Marie-Madeleine-Marguerite d’Aubray, Marquise de Brinvilliers

Marie-Madeleine Marguerite d’Aubray was born on July 2 in 1630, into a wealthy and well-known noble family. Her father, Antoine Dreux d’Aubray, was a civil lieutenant of the Châtelet during the Fronde. Her mother died in childbirth and, according to reports, Marie Madeleine was sexually abused by three servants as she was seven, then had a incestuous relationship with one of her brothers at the age of ten.

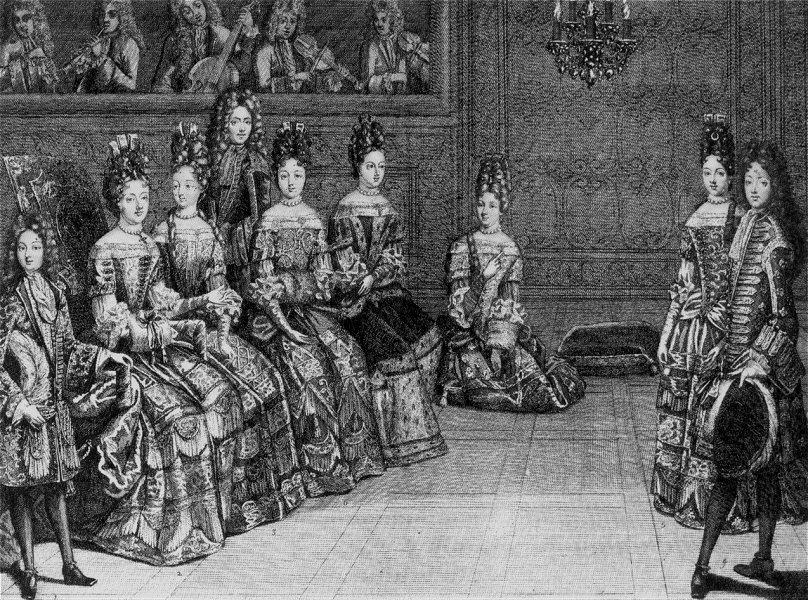

On December 21 in 1651, as she was twenty-one years old, Marie-Madeleine married Antoine Gobelin, the Marquis de Brinvilliers. Marie-Madeleine brought two hundred thousand livres into the marriage with the Marquis. He himself was not poor either, being the commanding officer of the régiment d’Auvergne. Yet their wealth did not last long, the Marquis was a bit of a gambler and a spendthrift. Her husband allowed Marie-Madeleine certain freedoms not every husband would be fine with, one of those was her having lovers. The Marquis himself was not innocent in that department either, he had plenty of paramours.

Marie-Madeleine, described as a charming, witty beauty with an air of childlike innocence, met a man named Jean Baptiste Godin de Sainte-Croix, who was introduced to her by her husband. Sainte-Croix was a cavalry officer fascinated with alchemy and pretty much without any money, who swiftly became her lover. Her husband did not care much for that, he continued to flaunt several mistresses and gamble his money away. The Marquise, in the meanwhile, flaunted her lover, who went by the title of Chevalier de Sainte-Croix, and financed his lavish life-style as well as her own. She seems to have done better than her husband money-wise, because he had to flee France and several creditors. Marie-Madeleine was thus allowed to control her own finances, which gave her even more freedoms.

Her relationship with the handsome Sainte-Croix became a bit of a scandal and so, in 1663, Marie-Madeleine’s father got hold of a lettre de cachet to put an end to the scandalous affair. A lettre de cachet was a sealed piece of paper signed by the King himself and countersigned by one of his Ministers. They were often used by the nobility to achieve something without the hassle of a lawsuit, like getting rid of a scandalous son. In the case of Sainte-Croix, it was a direct order of arrest.

He was arrested as he was in company of Marie-Madeleine and brought swiftly to the Bastille. Marie-Madeleine was, of course, outraged. Sainte-Croix remained in the Bastille for over a year and there he met a man named Exili. This man was an Italian once in service of Christina of Sweden and a certain Olimpia Maidalchini, someone close to the Pope. Not much is know about Exili or how he got to France, apart from rumours saying he was forced to flee Italy in order to escape some sort of conviction. While Sainte-Croix was in the Bastille with Exili, the latter told him one or two things about poison and how to get rid of people by using it in a way that would not cause suspicion. Sainte-Croix became an eager pupil of this man and as he was released, returned into the arms of the Marquise. They could only meet in secret however, the Marquise had promised her father to break with Sainte-Croix.

It’s not quite clear who came up with the devilish plan, but at some point both of them decided that Dreux d’Aubray must go. The Marquise and her lover needed money and, if her father would pass away, she, along with her sister and two brothers, would inherit a pretty penny. Marie-Madeleine organised the needed utensils and means to create a small laboratory, in which both experimented with different sorts of poison. According to reports, the Marquise then tried the mixtures on her maid and on the sick during several visits to the Hôtel-Dieu, a hospital for the poor and those in need.

Fifty people are said to be the victims of the Marquise and it is said she tried different kinds of poisons in various strengths on them, while noting the symptoms they created and how long the suffering lasted. The poison they used became later known as Eau Admirable and most likely contained arsenic, other poisons they used were heavy on mercury. Sainte-Croix taught Marie-Madeleine how to create the poisonous mix on her own and remained behind as the Marquise left for the countryside to take care of her father at his estate. Acting as his doting care-taker, Marie-Madeleine kept her father away from everyone and cooked his meals herself. Into those meals, she added the arsenic mixture over the period of eight months. Thirty little doses, as she said herself, until the hoped for signs appeared and her father died on September 10 in 1666. Dreux d’Aubray was thought to have died of natural causes and thus no autopsy was performed.

