Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, Duchesse de Montpensier

She was a grand-daughter of Henri IV, niece to Louis XIII, first cousin to Louis XIV, a woman determined to control her own life and fortune. An amazon in a world of delicate women, commonly known as La Grande Mademoiselle.

Anne-Marie was born at the Palais du Louvre in Paris on 29 May in 1627 as first child of Gaston de France, brother of Louis XIII, and the twenty-one year old Marie de Bourbon. Marie was the sole heiress of the vast Montpensier fortune and Duchesse de Montpensier as well as Princesse Souveraine de Dombes in her own right. Aged two, she was engaged to the second born son of Henri IV, commonly known as Nicolas-Henri de France because he died before he was baptised and officially named. After the demise of the boy, who only lived four years, Marie was engaged to his brother Gaston, the third born son. Gaston was not too happy about it, but Cardinal de Richelieu was determined the marriage should take place. After all, Marie was the richest girl of France, a descendant of John II of France of the House of Valois and of Louis IX aka Saint Louis…

The wedding was celebrated in Nantes on August 6 in 1626 in the presence of Louis XIII, Anne d’Autriche and Marie de Médicis. A sadder wedding was never seen, wrote the biographer Vita Sackville-West, quoting a member of the court.

Marie died due to puerperal infections only six days after the birth of Anne-Marie, making her the richest baby in France since the little girl inherited all of her mother’s fortune.

As the eldest daughter of Monsieur, the title of the King’s brother, Anne-Marie was officially known as Mademoiselle from the time of her birth, and, because she was the granddaughter of a King of France, Henry IV, her uncle Louis XIII created a new title for her, that of petite-fille de France.

Anne-Marie was moved from the Louvre to the Palais des Tuileries after the death of her mother and given into care of Jeanne de Harley, known as Madame de Saint-Georges, who was made head of the Household of the little girl. Papa Gaston, unfortunately, did not care much for his daughter. He seems to have hoped for a boy. At that point, Gaston was the heir to his brother, since Louis XIII and his wife Anne d’Autriche had not yet produced an heir… and Gaston had high hopes that he, or his son, might be King of France one day. Thus he involved himself in various intrigues and spent a lot of time abroad, in exile.

In the meanwhile, his daughter grew up under the care of Madame de Saint-Georges, who taught her how to read and write, and in company of Mademoiselle de Longueville and the sisters of the future Maréchal de Gramont.

Nevertheless, Mademoiselle adored her papa no matter what. As she was four years old, he married again… but without permission of Louis XIII. While his first marriage was an arranged one, this second one was for love. His bride was Marguerite de Lorraine and since he married her without permission of the King, both could not appear at court and the marriage had to be kept secret. On top of it, Lorraine and France were not on friendly terms. They managed to keep the whole thing secret for half a year, until the Duc de Montmorency, who was in the know, spilled the beans on his way to the scaffold… maybe as a bit of a revenge on Gaston, who had abandoned his former co-conspirator. Louis XIII has his brother’s marriage declared void in 1634 and Gaston was exiled. Little Mademoiselle was outraged and as she got wind of the Cardinal being involved in her father being exiled, she sang some cheeky anti-Cardinal songs in his presence. Getting her a fine scolding from the Cardinal, who happened to be her Godfather.

Said Cardinal, as well as Louis XIII, intended to marry Mademoiselle one day to a great Prince, thus it was made sure Anne-Marie received a very good education. While she only knew little affection from her papa, the King and Queen held her quite dear. Anne-Marie was seven years old as she saw her papa again. She met him at Limours and flung herself into his arms. Gaston afterwards resided at Blois and was often visited by his daughter. He too had plans for his daughter, she ought to marry Louis de Bourbon, Comte de Soissons, a prince du sang and old friend.

But Anne-Marie was still too young to marry anyone at that point… and by the time she was, she refused suitor after suitor, determined to choose her own hubby. A scandal of great proportions in a world of male family members deciding such things.

Mademoiselle even had someone in mind already, a special someone. As the future Louis XIV was born in 1638, and her papa climbed one step down on the becoming-King-of-France-ladder, Anne-Marie declared she would marry her cousin one day. Even calling him her little husband. Louis XIII was quite amused by all of it, Richelieu not so much. He reprimanded her for her bold remarks… but not with much effect. Anne-Marie was rather stubborn once she decided for something, even as a child.

