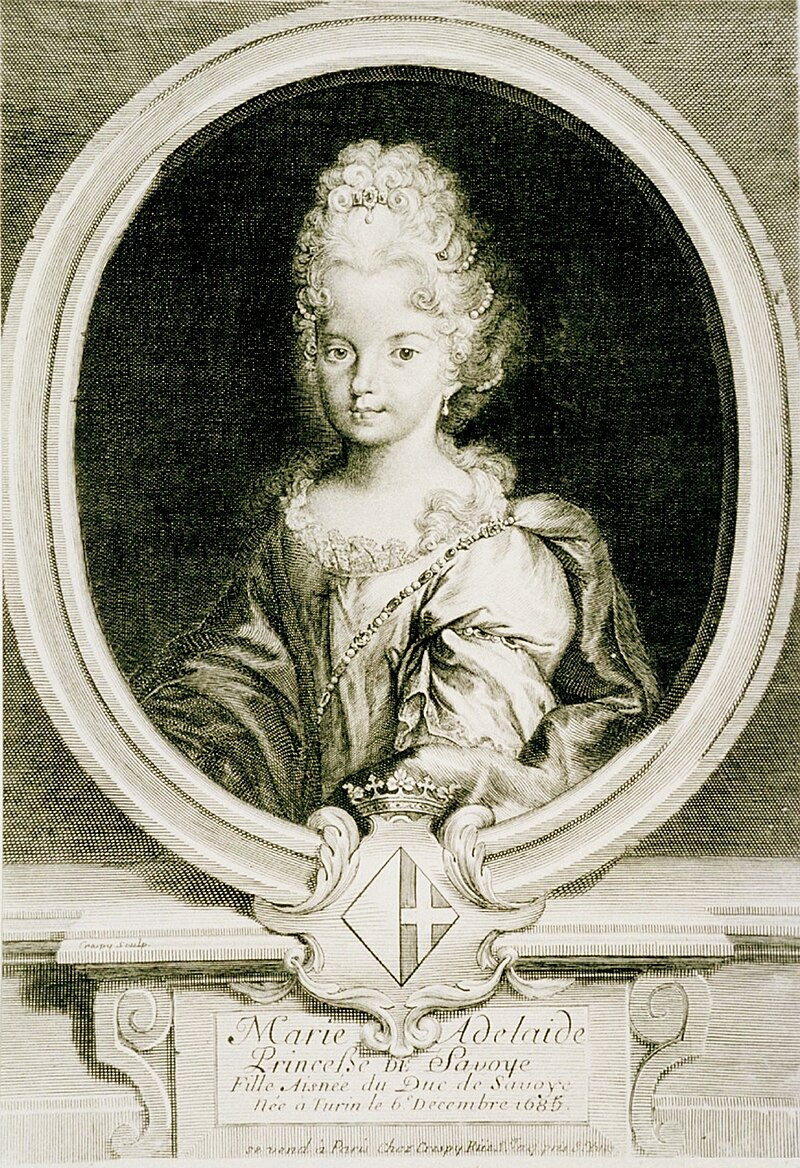

Marie-Adélaïde de Savoie, Duchesse de Bourgogne et Dauphine de France

Marie-Adélaïde de Savoie was certainly on of the most sparkling gems of Louis XIV’s Versailles and the mother of Louis XV. She was born in Turin on 6 December in 1685 to Victor-Amédée II, Duc de Savoie, and Anne-Marie d’Orléans.

Anne-Marie d’Orléans was a daughter of Monsieur, brother to Louis XIV, and his first wife Henriette d’Angleterre, sister of Charles II. She married Victor-Amédée II, a grandchild of Louis XIII’s sister Christine de France, in April 1684. Pretty much nine months later, Anne-Marie nearly died during the birth of their first child, a daughter. She was only sixteen and the birth so difficult, that she received the Last Rites because it was feared she could die any moment.