Sainte-Croix forced the Marquise to issue two promissory notes of 25,000 livres and 30,000 livres, in order to cover his expenses. That was a lot of money.

Marie-Madeleine did not inherit as much as she had hoped for, since she had to share with her siblings, thus those needed to go as well. She hired a certain Jean Stamelin, nicknamed La Chaussée, and placed him in the household of her younger brother. This younger brother shared an apartment with his older brother and La Chaussée was promised a nice sum for his assistance. The first attempt however failed. The poison was mixed into the wine of the brothers, who noticed an odd aroma in it and did not empty their glasses. The second attempt showed more success. As the brothers went to the Villeguoy during Easter time in 1670, La Chaussée laced their food with poison.

Seven people fell ill after a supper held in their house. All of those seven ate the same dish. Other guests, who did not, remained in fine health. The first brother died on July 17, the second three weeks later. This time an autopsy was performed, people found it a little suspicious that so many people got ill at the same time, and traces of poisoning with arsenic were discovered. The death of the brothers occurred at the same time as that of Henrietta of England, who was rumoured to be the victim of poisoning herself.

Although the physicians, who performed the autopsy, suspected poison to have been the cause of the brothers demise, the Marquis was not suspected. She was in Paris and had an alibi. La Chaussée was not suspected either, he was thought to be quite the loyal servant.

Her remaining family did get a little suspicious though. The Marquis thought it better to leave for the countryside in 1670 and her sister had everything she consumed tested for poison. In the meanwhile Sainte-Croix, completely ruined financially, wrote down what his lover had done to her family in his diary. He put that diary in a box along with several love letters the Marquise had written him, the two promissory notes and vials of the poison which they used. He did this to press her for more money in order to finance his expensive lifestyle. Unfortunately, for the Marquise, Sainte-Croix died shortly after on July 31, 1672. Most likely while experimenting and due to poisonous gas. Sainte-Croix continued to mix poisons as a science and without actually planning to use them. The poisons he studied were of such a fine a nature that inhaling the fumes, while cooking them, was enough to cause immediate death. He used a kind of glass mask to avoid inhaling them, but the mask dropped and broke.

He died childless and without having named an heir, thus an inquiry was made in order to settle his affairs during which the box was found with a note on it saying “To be opened in the event of death prior to that of the Marquise de Brinvilliers“. Marie-Madeleine swiftly fled the country.

More inquiries followed as the handwritten statement of Sainte-Croix was discovered and after the mixtures which were found in that box were given to animals, causing their dead. Several witnesses uttered their suspicions, which led to the arrest of the after all not so loyal La Chaussée. Like the Marquise, he had tried to hide himself previously, but was arrested on September 4.

Half a year later, on March 24 in 1673, la Chaussée was sentenced to death after torture, during which he confessed everything.

The Marquise left France for England and stayed there until her extradition was decided. Then ran off to the Netherlands. She stayed in Liège until, again, her extradition was agreed on. Rumours state that the Marquise had an affair with the Major of the city during her stay and tried to poison him as well. Marie-Madeleine was lured, under false pretense, into a cloister, where an officer disguised as priest arrested her. Her final trial took place in Paris and lasted from April 29 to July 16, 1676.

Despite being tortured, the Marquise did not name any accomplices. Apart from being accused to have poisoned her father and brother, the Marquise was also accused of having poisoned fifty people during her visits to the Hôtel-Dieu, to have tried to poison a maid, to have poisoned one of her children, to have intended to poison her husband in order to marry Sainte-Croix, which did not want to marry her and gave the Marquis an antidote, and to have tried to poison her majordomo.

She later confessed to have committed incest, to have murdered her father and her brothers, to have tried to murder her sister (which in the meanwhile had died of natural causes), she admitted to have tried to poison her husband, but then decided against it and gave him antidotes, to have committed adultery and masturbation, to have slept with her cousin, to have taken drugs in order to abort a child and to have poisoned her maid. As motive she stated a need for independence and money.

On July 17 in 1676, the Marquise was brought to the gates Notre-Dame for Atonement, then to the Place de Grève, the place of public executions. Marie de Rabutin-Chantal, Marquise de Sévigné, described the scene in one of her letters: “At six o’clock, she was taken in a cart, wearing only a shirt and with a rope around the neck, lying on straw, to Notre Dame to make amends. Then they drove her further on the same cart. I looked at her, she was lying on the straw, dressed only in a shirt and a low hood. A priest next to her and the executioner on the other side. Truly, I shuddered. Those who have attended the execution, said that she has courageously climbed the scaffold. I was on the Bridge with the good Escars. I never saw such a crowd before and never was Paris so moved and excited.”

Marie-Madeleine Marguerite d’Aubray climbed the scaffold barefoot and with much dignity. The executioner was in no hurry and toyed with her hair for a long time. The Marquise was beheaded and her head thrown along with her body into a pyre. Her remains then shattered and thrown into the Seine.

The Marquise de Sévigné remarked: “Well, it’s all over and done with. Brinvilliers is in the air. Her poor little body was thrown after the execution into a very big fire, and the ashes to the winds, so that we shall breathe her, and through the communication of the subtle spirits, we shall develop some poisoning urge which will astonish us all…“

3 Comments

Tess

Fifty victims during the preparation! She truly wanted to make sure that everything will succeed. Or she really liked her new hobby. Probably both…

AuroraVonG

And a maid or two, just to make sure…..

Adele

This all reminds me of those words…..”Oh what a tangled web we weave, when first we practise to deceive….”

As I continue reading “Charlatan”, I realize how diabolical that whole time was, and how you had to always watch your back, and trust no one.

Thanks, another very interesting article.