of the French Revolution, Napoleon ordered Turenne’s body to be brought to the Hôtel des Invalides, where it was buried again with military glories.