The death of Louis XIII

Louis XIII’s reign as King of France lasted exactly 33 years. His Kingship was not an easy one. He lost his father, Henri IV, early and was in constant disagreement with his mother, Marie de Médicis, about what was the best for France and she even went to a proper war with him at one point. Louis le Juste had problems to produce an heir, had to deal with plenty of intrigues, an unruly brother, a seemingly never ending war in Europe and to face people saying he was a weak King.

Louis XIII‘s health was never stable, something he had in common with his Prime Minister, Cardinal de Richelieu. The Cardinal often suffered of fevers and headaches, by the end of November 1642 he started to cough blood. The doctors attempted to prolong his life by regular blood-letting, which of course weakened him only further, and so it was no surprise to anyone as, on 4 December 1642, the death of the great Cardinal de Richelieu was announced. Shortly later, in spring of 1643, as the first flowers began to grow, the health of Louis XIII declined rapidly. By the end of March it was clear to Louis XIII that he had not much time left on this earth. “I see from your silence that I am going to die. God knows I never liked life and that I shall be overjoyed to go to Him” he said to his physician Monsieur Bouvard and busied himself, with all the strength that he had left, to make arrangement of what was to come after.

His heir was a little boy, which meant the Kingdom was to be ruled by a Regent until his son was of age… and since his son was still so young, there was a long Regency to come. Who to pick as Regent?

Louis did not trust his wife to be up to the task, but according to tradition she would become the Regent of France, no matter if he wanted it or not. Thus Louis sought to limited her power as Regent by setting up a Regency Council. This way, Anne d’Autriche could not decide anything herself, but all matters would have been decided by vote during a meeting of the Council. It was what this old King thought to be best for the new King and the kingdom he would inherit. But why the distrust in Anne?

It was a result of quarrels and what Louis thought to be a betrayal. As Anne came to the French court, she had quite the hard time. She was young and hardly spoke French. The French customs were strange to her. She had problems with the French etiquette, although it was a bit more lax compared to the Spanish. In Spain, for example, the Queen’s foot was a sacred object that nobody was allowed to touch. People in France thought that quite strange. Anne secluded herself more and more from the court, which did not really seem to care for her… no wonder, since the old Queen of France, Marie de Médicis, still styled herself in the same manner as if she was the current Queen. Thus Anne surrounded herself with Spanish ladies, spoke Spanish all day, which of course did not help to improve her French and led to more awkward moments of not understanding or not knowing what to say with her husband’s family. Anne continued to dress in Spanish fashion too, which the French ladies could not understand at all. It took years and the intervening of the Duc de Luynes, a friend of Louis XIII, to make Anne more French.

Anne’s Spanish ladies were replaced with French ladies, which forced her to learn the language, and her new French ladies encouraged her to try out the French fashion, which was way less boring and prudish compared to the gowns of Spanish fashion she still wore. So far so good, Louis was pleased with all of that. Anne then won a French confidant in form of the wife of the Duc de Luynes… and that proved to be a problem. Madame de Luynes was by all means to fond of intrigue and Anne was in the midst of it. The King blamed Madame de Luynes for Anne’s miscarriage in 1622, because she did not take good enough care of the Queen. The Duc de Luynes tried to calm the situation, but then died. Madame de Luynes married her lover in a swift and became the infamous Madame de Chevreuse. More intrigues followed. Anne sided with Madame de Chevreuse against Cardinal de Richelieu, which Louis did not like at all. In company of ladies like Madame de Chevreuse, Anne also started to, unwillingly as it appears, attract one or two admirers. Louis did not like that either. Something that was a cause of great stress between King and Queen was the following affaire Buckingham.

Charles I of England married Louis’ sister Henriette-Marie in 1625. The Duke of Buckingham, Charles’ favourite, was sent to France and apparently fell in love with Anne. He was charged with escorting Henriette-Marie to England and as it was custom, the French court accompanied the bride to the border. Louis stayed in Paris, but Anne and the Queen Mother joined the bride for the voyage. As Amiens was reached, on 14 June, the advances Buckingham made towards Anne led Madame de Chevreuse to arrange a secret meeting between them in a secluded garden….Nobody is quite sure what happened that night. According to Pierre de la Porte, Anne’s valet de chambre, the Duke’s advances reached a new height and Anne was heard to utter a cry. According to the Historiettes of Tallemant des Reaux, Buckingham tried to force himself upon Anne and while doing that scratched her thighs. Whatever happened, talk of it circulated through all of France and Europe. Some putting the blame on Buckingham and others saying Anne was to blame. Louis XIII was very angry and forbade Buckingham to set foot on French soil again.