Anne-Marie d’Orléans was a daughter of Monsieur, brother to Louis XIV, and his first wife Henriette d’Angleterre, sister of Charles II. She married Victor-Amédée II, a grandchild of Louis XIII’s sister Christine de France, in April 1684. Pretty much nine months later, Anne-Marie nearly died during the birth of their first child, a daughter. She was only sixteen and the birth so difficult, that she received the Last Rites because it was feared she could die any moment.

The Duchesse recovered, slowly but surely, and contrary to what was considered proper for noble women, she actually raised the child herself. The little girl was baptised Marie-Adélaïde, with her grandmother Marie-Jeanne-Baptiste de Savoie and Emmanuel-Philibert de Savoie-Carignan acting as godparents. Little Marie-Adélaïde was rather fond of her grandmother and visited her frequently.

She was the sort of girl to take hearts by storm. Sweet natured and lively, always smiling and embracing. And as the years passed, the little girl became more and more beautiful. A perfect Princesse.

Princesses, perfect or not so perfect, all share a fate. They are as much a political asset as they are beloved daughters. If wedded to the right person, they can secure peace for their native land. Marie-Adélaïde was only around ten years old as the negations for a possible match started. Her papa had in mind to marry her to Austria, that is to the Archduke Joseph, the eldest son of Emperor Leopold I from his third wife. Emperor Leopold declined, due to the young age of Marie-Adélaïde.

Louis XIV did not. As part of the Treaty of Turin, Victor-Amédée’s French-born mistress Jeanne-Baptiste d’Albert de Luynes and the Comte de Tessé arranged a match for Marie-Adélaïde. The Treaty was meant to smooth the relationship of both countries and the marriage was supposed to seal the deal. Marie-Adélaïde, tender eleven years old, should be send to France in order to be educated for her future role at court… and that was quite the major role, for Marie-Adélaïde’s groom was the oldest son of the Dauphin, which meant she would be Queen of France one day. Monsieur, her grandpa, was beside himself with joy at the thought.

Her mother, who was in constant contact with her native France, prepared the little girl very well for what she had to expect at the Sun King’s court. She taught her the who is who, the who to avoid, to whom she should be especially kind to, what the King enjoyed and what he did not enjoy, what her grandpa, Monsieur, liked and how she could please both. Marie-Adélaïde departed from Savoy and crossed the French border on 15 October in 1696 without entourage. The Comte de Brionne, the oldest son of Louis de Lorraine and therefore a nephew of the Chevalier de Lorraine, picked her up at the border and escorted her to Montargis, around 110 kilometres south of Paris.

She met Louis XIV there for the first time on 4 November and the great Sun King was at once utterly taken with her. He wrote the following about this meeting to Madame de Maintenon: “She has the most graceful and perfect figure that I have ever seen; her dress and hair are like a picture; her eyes bright and very handsome, with admirable dark eyelashes; her complexion smooth, and as pink and white as heart could wish; and she has the most beautiful brown hair that you can imagine, and in great quantity; her mouth is red, her lips large, her teeth white, long, and very irregular; her hands are well shaped, but of the colour of her age. I am extremely pleased with her, and I hope you will be so too when you see her.”

Madame de Maintenon was indeed very pleased as well. Marie-Adélaïde greeted her warmly and addressed her with a slightly improper but very endearing ma tante. She wrote in a letter to Anne-Marie d’Orléans: “Your Royal Highness, will hardly believe how pleased the king is. Yesterday he did me the honour to say that he will have to be careful in what he says or people will think that he is exaggerating… She has a natural courtesy which makes it impossible for her to say anything unkind. Yesterday I tried to resist her caresses, saying that I was too old, to which she replied, “Ah, point si vieille!” She came up to me, when the king had left the room, and kissed me. Then she made me sit down, having noticed at once that I cannot stand, and, almost seating herself on my lap, she said in a coaxing voice, “Mamma told me to give you a thousand messages from her, and to ask for your friendship for myself. Please tell me what I must do to please you.” Those are the words, Madame, but the gaiety, the gentleness and grace, with which they were accompanied, cannot be put on to paper.”