As Madame de Saint-Georges died in 1643, Anne-Marie was devastated. Her father decided for Madame de Fiesque as new governess, but Mademoiselle was not fond of that decision at all. She was rather unkeen on having a new governess and even locked Madame de Fiesque, as well as her grandson, into their rooms. The very same year, a big change occurred in France.

Louis XIII died and the new King, Louis XIV, was still a small child. He needed a Regent, Gaston had hoped he might have a role in it, but Anne d’Autriche took over the Regency. Gaston was no longer brother to the King, but now uncle to the King… and the King’s little brother Philippe. Luckily for Gaston, his brother forgave him for the matter with the secret marriage before his death and gave his permission to Gaston to marry Marguerite properly, thus both were allowed to appear at court and Marguerite could officially style herself Duchesse d’Orléans.

In 1646, Mademoiselle met Charles Stuart, future Charles II of England. He was sixteen then and his French mother Henriette-Marie, sister of Louis XIII, introduced the idea that Anne-Marie could marry him. Saying that her son had taken a fancy to her, who was so different from all the other girls… but nothing more was said about it at the time. And while Mademoiselle was somewhat interested in first, she ceased to be so quickly. Then Maria-Anna of Spain died and Anne-Marie showed an interest in marrying her widower, Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III… but Anne d’Autriche didn’t want to hear anything about that. She suggested her own brother instead, Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand… Mademoiselle declined politely. She still had in mind to marry Louis XIV, or his brother, although both Anne and Cardinal de Mazarin said no to that. And then, the Fronde happened.

Mademoiselle sided with her cousin, le Grande Condé, entertaining the thought of marrying him. She previously had made friends with Condé’s wife, Claire Clémence de Maillé-Brézé, a niece of Cardinal de Richelieu. As the latter fell ill with erysipelas, Mademoiselle considered to marry Condé. Madame Condé recovered, but Anne-Marie still sided with Condè, who was in rebellion against the crown. In 1652, during the second part of the Fronde, called the Fronde des nobles/princes, Mademoiselle travelled to Orléans, the capital of her father’s Duchy. Gaston could not really decided on which side he was and as Orléans called for advice on how to handle to situation, considering what had happened to other towns previously, Anne-Marie took it upon herself to act. She travelled there to represent her father, but was not welcomed with open arms. Still on the way, she was informed that the city would not let her enter, because she and the King were on different sides.

Anne-Marie continued her voyage anyway, finding the gates of the city locked to her. She shouted that they should be opened at once, but was ignored. Stubborn as she was, she took the offer of a boatman to take her to the Porte de La Faux, a gate on the river. She entered the small boat, climbing like a cat and jumping over the hedge, and slipped through a little gap in the gate. All of Orléans was besides itself in admiration of such a daring woman. She was greeted triumphantly and carried through the streets of Orléans on a chair for all to see. She later said she that she had never been “in so entrancing a situation“.

After five weeks in Orléans, Mademoiselle returned to Paris and did something that would forever change her life. She had the cannons of the Bastille fired. At the royal troops. In the general direction of the King. Cardinal Mazarin remarked with that cannon, Mademoiselle has shot her husband.

Her reputation ruined and having earned the distrust of the King, he exiled her thus.

Mademoiselle settled at the château de Saint-Fargeau, a Renaissance château in Burgundy. Said château was not in a too good state and it was the first time Anne-Marie ever visited it… but alas, she had to turn it into a home, since a swift return to court seemed rather unlikely. After all, she had left Paris fearing for her very life. Luckily, Mademoiselle was still the richest woman in France. François Le Vau, brother of the renowned architect Louis Le Vau, was hired to make improvements here and there. He redid the exteriors of Saint-Fargeau at a cost of 200,000 livres, making the crumbling castle worthy to host someone of Mademoiselle’s rank. Although in exile, Anne-Marie still travelled to visit her papa at Blois often. He lived there in exile as well, but in company of his wife… and children. Gaston and Marguerite were the proud parents of three daughters and one son by then. The son, the only Gaston ever had, died in August 1652, not yet aged too. The same year, another daughter was born, which only lived four years.

