Le Palais du Louvre, Une Histoire.

I don’t know about you, but my favourite place to be in Paris is the Louvre. Not just because it is a fabulous museum now, but more because of its very walls. Just looking at this vast building and thinking about what those venerable walls have seen… if they could talk, the stories they would tell would be by far superior to all our movies and series.

Today’s Louvre stands on the remains of a fortress of the same name. This fortress was built in the 12th-century by orders of Philippe Auguste, aka Philippe II, the first French monarch to style himself King of France. There are quite a few theories as to what the name Louvre actually means, the most common one is that the place on which the Louvre was built, had the Latin name Lupara.

Today’s Louvre stands on the remains of a fortress of the same name. This fortress was built in the 12th-century by orders of Philippe Auguste, aka Philippe II, the first French monarch to style himself King of France. There are quite a few theories as to what the name Louvre actually means, the most common one is that the place on which the Louvre was built, had the Latin name Lupara.

Lupara, a derivation of lupus means wolf, and is a different term for the French louverie, and that refers to a place hosting/training men for the wolf-hunt, but it could also mean that the area had plenty of wolves back then. Either way, what is today pretty much in the centre of Paris, was back then at the outskirts. Philippe Auguste’s Louvre occupied the southwestern quarter of the current Cour Carrée and was meant to protect the right shore of the Seine.

Philippe Auguste wanted to reinforce the defences of Paris and for that, he created what is called the enceinte de Philippe Auguste. He was in a struggle with the House of Plantagenet, who held the Duchy of Normandy, and planned to go on a crusade soon, so to keep Paris save while he was away, he ordered a large wall to be built around the city. (You can still behold parts of that wall when visiting Paris today.) His Louvre was build in the spot the Plantagenet’s would probably come from and faced Normandy. This spot also happened to be the most vulnerable one, thus building a fortress there made utter sense. Since it was meant for defence, it wasn’t a pretty building at all. It was a large keep, with a high tower, a dungeon, and smaller towers at the sides, two drawbridges over a dry moat, one to the south and the other to the east.

Philippe Auguste died in 1223 and was succeeded by Louis VIII, who died three years later. Then it was the time of Louis IX, or Saint Louis as he is called, and he decided to add a bit more life to the fortress. He ordered some rooms to be added, which had no defensive purpose, and transferred the royal treasury to the Louvre. Yet the Louvre did not become a royal residence until many years later.

Five King’s later, it was Charles IV’s, who was called the fair in France and the bald in Navarre, turn to rule France. By then Paris had grown quite a bit and the Louvre was no longer outside of the city, as it has been when it was built. Having successfully fought down a revolt, Charles had new ramparts created around the city and turned the Louvre into a residence, but without diminishing its defence qualities. The Louvre gained apartments for the King and Queen, several towers, a very innovative spiral staircase, gardens, and a great hall for feasts.

Another two Kings later, during the rule of Charles V, the Louvre gained a library. Charles V, called the wise, was a lover of the arts and had a vast collection of books. He moved a part of them to what was called the tour de la Fauconnerie, a tower in the north-west of the building. By 1373, the tower hosted 973 richly adorned manuscripts over three stories. Charles V liked the Louvre, his successors did not so much.

The fortress was not inhibited for a long time after Charles V died. Another five Kings later, France was taken by a new spirit, the Renaissance, and the Louvre received a complete revamp. The King, François I, returned from Spanish imprisonment to Paris. By then, the Louvre was commonly viewed as a seat of royal authority by the people and its name even appeared in the oath of allegiance to the King. The Hundred Years War had taken its tool on the by then already quite ancient building, as François I decided to make it one of his residences. The birth of the New Louvre.

Over the course of the next decades, the Old Louvre vanished bit by bit and was replaced with a Renaissance style palace, to which every King that followed added their mark in form of their initials. (I really love to wander about in the Louvre and look for the royal monograms. I find it amazing how many there are and how you can walk through the centuries by going from a François I room to a Henri II to a Henri IV to a Louis XIV.)