Monsieur was just as taken with his granddaughter. He went to Montargis along with the King and the Dauphin, and was so full of joy upon seeing his sweet grandchild for the first time, that he forgot all protocol and went to greet, kiss and embrace her, before it was his turn. It was probably the first and only time he ignored etiquette. Marie-Adélaïde loved to tease him about his big belly and visited Saint-Cloud often. As Monsieur died in 1701, she was beside herself with grief for a long time.

Madame, her step-grandma, was not so much of a fan. She thought Marie-Adélaïde was only acting and her affections trained and not honest. She later on suspected her of making fun of her and talking badly to the King of her. Liselotte could not at all understand why everyone loved Marie-Adélaïde so much. For her, she was pretty much a spoiled child without manners and respect. Saint-Simon wrote about her: “She was kind to everybody, even to the least influential and the most unimportant, without any appearance of conscious effort. One was tempted to think her wholly devoted to the people with whom she happened to be for the moment.”

Versailles got a little less dull with the arrival of Marie-Adélaïde. Fêtes and comedies returned as did afternoon amusements. It was as if the court woke from a long slumber. Louis XIV, extremely pleased with her, sought to please her in return and arranged for all sorts of entertaining distractions. He too was as if awoken from a long slumber. He smiled more, laughed more, dressed better and even wore some jewels from time to time. In contrary to his own children and grandchildren, who had been brought up to feel more awe than affection for him, Marie-Adélaïde was a fresh breeze for Louis. She was not afraid of him, not in the least, and thus there was no restrain on her side.

Versailles got a little less dull with the arrival of Marie-Adélaïde. Fêtes and comedies returned as did afternoon amusements. It was as if the court woke from a long slumber. Louis XIV, extremely pleased with her, sought to please her in return and arranged for all sorts of entertaining distractions. He too was as if awoken from a long slumber. He smiled more, laughed more, dressed better and even wore some jewels from time to time. In contrary to his own children and grandchildren, who had been brought up to feel more awe than affection for him, Marie-Adélaïde was a fresh breeze for Louis. She was not afraid of him, not in the least, and thus there was no restrain on her side.

She jested with and about him, she teased him and at times she even scolded him. She ran to him to embrace him and kiss his cheeks, jumped on his lap, rummaged in his important papers and yawned when he was too busy to pay her the attention she desired. He loved it. It was a new experience for him and rejuvenated his spirits. Saint-Simon relates the following exchange as Louis and Madame de Maintenon talked about Queen Anne: “‘ Ma tante,’ one must admit that in England the queens govern better than the kings: and do you know why, ma tante? The reason is that, where there are kings, women govern; and where there are queens, men.” Both, the King and his secret wife, laughed heartily and agreed that she was in the right.

Marie-Adélaïde was already Louis’ favourite as it was finally time for the wedding to go ahead. Until then, Marie-Adélaïde had visited Saint-Cyr three times a week to be prepared for her duties. On 6 December in 1697, her twelfth birthday, the marriage contract was signed and Marie-Adélaïde was wed to Louis de France, Duc de Bourgogne, the following day. The Sun King did not wish too much ado in regards of celebrations, only two balls, an opera and a firework. But everyone had to appear in new court robes. The bride was dressed in a gown of silver fabric, covered all over with rubies, and featuring a trail of 8 metres length.

After the nuptials and some celebrating, le Petit Dauphin, as the Duc de Bourgogne was called, was permitted to give his bride a peck on the lips and to accompany her to the bedchamber, where he was, ceremonially, allowed to place himself in the bridal bed for a moment, before being shooed out. Later that evening, he attempted to sneak back in and was caught in the act by a chamber-woman, who, using profanities, showed him back out at once and reported the incident to the King. A fine scolding followed the next day and Louis was reminded, that he may kiss his wife, now and then, when the situation was fitting, but that was all. No touching or other things until she turned fourteen.