Anne-Marie was quite fond of her stepmother, a gentle and pious woman. She also adored her siblings much, especially Françoise-Madeleine.

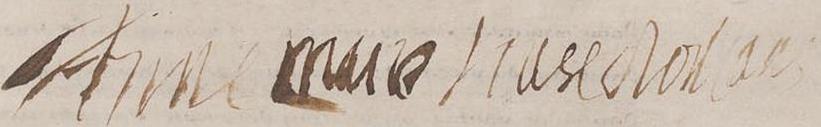

Being exiled could have been worse for Mademoiselle. While at Saint-Fargeau, with plenty of free time at her hands, she began to write. It was a small biography, written under the name Madame de Fouquerolles, full of bad spelling and grammar. She also had a closer look at her finances and noticed, to her shock, that her papa, who had taken care of them until her majority in 1652, was not entirely honest with her. And that her father was also involved in her grandma Henriette Catherine de Joyeuse, the Dowager Duchesse de Guise, tricking her into signing away money to her under false pretences. Mademoiselle was shocked by the discovery. Although she adored her papa, never minding his own lack of interest in her, she could not forgive him such a betrayal of her trust for quite a while.

It was not until Gaston was pardoned by Louis XIV in 1656, that Anne-Marie did so. Saying she would try to forget the bad blood caused by his financial misdemeanours. Papa’s return to the good graces of the King, also paved the way for Mademoiselle’s return. She left her country residence for Sedan, where the court resided in 1657, and was warmly greeted by her family, having not seen some of them for over five years. Various compliments were exchanged and Anne d’Autriche even complimented her on her looks.

That probably flattered her quite a bit. Anne-Marie was quite aware that she did not really meet the beauty standards of the time. She was a tall woman, neither fat nor thin, as she said herself. Healthy looking, with a bosom that is fairly well-formed, adding my hands and arms not beautiful, but the skin is good.

Mademoiselle was thirty years old then, headstrong, a heroine in the eyes of the former Fronde rebels… and still not married… a bit of an old maiden, some said.

Despite all that happened during the Fronde, especially the cannon episode, Anne-Marie still entertained the thought of marrying Louis XIV, then aged nineteen. The thought of marrying Philippe, then seventeen years old and known as le Petit Monsieur to distinguish him from her papa, who went by Monsieur, had become less of an option. She had considered it, after all both of them were close friends and it would be a fabulous match… Philippe even courted her for a while and entertained the marriage idea himself… but the fact that he seemed to be still, despite his age, a bit clingy to his mother, like he was still a child, as she said, made her dismiss the idea in the end.

Back at court, Mademoiselle enjoyed life, often in company of Philippe, only interrupted by a brief illness in September 1657. But then in 1660, Gaston died at Blois. Mademoiselle, as his oldest child, inherited a lot of his fortune. The title Duc d’Orléans went to Philippe, with another part of the fortune coming with it. As custom, the court went into mourning for Gaston, son of le Bon Henri IV, while in the background preparations for a marriage went under way. That of Louis XIV.

The bride was not Anne-Marie, obviously, but only then she stopped to entertain the thought of being it. Louis married the Spanish Infanta in 1661 and Mademoiselle, still in mourning, was officially only allowed to attend the formal wedding… but sneaked her way into the proxy ceremony as well. Incognito, yet fooling no-one as to who she was.

The new Duc d’Orléans married the following year, not Mademoiselle either. She remained single and enjoyed her freedom. Hosting a salon, going to balls and to the theatre with her half-sister Marguerite-Louise. The King approached Anne-Marie in 1663 with the idea of a possible match for her. He had in mind to marry her to Afonso VI of Portugal… but Mademoiselle did not want to become Queen. She said she wished to remain in France, with her fortune, being not desirous to have a hubby rumoured to be alcoholic, impotent and paralytic. Thus Afonso VI married Mademoiselle d’Aumale, a granddaughter of Henri IV and his mistress Gabrielle d’Estrées.

Louis XIV, just as head strong as Mademoiselle, did not quite like to be rebuffed by Anne-Marie like that and exiled her once more. He ordered her to return to Saint-Fargeau for disobeying. Again, Mademoiselle reached for quill and parchment, using the spare time to begin writing her now famous memoirs.