François I started by having the old central dungeon demolished and clearing the courtyard, by moving all its buildings, like kitchens, outside of the walls. Pierre Lescot, after whom the Lescot Wing is named, was hired to create the first parts of this New Louvre, a large hôtel particulier and ceremonial rooms. Meanwhile, François I acquired what is today the Louvre’s best known treasure: the French call her La Joconde, the Italians La Gioconda, for the rest of the world she is the mysterious Mona Lisa.

It was believed that the dungeon of the Louvre had been completely destroyed, but in the 19th century it was discovered that this was not the case. The stones of the dungeon and two of the four walls, were taken down and used to fill the moat. Later on, the base of those walls was cleared, during which many objects dating back to their creation were found. All of it, the walls and the objects, are now accessible to the public in a collection named Medieval Louvre at the Salle Saint-Louis.

The demise of François I halted the construction of the Louvre for a moment. The work was taken back up under his successor Henri II, who altered the plans for the palace a little. The west wing of the old building was demolished and a new elaborate wing created in its stead. As the first floor was just about to be finished, Henri decided a large reception room was needed, thus the plans had to be redone. This reception room took up the space meant for a majestic staircase, which had to be relocated to the northern end of the wing. (It’s known as the Escalier Henri II.) With the space freed up, a 600 m2 room was created that is still as impressive today as it was back then.

The room received the name Salle des Caryatides, after the four huge statues, carved by Jean Goujon, which hold a balcony for musicians. Opposite of them, on the south side, was an elevation, which marked the King’s place. Back then, the room was used for fetes and as a guard-room. Under Louis XIV, it was used for the same functions, but sometimes also the location for the toucher des malades par le roi. A ceremony during which the King touched, and healed, people suffering of scrofula. In 1658, Molière and his troupe were invited to perform in front of the King in the Salle des Caryatides. It was a first time, for both, Louis XIV and Molière. Today the Salle des Caryatides hosts Roman copies of lost Greek works.

By the time the wing was finished, it had three floors. The ground floor hosted the Salle des Caryatides, the first floor had a room for the royal guards, where the tradition of public meals became a thing, the third floor had residential functions and hosted higher ranking servants and the Queen’s ladies. The design of the Lescot Wing, became the base for further extensions and the style of its decorated walls was copied for those.

Of course, a royal residence does need a proper apartment for the King. Henri II asked Lescot build an extension for the purpose, thus called Pavillon du Roi. Four stories high, it hosted a council room on the first floor and the King’s apartment on the second floor. Henri II’s bedroom, which was after him occupied by many other Kings, including Louis XIV, received a new style of ceiling. Instead of the usual beamed style, it had a beautiful and rather impressing carved ceiling. (The woodwork of those rooms was later dismantled and put into different rooms. So, today’s Chambre de parade du roi and Chambre à alcôve, in which Louis XIV slept as a child, are not where they used to be back in the days. You should still make sure to go there, if you visit the Louvre, the air is usually terrible there, for whatever reason, but the wood carvings are fabulous.)

Henri II, of course, also wanted his wife, Catherine de Médicis, to have a new apartment and thus Lescot was asked to create a south wing as well. Henri did not see the work finished. Henri II died in 1559 and was succeeded by his son François II, who only ruled France for a year before dying in 1560 at the age of sixteen. His brother Charles, as Charles IX, followed him on the throne.