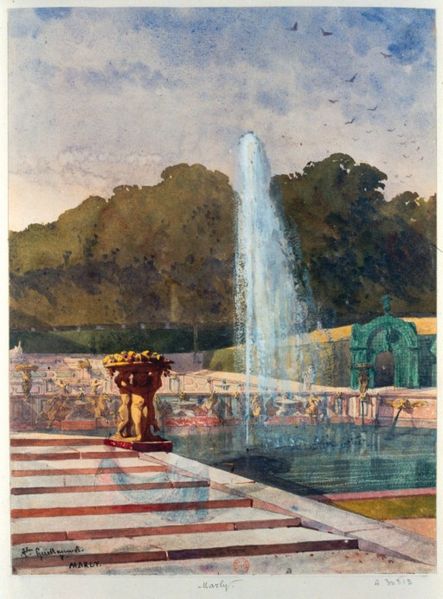

Until then, there were plenty other things to do and the new Duchesse engaged happily in them. She loved to play tricks on people. The Duc and Duchesse de Bourgogne played a trick on the Princesse d’Harcourt at Marly one time. They arranged a series of bombs along the avenue that led from Marly to the Perspective, where the Princesse d’Harcourt lodged. As the Princesse was half way up the allee in her sedan chair, the bombs began to explode. Her porters were in the know, dropped the chair and fled at once, while the Princess was left struggling and shrieking inside. The rest of the court was also in the know and watched the screaming Princesse in her struggle from a distance, highly amused. A other time, while visiting Marly in winter, the Duchesse de Bourgogne and her companions broke into the bedroom of the Princesse d’Harcourt and snowballed her in her bed. Shortly after, the Duc de Bourgogne placed petards under the chair of the Princesse d’Harcourt on which she used to sit at the cart-table. Fortuanetly for her, a friend of the Duc said the explosion might tear the Princesse into pieces and kept the Duc from firing them.

The Duchesse was also extremely fond of card games, especially of lansquenet. This worried Madame de Maintenon quite a bit. Lansquenet was a game dating back to the Thirty Years’ War and named after the French spelling of the German word Landsknecht. It was very popular at court and one could win and lose high amounts. Madame de Maintenon was not at all fond of gambling and Louis XIV was not too fond of it anymore either. Thus he was not impressed as he learned of the Duchesse playing Lansquenet with some random gentlemen after a picnic.

Something else that worried Madame de Maintenon was that the Duc seemed way more in love with the Duchesse, than the Duchesse with him. She liked him, was affectionate with him, but it did not quite seem that she loved him as much as he loved her. Madame de Maintenon was constantly afraid that, due to the youthful spirit of the Duchesse, she might say or do something to compromise her husband. Marie-Adélaïde could be quite indiscreet… she jested in public about how pious her husband was… but she probably thought not much of it and meant no harm, after all she was of the generation that made fun of everything, as she said herself.

The Duc and Duchesse had three sons born between 1704 and 1710. All three were named Louis and only one reached adulthood, the future Louis XV.

More dangerous than gambling, playing tricks and teasing people, is probably flirting. Especially for a future Queen of France, who ought to be the embodiment of virtue and grace. Who ought to serve her husband, no matter how boring he might be. Marie-Adélaïde was beautiful and had a fair share of ardent admirers… much to the displeasure of Madame de Maintenon, who always kept an eye on her…. but girls just wanna have fun. The court did not just whisper about it, they watched all of it. But with no evil spirit. Hardly anyone seemed to have judged her for it.

Among her admirers were a Monsieur Nangis, very handsome, not too smart, but a great ladies’ man, and Monsieur Maulevrier, a nephew of Colbert, very ugly, but very skilled and ambitious. Unknown to the other, the Duchesse exchanged looks and words with both as well as secret missives. She did not care much for rank and such things. One time the Dauphin, her father-in-law, wanted to host a public ball and wished her to be present. Louis XIV disagreed strongly with the idea, for it would mean his favourite would dance with all sorts of men. He got into a heated argument with the Dauphin about it. Marie-Adélaïde simply said she did not care if the man she dances with, is a King, a prince of the blood, a nobleman, a soldier or a nobody. It was all the same to her, as long as she could dance with someone. In case of Maulevrier and Nangis, things got even more heated. Maulevrier, not wanting to leave court to participate in a campaign, feigned and illness and pretended to have lost his voice. He locked himself in his room and only consumed milk, acting the weak sick man. The Duchesse visited him often and stayed for quite a while. The court watched all amused how much she cared for the health of the gentleman.

