Carrosses à cinq sol, the first public transport system of the world

Many things of our modern world have their origin in 17th century France and were invented during the reign of the Sun King. Champagne is one, public street lighting a other, high heels as well, public transportation too. The Carrosses à cinq sol -carriages for five sol- have their origin in the year 1661 and were the very first public transport system of the world.

Paris counted 530000 inhabitants and was the fifth largest city of the world. Nine bridges, over five-hundred streets, around twenty-two-thousand houses and one-hundred more or less public places like gardens and squares. Something like a private taxi service was already around for a while. People could hire carriages –fiacres- for a specific amount of hours or a whole day, but that could get a little expensive.

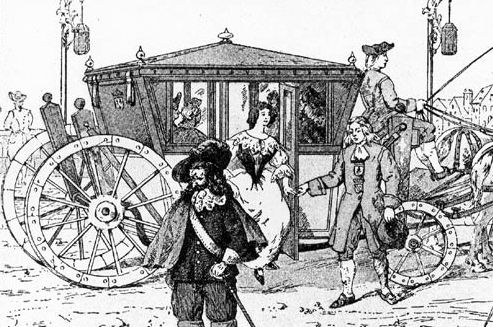

Artus Gouffier de Roannez, Duc de Roannez, teamed up with Pierre de Perrien, Marquis de Crenan and Grand Échanson de France, and Louis François du Bouchet de Sourches, Marquis de Sourches, to create a cheaper and more accessible version of the fiacres. Their idea was simple. A set amount of carriages was to drive through Paris on set routes and would stop at set places along the route. A horse-powered bus service. Each passenger was to pay five sols, hence the name, no matter if he was the only passenger or not.

The mastermind behind it was a certain Blaise Pascal, a known mathematician, physicist and inventor. He also suggested that people with lesser means, which were unable to pay five sols, should only pay two. An idea that was implemented as the concept was brought to Louis XIV in 1661. The King allowed them to go ahead on January 19 the following year and Paris saw its, and the world’s, first public transportation system in action for the first time on March 18 in 1662.

The first line had seven carriages and connected the Palais du Luxembourg with the Porte Saint-Antoine. On April 11, a second line was added and connected the Rue Saint-Antoine, via the Rue Saint-Denis, to the Rue Saint-Honoré. A third line, starting on May 22, connected the Palais du Luxembourg with the Rue Montmartre. The fourth line was added on June 24 and received the name Route du Tour-de-Paris, for it circled Paris in its whole. Since this line was rather long, something new was invented for it. The route was put into smaller sections, six of them, and depending on how many sections a passenger wanted to cross, the price increased. Just like today. The last line was added on the 5th of July and connected the Palais du Luxembourg, via Notre-Dame, to the Rue de Poitou.

Blaise Pascal initially planned for more routes, which might have been added at some point, but the documentation for them is missing.

The lines operated from seven o’clock in the morning to eight o’clock in the evening, in both Summer and Winter. Each carriage, bearing the coat of arms of the city of Paris, had eight seats and was drawn by two horses. Colour coding was used to distinguish between the different lines. The carriage-driver, and the valet assisting him, wore blue coats with differently coloured accessories depending on the line they served.

Together all lines were about twenty-three kilometres long, fifty horses were in use, and the approximate travelling speed about nine kilometres and hour.

The Parisians loved the whole thing….. until the Parlement de Paris got involved. They ordered that soldiers, lackeys, pages, and people dressed in any kind of Livree, were not allowed to use the service, in order to keep the seats free for the Bourgeoisie and those that had more means. The people that were excluded from the service did not like it at all and started to protest, sometimes even violently.

As the prize was raised to six sols and the carriages not properly maintained, the service became quite unpopular. The Parisian police forces got a little sick of all the fuss and set up a degree stating that anyone who disturbed the service anyhow was to be punished by whipping.

The poor maintenance, increased pricing and growing unpopularity were the reason why the whole thing was cancelled in the end. It is not exactly known when, but it seems to have been some-when between 1677 and 1680.

Around one-hundred-fifty years later, in 1829, the service was re-introduced to Paris and more successful.