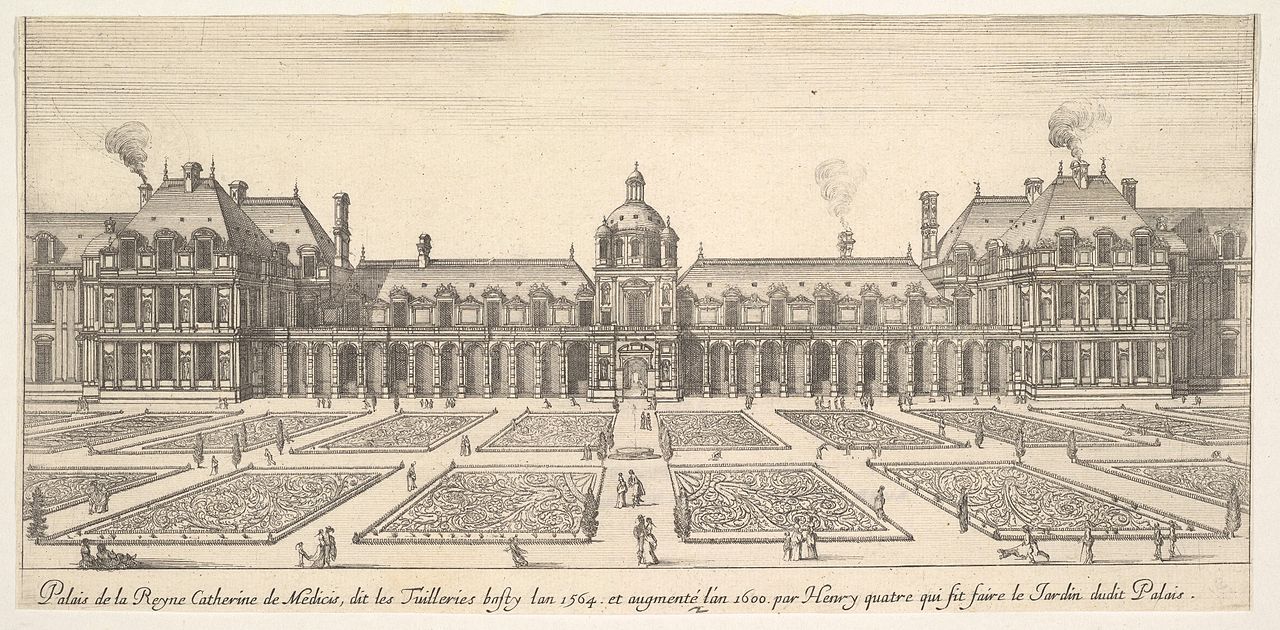

Meanwhile, the work of the south wing commenced. Lescot demolished the old wing and copied the design of the wing he had just finished for the new one, with the intention to create a four-sided château with an identical third wing to the north and a lower, entrance wing, on the east. The former moat was covered with a terrace to allow access to the garden between the south wing and the Seine and a gallery, called the Petite Galerie, was added and spread from the southwest corner of the Louvre to the Seine. The work at the Louvre became less important to the woman in charge, Catherine de Médicis, with the creation of the Palais des Tuileries on the opposite side of the Louvre… and then the Wars of Religion happened.

Towards the late 1560’s, all work at the Louvre was stopped, for France was at war with itself. During this time, the Louvre, a mix of medieval fortress and Renaissance palace, served as Parisian residence of the royal family and it became a bit of a gloomy place. It was the embodiment of royal power and intrigues, with Catherine de Médicis as the puppet master. The Louvre saw a grand wedding, that of Henri de Navarre and Marguerite de Valois, which was followed by a great bloodbath that coloured the old walls red. Henri de Navarre escaped by fleeing to the rooms of his wife, past corpses that lined the streets.

After the death of Charles IX, his brother Henri, as Henri III, placed himself on the throne of France. He did not undertake any major works at the Louvre, but he turned it into a place for festivities and the official main residence of the King, which the Louvre would remain until Louis XIV moved the seat of power to Versailles. Henri III’s reign was short and the Kingdom still at war. Henri de Navarre became his successor as Henri IV, after Henri III was assassinated at Saint-Cloud.

Henri IV had quite the task ahead of him. The Kingdom was ruined and unstable, it were dangerous times. He had to establish his rule and what better place for that then the old Louvre? Building work boosts the economy and appeases. If the King has time to build, things can’t be that bad… and Henri had something special in mind for the Louvre. The Grand Dessein, as it is called, involved the demolition of what was left of the Old Louvre, the construction of a large courtyard, a wing to connect the Louvre to the Tuileries, the conclusion of the work at the Petite Galerie, and the remodelling of the areas surrounding the Louvre.