While Maulevrier’s illness was feigned and not real at all, something else was. He had mental health issues and bordered on insanity. At some point, he, being all sure of the Duchesse’s affections, found out he had a rival. Taking the first opportunity, he confronted the Duchesse about Nangis. She was just returning from mass and he offered to escort her back to her rooms, something Monsieur Dangeau usually did, but he was not present that day. Maulevrier whispered to her what he had found out on the way and talked bad of his rival. Then threatened to spill the beans to the King, la Maintenon, the Dauphin and her husband, while he held her hand so firm in his, that it was nearly crushed. Marie-Adélaïde panicked as she reached her rooms and told everything to Madame de Nogaret, who advised her to be very careful with Maulevrier or he might completely lose it. Shortly later, Maulevrier tried to pick a quarrel with Nangis to provoke him to make a scene in public, which would have caused great ado once the reason for it emerged. Nangis however was smart enough to not let himself be provoked. He knew what was going on and fearing for his very future at court, decided to avoid Maulevrier as best as he could. This went on for a long six weeks during which Marie-Adélaïde constantly feared impending doom.

The friend’s of the Duchesse came for the rescue. They informed the father-in-law of Maulevrier, who happened to be the Comte de Tessé, and he decided that since the illness Maulevrier suffered of had still not been cured by the doctors, Maulevrier should accompany him to Spain for a change of air. Maulevrier stayed in Spain for a year and by the time he returned, his state of mind had changed from bordering on insanity to completely insane. He started to bombard Marie-Adélaïde with threatening letters and the whole thing only came to an end, because he, in a fit of insanity, jumped out of a window and did not survive. Louis XIV, the Dauphin and the Duc apparently never found out about it.

As the Duc returned from a failed military campaign and all blame was put on him by an intrigue aiming to discredit him, Marie-Adélaïde, in love with him or not, was steadfast at his side. She tried what she could to make the situation better, but had not too much success. The people around the Duc de Vendôme spread all sorts of things about her husband and the King believed them. The Duc de Bourgogne was not greeted warmly as he returned to Versailles and it took quite a while until the truth became known.

The Duc was not entirely without fault for the failed campaign, but Vendôme was not innocent either. Only after the high-ranking officers returned as well and told the King of what happened, he began to see it was a plot against the Duc. Louis directed his anger at Vendôme now and Marie-Adélaïde finished him skilfully. Although he was not the ultimate favourite general anymore, he still belong to the lucky few to have access to Marly. One day, as Marie-Adélaïde sat down with her father-in-law, whose clique was the source of the lies, the Dauphin invited Vendôme to join them. The Duchesse begged the Dauphin to excuse her, for his presence at Marly was hard to deal with already and playing cards, at one table, was more than she could bear after what happened. Vendôme was about to seat himself as he was send away again. It was quite the humiliation for him. Even more so as the King heard of the matter and thus withdrew his right to appear at Marly, for it bothered the Duchesse. It did not take long, until he was not welcome at Meudon, the residence of the Dauphin, anymore either.

It made people aware that the little pretty Princesse was more than they thought she was. She clearly had the King’s ear and the King cared for more than just her amusement… but being the King’s favourite companion was not as fun as it might sound. Louis XIV could be quite uncaring. She had to go wherever he went, even when she was not feeling well or pregnant. If Louis wanted to go the Marly, Marie-Adélaïde had to go with him. In 1708 his desire for her to accompany him probably caused a miscarriage.

Marie-Adélaïde’s health was quite robust, but by then it appeared as if that was changing. In 1701, after a bath in a river, she fell ill and was thought to be at death’s door for a while. She also had bad teeth and abscesses formed frequently, which put her in a lot of pain. She had one on 1705 and Madame de Maintenon noted in a letter: “The Duchesse de Bourgogne is not well; the doctors prescribe a number of remedies which require much more patience than she is able to give. However, Monsieur Fagon does not think much of the tumour of which she is so proud, for she likes to give big names to her maladies.” Another malady followed in 1708, which Madame de Maintenon blames on exhaustion after the festivities of the carnival.