And all of that, the intrigues and supposed lovers, were not even the worst of it. Anne’s brother, who was married to Louis’ sister Élisabeth, succeeded to the crown of Spain as Philip IV in 1621. Of course, Anne was in contact with the Spanish side of the family. After all, she had pretty much raised her younger siblings like a mother would, as their own mother died young and sudden. But Louis and the Cardinal had their issues with Spain and then the Cardinal gave Anne more reason to have issues with him. At that time, one plot followed the next and many of them were aimed at Louis XIII and Richelieu with the aim of removing either one or both of them from power. Richelieu placed Madeleine du Fargis among Anne’s ladies. She was supposed to spy on her for him… but instead she became Anne’s favourite. In the meanwhile, the Queen Mother Marie de Médicis, who was not happy to have lost her influence over Louis, and the King’s brother Gaston de France were up to their necks in plots as well. Anne is said to have cooperated with them in one of those plots and as punishment Louis removed a lot of her favourite ladies in December 1630. Madame du Fargis was one of them. She fled to Brussels and letters were discovered in which was hinted that Anne was not opposed to marry Gaston should Louis XIII be removed from the throne…. Louis was again, of course, rather furious.

Anne was questioned about the letters, confirmed the writing was that of Madame du Fargis, but denied any knowledge or approval of marriage talk between her and Gaston. Louis somewhat forgave her for that one. France declared war on Spain in 1635. Anne entertained a secret exchange of letters with her brother Philip IV as well as with Spanish ambassador and the governor of the Spanish Netherlands. The correspondence was exchanged with the help of Anne’s valet Monsieur de La Porte and the Mesdames de Chevreuse and du Fargis. Some of the letters were of a rather delicate nature, for Anne made inquires in them which could be seen as her trying to get involved in support of Spain. Not good at all. Cardinal de Richelieu, who always had a close eye on Anne, got suspicious and ordered an investigation in regards of how close the contact between the Queen of France and her Spanish relatives was. The Cardinal picked the right people to be questioned and they admitted to have forwarded secret letters. Anne was thus called to be questioned. She denied that such things ever happened… but as the pressure got too much a couple of days later, she admitted it all. Poor Anne was forced to sign a paper that opened her letters for inspection, meaning the Cardinal would read everything she wrote before it could be sent, she was forbidden to visit convents, what she often did, without first getting permission and was not allowed to be left unattended, meaning someone always had to be with her. Furthermore, pretty much all of her household was replaced with people loyal to King and Cardinal, who would of course report her every move.