The most prestigious project of those was certainly the creation of the connection between the Louvre and the Tuileries. Back then it was called the Galerie du bord de l’eau, a bit later people started to simply called it the Grande Galerie and that is still what we call it today. It was a huge undertaking. This wing measures 450 metres in length and is 13 metres wide. For comparison, Louis XIV’s Hall of Mirrors, which looks huge, is 73 metres long…

Two architects carried out the work: Louis Métezeau did the part between the Petite Galerie and the enclosure of Charles V; Jacques II Androuet du Cerceau did the remaining part. The base was done by 1600, but was a mere shell and lacked decor. The decorations were done later on under Louis XIII. This Grande Galerie was not only built to look nice and impressive, the ground floor hosted shops, the mezzanine hosted accommodations for artists, and most important of all, since Paris was a dangerous place, this connection was a way for Henri IV and his family to move between the two palaces unseen. In case of emergency, which was not unlikely, the royal family could flee from the Louvre to the Tuileries, or vice versa, and board a carriage to safety.

Meanwhile, the Petite Galerie was finished and a new floor added to it to host paintings of all Kings and Queens of France. Where the Petite Galerie met the Grande Galerie, a pavilion was added as well…. but then le Bon Roi Henri died. He was assassinated on a street pretty much next to the Louvre. All building work was stopped, the northern and eastern parts of the Old Louvre remained in place, and the Grand Dessein unfinished.

Louis XIII, still a child, took over the crown under the Regency of his mother, Marie de Médicis. Not much was done at the Louvre itself under the Regency, but once Louis XIII decided to take up the plans of his father, the Louvre turned construction side again. The Grand Dessein, as Henri IV had in mind, proved difficult to execute, so it was altered a little. And now, the old northern part of the Louvre was taken down as well to make space for a new wing, in Lescot style and perfect symmetry. While all that happened, parts of the Old Louvre are renovated as well and work on the Cour Carrée began. North of the Lescot wing, a new pavilion, today called Pavillon de l’Horloge, was raised into the air and the Henri II staircase was enlarged. The famous Grande Galerie was a construction side as well, with decor being added… and occasionally, when it rained, Louis XIII could be seen walking his pet Camel in the Grande Galerie.

As Louis XIV was born, the Louvre was already very ancient. It was still a mix of fortress and palace, with elaborate wings bordering on old medieval towers. The parts of the Old Louvre, those that had not been taken down yet, had already seen 400 years of history, some of the newer parts had already seen 200 years.

Although there was a great influx of Italian artists during the Regency of Anne d’Autriche, no major work was done at the Louvre until Louis XIV came of age. Louis XIV never liked the Louvre too much…. and Paris in general. He found the Louvre too dark, too depressing, too old, not fitting his persona… too many people had left their marks there. But it happened to be the seat of power. Thus, starting in 1652 new apartments for Anne d’Autriche and also for Cardinal Mazarin were created. The Queen Mother got a splendid summer apartment beneath the Petite Galerie and the apartment of the young King was enlarged to reach the Petite Galerie. Louis Le Vau added a chapel, in which, years later, Bossuet, during a series of Lenten sermons, scolded the King for his merry-making with a certain young lady and got him into quite a huff for a moment.

Henri IV’s Grand Dessein was not forgotten by Louis XIV either. By 1657, it was discussed to take the plans back up. Much to the displeasure of the King’s uncle, Gaston de France, because the plans meant that the Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon, behind the Louvre, would have to go in order to make space for new wings. The protest was in vain. The crown started to purchase properties in the immediate neighbourhood and demolished it all, as well as the old kitchens of the Louvre.

The architect Louis Le Vau and painter Charles Le Brun took up work in 1659. The first oversaw a revamp of the Tuileries, the latter worked on the completion of the north wing and a revamp of the Pavillon du Roi…. and then a fire broke out. It started in the Petite Galerie, caused by careless workers preparing the room for an entertainment, and once it was put out, much of the Petite Galerie and adjoining rooms were in ruins. Cardinal Mazarin, by then an old and weak man close to death, only narrowly escaped the fire. Servants had to carry him out of his rooms, which bordered the Petite Galerie, and inhaling all that smoke damaged his lungs badly. Work to reconstruct what the fire had destroyed was taken up at once, and while at it, the Louvre gained another marvel, the Galerie d’Apollon.