As the Dauphin died suddenly in 1711, the Duc de Bourgogne became the new Dauphin. Nobody had expected it, especially not Marie-Adélaïde, who judging by Louis XIV’s advanced age, would be the new Queen of France in a couple of years…. but she died only a couple of months after her father-in-law.

Madame de Maintenon wrote on 28 December 1711: “Our dear princess has been tortured for several days by abscesses in her teeth; but she is rather better to-day.” And on 11 January: “A few days ago she had a feverish attack; the courtiers were dismayed, and talked of the irreparable loss which her death would cause.” Versailles had a very deadly measles epidemic that winter.

On 18 January, a Monday, Louis XIV went to Marly and as always, insisted Marie-Adélaïde should go with him. As they arrived, her face was swollen and she retired to bed at once. She had to rise again in the afternoon, because Louis insisted she should join him in the salons. She did that, her face being wrapped up, and played cards, before retiring again to have supper in bed. She spent most of the following day in bed, but rose at 9 o’clock in the evening to visit the King and play cards in the salon. She felt better the next day and slowly returned to her merry self…. until 5 February, when she had a sudden attack of fever. It was gone by the morning and Marie-Adélaïde went about her daily duties. The fever returned over night and this time stronger. She remained in bed on 7 February and by 6 o’clock in the evening, she was in so much pain that she had to ask the King to postpone his planned visit.

Madame de Maintenon wrote to Madame des Ursins the very day: “The Dauphine has a fixed pain between the ear and the top of the jaw, just below the temple: the affected part is so small that you could cover it with a finger-nail; she has convulsions and cries like a woman in travail, and at about the same intervals. She was bled twice yesterday, and has had three doses of opium; a moment ago she seemed more easy. I am going to see her, and will close this letter as late as possible in order to give you the last news. … 7 p.m.—The Dauphine, after smoking and chewing tobacco, and taking a fourth dose of opium, is rather better. I have just heard that she has slept for an hour and hopes to have a good night.”

She did not have a good night and spent it in much pain until 4 o’clock in the morning, when the pain suddenly vanished. Marie-Adélaïde said the pain was worse than what she suffered during childbirth. Just as quickly as the pain vanished, the fever returned. She was unconscious for most of the day and her doctors had no clue why. By 9 February, a strange rash appeared on her skin and alarmed the doctors. They thought it might be measles… but then the rash disappeared again. The doctors remained clueless, but said it might be the best if she confessed, just in case. She did that and also received absolution and extreme unction.

Marie-Adélaïde asked for the prayers for the dying to bed read an hour later, but was told that it was not yet that serious and she should try to sleep instead. While she tried, the doctors, seven of them, had a chat about what to do next. The usual. They decided she should be bled once more, enjoy a bath in boiling hot water and take an emetic.

Neither of it helped and only weakened her further… and so, on 12 February, a Friday, after several hours of unconsciousness, Marie-Adélaïde died at 8 o’clock in the evening. While in the room below her, her husband was suffering of a fever which would reunite them again a couple of days later.

Madame de Caylus wrote to Madame des Ursins two days later: “The princess gave life to everything and charmed us all. We are still stunned by our loss, and every day we feel it more intensely. It is impossible to see the king, or even to think of him, without a feeling of despair and without constant anxiety for his health. As for my aunt (Madame de Maintenon), it is impossible for me to speak of her, except to obey her instructions. She cannot write to you, and you will easily understand why.”

Louis XIV was beside himself with grief. He loved Marie-Adélaïde and mourned her like he had once mourned his mother. Not even the death of his brother had caused him such extended grief. And with Marie-Adélaïde’s death, the golden days of Versailles were finally over. Her arrival had brought back the festivities and laughter, her death took all of it. Saint-Simon puts it best, writing: “With her, departed joy, pleasure, and every kind of grace; and darkness settled over all the Court. She had been its life, she filled it, possessed it, penetrated its inmost being; and, if it survived her, it was only to drag on a languishing existence.”