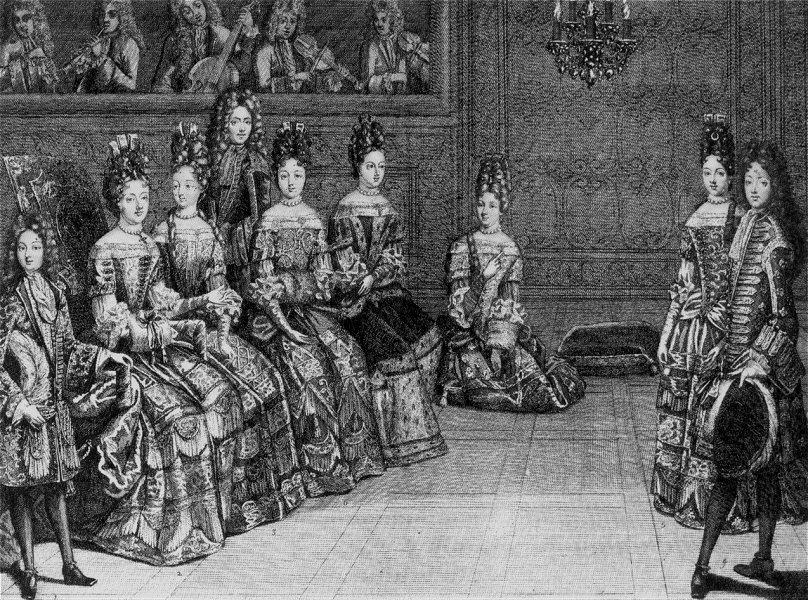

From that point on, Louis never really trusted Anne again. He did not trust her to be a good wife, or to be a good mother, or to be the Regent of a whole Kingdom….but now Louis was in the woes of death and at the same time, the official baptism of Monseigneur le Dauphin was prepared. On 20 April 1643 Louis XIII announced that a Regency Council will rule France after his demise. It was made official the following day by the Parlement de Paris. The same day, 21 April 1643, the court gathered in the chapel of Saint-Germain-en-Laye to celebrate the baptism of their future King.

Meanwhile, in a different part of the venerable château, Louis XIII laid dying. The King was too weak to take part in the baptism ceremony, the death watch had already begun and Louis sought peace in prayers, which were said non-stop in his chamber. The atmosphere was sombre. As Madame de Motteville put it, the King “was dying every day without being able to finish dying.” An anecdote, of which nobody can say if true or not, tells us that Louis XIII summoned his son to his dying chamber shortly after the baptism ceremony to ask: “What is your name now, my son?” The Dauphin, still full of pride at having done so extraordinary well during the ceremony, replied “Louis XIV, father.” Louis XIII smiled briefly. “Not yet, not yet, but you may be soon, if such is the will of God.” The health of the old King made a turn for the worse on the following day.

He was in such a bad state, that it was believed he would not see the end of the day. Louis XIII asked for his children to be brought to him. He was merely skin and bones, his long face pale, and his hands like those of a skeleton. Anne d’Autriche accompanied both children to the bedside of their dying father. Philippe, then the Duc d’Anjou, was still too young to grasp what was going on. He must have sensed something bad was about to happen, but being still pretty much a toddler he seems to have been kept out of side most of the time. This day, both of them were made to kneel by the bed of their father and received the fatherly blessing by a trembling skeleton hand. It is not hard to imagine, that both were probably terrified by the whole thing. Philippe probably even more so than Louis.

Although it was not expected, the King saw the end of the day and lived for another two weeks. On 12 May, Louis XIII asked to see his children again to say his farewell. Again, Louis and Philippe were brought to him and his skeleton hand fondled their pretty heads. This and the words his father spoke, “Children, I pray God to bless you and have you in His holy keeping“, sent Louis in a state of violent tears. The children were quickly removed from the room, in order not to disturb the King with their sobbing.

What happened the following day, 13 May, got Madame de Lansac so worried that she refused, out of fear, to leave the Dauphin alone for a second. The Dauphin was brought to his father again and told by Monsieur Dubois to behold the King, who was lying motionless in his bed, more dead than alive, a sight truly disturbing, so the Dauphin may remember him when he had reached adulthood. Louis did so and after he had looked at his father for a good while, was too moved by it to remain any longer in the room. The Dauphin, who would be King in less than a day, went out into the corridor and there encountered a valet. Said valet tactlessly asked Louis that if his dear father, the King, was to die now if he then would like to be King. The Dauphin burst into tears and reportedly replied: “No, I do not want to be King. If he dies, I will throw myself into the moat.“

After weeks in the grasp of Death, which seemingly refused to take the final step, Louis XIII became delirious on 14 May. It was the 33rd anniversary of the assassination of le Bon Roi Henri, his father, who had struggled so much all his life and overcame any obstacle put in his way. Louis le Juste began to hallucinate and call for his sword, as he suddenly exhaled long and slow. Anne was at the side of her husband as he took his last breath and wept bitter tears. Le Roi est mort. The last breath of the old King marked the rise of the new. Monseigneur le Dauphin, Louis-Dieudonné, was now Louis XIV. A King not yet five years of age. His brother, the little Duc d’Anjou, not yet three years old, became Monsieur, the traditional form of address for the King’s brother, though he was commonly called le Petit Monsieur in order not to confuse him with Gaston, the brother of the old King and their uncle. Anne d’Autriche left the body of her husband in the care of the officials appointed to prepare it for the Lying in State. With swift feet, she hurried to the rooms of her son, who was now also her King, and kneeled before him. Both embraced and wept together. Vive le Roi!