Le Vau reconstructed the Petite Galerie, doubled its height, and Charles Le Brun gave new decorations dedicated to the God Apollo and to create a link between the Pavillon du Roi, this new Galerie d’Apollon and the Cour Carrée, the Rotonde d’Apollon was added to serve as a reception room for Louis XIV. (The first time I set foot into this small round room, I did not know its purpose. It was full of tourists standing around, there was a constant coming and going from the connected Galerie d’Apollon, it was quite loud there. I looked up at the cracks in the ceiling and I had this strange feeling of… I don’t know. I just wanted to stay in that room for some reason. It was strange. It was not awe or something like that. I just had the feeling this little room was important and that I should stay there.)

To the west of the new Galerie d’Apollon, seven rooms, called the Cabinet du Roi, were added and hosted from 1673 on parts of the King’s art collection. The rooms were then turned into a sort of small art gallery and accessible to some chosen members of the public. The world’s first ever art exhibition took place at the Louvre under Louis XIV as well, but that already in April 1667. The event was hosted by the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture and Louis XIV liked it so much, that he ordered one should take place every year.

The Sun King lost interest in the Louvre as he developed his Dream Of Versailles, but it did not stop the construction work at the Louvre… although Louis was a bit reluctant at times, especially when his ministers suggested he should forget about Versailles and put all the money into the Louvre instead, already for the sake of tradition and to add his mark. He did add his mark to the Louvre, but he did not like it that much. Louis did not want to be one of many, what he wanted was to create something new, something better, and that something was Versailles. At least for Colbert, the Louvre remained to be of utmost importance. The work at the Cour Carrée must be continued and the Louvre needed a stylish east facade.

The most important addition to the Louvre during the time of Louis XIV was the Colonnade du Louvre, which is celebrated as the foremost masterpiece of French Architectural Classicism to this day. It was designed by Claude Perrault, who won a competition held by Louis XIV to find the perfect design for the Louvre’s new eastern facade. Perrault won this competition against the great Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who had gone through the troubles of travelling from Rome to Paris especially for it, but whose design was considered to be too Italian. In contrary to the rest of the Louvre’s facades, this one looks very different and on first glance, one might not realise it is actually part of the Louvre.

But then, after adding his mark, Louis XIV lost the last bit of interest he had in the Louvre. It was all about Versailles now. Thus the Louvre was abandoned as residence and left almost deserted. The idea to finish the Grand Dessein was dismissed as well, the Cour Carrée remained unfinished and the brand new colonnade was left sans roof. Most of the grand hôtels, those that were still there and had not been demolished to make space for the colonnade, were deserted along with the Louvre. The nobility settled in new hôtels in Versailles.

Already before the court moved to Versailles, Louis had a slight aversion to stay in the Louvre. He rather resided in the Tuileries then, which were brighter and opened into a large garden. Since it would be a bit of a shame to waste all the space of the Louvre by simply leaving it empty, Louis, already in 1672, allowed the Académie française to move in. The Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture moved in too, followed by that of architecture, which settled in the Queen’s apartment. By 1697, the Académie de politique moved in as well as the Académie des sciences. On top of it, where once Kings and Queens lived, artists are now allowed, free of charge, to occupy rooms and live there. All of that led to the Louvre losing its sparkle and to a slow deterioration of the structure…. some of the rooms were in horrible states, because the people living there did not take care of their surroundings. As Voltaire put it: Louvre, palais pompeux dont la France s’honore, Sois digne de Louis, ton maître et ton appui. Sors de l’état honteux où l’univers t’abhorreEt dans tout ton éclat montre-toi: comme lui.

He wasn’t the only one to criticise the state of the Louvre and after the death of Louis XIV, more and more people did it. Louis XV did care even less for the Louvre than Louis XIV did, but also he added his mark. Tackling the Grand Dessein was out of the question, but at least the Cour Carrée was cleared from the parasitic constructions and the persons occupying those and its design was finally finished. Some work happened at the colonnade as well, it was still mostly sans roof, but one could behold it better now after the demolition of what was still left of the Petit-Bourbon. By then, the colonnade was in dire need of renovation already and rusty metal bars, which coloured the stones, had to be replaced. A bit later, it finally received a proper second floor.