This exile did not last as long as the first one, however. Mademoiselle managed to talk Louis into letting her return to court, for the sake of her health. So, Mademoiselle was back where she belonged after a year… and confronted with another proposal regarding marriage by her cousin and King. This time the suggested groom was Charles-Emmanuel II, Duc de Savoie. Also a grandchild of Henri IV, his mother being the sister of Gaston and Louis XIII. Charles was a widower, for his wife, Françoise-Madeleine, half-sister of Anne-Marie, had passed away recently, aged only fifteen.

For once, Anne-Marie was actually quite pleased with the suggestion. This Charles seemed decent enough and Savoy was not too far away, in fact it was almost France. But, alas, this Charles saw the matter different and made excuse after excuse… Mademoiselle remained single. It was the last proposal of marriage for her… at least officially.

The marriage chapter was not yet over for Mademoiselle and she caused quite the scandal with it. At some point after her return, Anne-Marie took an interest in the Duc de Lauzun.

Antoine Nompar de Caumont, an impoverished nobleman, who had a strange like-dislike relationship going on with Louis XIV, a great jester, full of himself, with an ego only challenged by that of the King, the smallest man God ever made, as Mademoiselle said, yet with a sex appeal hard to resit for her.

Mademoiselle fell hopelessly in love with Lauzun. Next to the Fronde, this was probably the most turbulent time in Anne-Marie’s life. As Monsieur’s wife, Minette, died suddenly, Louis XIV suggested jestingly Mademoiselle should take the vacant place. She went all pale at the thought of it, for she had in mind to marry that cheeky Lauzun by then. He was rather bold and not always very kind to her… but Anne-Marie saw him through rose-tinted glasses and her mind was made up on the matter.

Thus she went to the Sun King to inquire for permission to marry Lauzun, who she already called Monsieur le duc de Montpensier in company of her friends. Surprisingly, Louis agreed to the match… for whatever reason. Mademoiselle was beside herself with joy, but only for a couple of days. Pressured by court, wife and brother, who said they will not sign the contract of marriage, Louis changed his mind.

Anne-Marie dived deep into despair and secluded herself in her apartments. Not reappearing until the beginning of 1671… just to be swallowed by despair again as she learned Lauzun had been thrown into the Bastille… and nobody could tell her why. He was afterwards transferred to Pignerol, the very fortress where Nicolas Fouquet was held prisoner. Mademoiselle surely thought she would never see her beau again. And said beau most likely thought he would never get out of that place again… he tried to escape several times, but was caught again and again.

Battling her despair, Mademoiselle gathered all her strength to fight for the release of her beloved. Anne-Marie was, next to the oldest daughter of the King, the most senior woman at court, but, unfortunately, she had not many friends. And apart from Monsieur, not really any friend in a position to help. Madame de Sévigné thought little of her too, describing her as very stingy and cold. Most of the court was rather jealous of her, for Anne-Marie was not just the richest woman of France by then, but the richest woman of Europe. Thus Anne-Marie turned to the person closest to the King, Madame de Montespan. A bit of a mistake.

La Montespan did help in her own way. She talked with the King about Lauzun’s release and the latter saw it as a chance to make Mademoiselle a little less rich… he talked her into selling two of her most profitable lands, which he then gave to two of the sons he had with la Montespan.

Anne-Marie agreed, thinking her sacrifice would restore her beau to former glory, but unbeknown to her, in first, it only bought his release and allowed him to live on her estates as an exile. Lauzun became a free man again, after ten years as prisoner, but was not allowed to return to court. Both of them argued and argued, which in the end led to their separation. (This whole story is so entertaining and there is much more to it, that it will get an own article soon.)

Mademoiselle retired to her Parisian residence, the Palais du Luxembourg. After the episode with Lauzun, she lived a bit of a quieter life. Anne-Marie fell ill 15 March in 1693, due what seems to have been stoppage of the bladder. Hearing of it, Lauzun knocked on her door, asking to see her, but she refused. Out of pride. She died at the Palais du Luxembourg on 5 April in 1693, a Sunday.

Being a petite-fille de France, Mademoiselle was buried among the family at Saint-Denis. Lying in state, the urn containing her entrails exploded mid-ceremony, which caused chaos as people fled to avoid the smell.