As it is always at such occasions, no matter if of a happy or sad nature, the room quickly filled with curious courtiers. They all wanted to see their new King, this weeping little boy. Anne could not take the noise and all they eyes watching the every move of her son. The Duc de Beaufort, cousin to the new King, to was ordered to send all those curious eyes away. Among them was also the Prince de Condé, also a cousin to the new King, and the Prince did not at all like to be told to leave the room at once. Thus, not yet and hour after the death of Louis XIII, Beaufort and Condé nearly ended up in violent quarrel in front of their new King. Anne d’Autriche had already made her mind up to leave Saint-Germain as quickly as possible to travel the few kilometres to Paris with her sons. The people ought to see their King. Anne knew that at this very moment, it was important to draw the people to their Boy-King. They needed to see him, to see how perfect he was, to see that he will mean a bright future for them all. Her own position was far from stable. At any given moment, people opposed to her could strike and take her children away. They could place the King under the guidance of someone else, form him to their will. The Regency Council could do it as well. The transition from King to King, always came with a flood of intrigues by people who either wanted to keep their positions or gain new and better position. It would be the same this time. A new King meant a new France.

Saint-Germain, the childhood-home of the new King, was pretty much deserted by the very next day. Only the body of Louis XIII remained there, along with some people to watch over the deceased King. As Madame de Motteville reports, those that came to behold it, the ones that did not flock to Paris to watch the entry of the new King into his capital, did so more out of curiosity than affection.

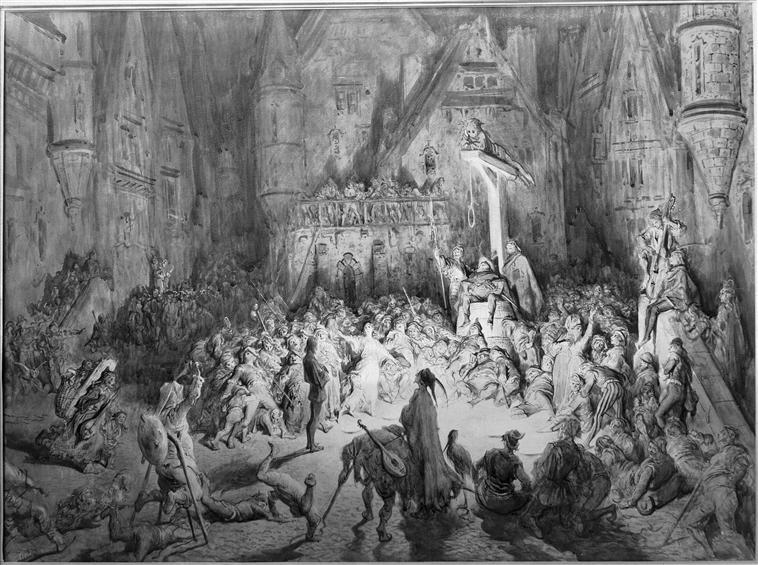

Not yet five years old and not yet King for a whole day, Louis XIV made his entry into Paris the following day. It was sombre and joyful at the same time. Under shouts of Vive le Roi!, the Musketeer flanked royal carriage rolled into Paris. It was drawn by six strong horses and inside, sat the King, his brother, their mother, their uncle the Duc d’Orléans and their cousin the Prince de Condé. Monsieur le Grand, the Grand Écuyer de France, rode to the right of the carriage with the Royal Sword and behind it, followed a procession of carriages and riders. Princes, Ducs, soldiers and guards. They all followed their new King into the city. Paris had not seen such a spectacle for quite a while and the streets where filled with people, from commoners, to members of the bourgeoisie, to envoys from foreign lands and on the balconies of the great hôtels, the ladies gathered and whispered to each other. It was the dawn of a new era, that of the Sun King.

2 Comments

Eva Veverka

Who was Monsieur le Grand, the Grand Ecuyer de France?

Their cousin the Prince de Conde, was he Gastn’s son? (Gaston always bugs me in every story you post.)

Aurora

The Grand Ecuyer de France at that time was Henri de Lorraine, the father of the Chevalier de Lorraine. The Condè’s are a branch of the Bourbon family, but not Gaston’s son. Gaston only had one son and he died young.