He wasn’t the only one to criticise the state of the Louvre and after the death of Louis XIV, more and more people did it. Louis XV did care even less for the Louvre than Louis XIV did, but also he added his mark. Tackling the Grand Dessein was out of the question, but at least the Cour Carrée was cleared from the parasitic constructions and the persons occupying those and its design was finally finished. Some work happened at the colonnade as well, it was still mostly sans roof, but one could behold it better now after the demolition of what was still left of the Petit-Bourbon. By then, the colonnade was in dire need of renovation already and rusty metal bars, which coloured the stones, had to be replaced. A bit later, it finally received a proper second floor.

Unlike other royal residences, like Tuileries, the Louvre was spared during the Revolution. It had by then almost completely lost its royal sparkle and the people did not really associate it with royal authority any longer… but what to do with it? Towards the end of the 18th century, the idea emerged to turn the palace into a museum for the people.

The Louvre as museum exists since 10 August 1793, the first anniversary of Louis XVI’s arrest. The general public was free to access the Louvre to behold parts of the royal collection and pieces of art confiscated on three days a week. The collection showcased 537 paintings and 184 objects of art, of with three-quarters were from the royal collection and the rest former Church property. The collection expanded by revolutionary armies carrying pieces of art, like from the Vatican, back to France and seized property previously owned by nobles or the crown. Nothing of it was really marked or arranged in orderly fashion, so it was quite the mess and the first museum only lasted for three years. It opened again in 1801, this time in a more orderly fashion and better lighting.

Then came Napoleon… and he brought a lot of art objects home from wherever he went to conquer, especially from Italy. The Louvre museum was renamed Musée Napoléon and its collection grew in size by the day. That proved to be quite the problem later on, for after Napoleon was defeated, every nation started to demand the Louvre should return to them what Napoleon stole. Some pieces were returned, some were quickly hidden, some were bought and for some a settlement with the previous owner was concluded.

What Napoleon also did, was to take up the Grand Dessein. The Louvre turned construction side again, the facades were prettied up, renovations carried out, floors were replaced, decorations completed or replaced by new ones, a new staircase was created, roofs were replaced and repaired, ceilings painted, new rooms added and most importantly, it was decided to finally do what Henri IV had in mind. To connect the Louvre to the Tuileries, not just on one side, but on both sides to create one huge palace with one huge square in the centre. For that, pretty much everything between the Louvre and the Tuileries was taken down, including a whole church. Work started to create the connection wing, along the Rue de Rivoli, but was stopped by the fall of the Empire.

Now it was the time of the Restoration, a glorious time for monarchist. The Bourbons took back their crown and wanted to return the royal sparkle to the Louvre by means of interior design, but also the wing Napoleon started is completed along with its decorations. Just in time, for the Restoration did not last long.

The Second Republic rose, and decided to carry on the completion of the Grand Dessein. Funds were given for the restoration and completion of the Galerie d’Apollon, the Salon Carré, the Grande Galérie, and new artwork was added, around 20.000 pieces. The Louvre was by then connected on both sides to the Tuileries, like Henri IV had in mind a good 300 years earlier. The parts of the Old Louvre, buried underground under new structures, were 600 years old, the new structures, some of them 400 years old, reflected, and still do today, the changing and often chaotic times that had passed.

What came next, was quite chaotic too. In 1871, during the time of the Paris Commune, the Louvre was badly damaged by a fire. This fire was started by a certain Jules Bergeret, who set the Tuileries aflame. The Palais burned for a good forty-eight hours and was left in ruins. Luckily, much of the furniture and art had been previously removed from the building. The fire then spread towards the Louvre, via the north wing, and destroyed the library and several of the adjoining rooms and corridors. Luckily as well, the Parisian firemen managed to save the rest of the Louvre in a seemingly endless struggle against the flames, which they eventually won.

The Tuileries, a mere shell then, remained standing until, twelve years later, it was decided to tear the ruins down… and that was the end of the Grand Dessein. (There is a group of people, the Comité national pour la reconstruction des Tuileries, seeking the recreation of the Tuileries to be used as museum. A lot of the furniture of the Tuileries still exists and could be put back in place then.)

The dawn of the 20st century… and two wars. By the time World War II started, the Louvre’s collection had grown a lot and was home to some of the most important and expensive pieces of art. The administration of the Louvre feared that Germany, who had carried off a lot of art already from other places, would destroy the collection. Thus, at the start of the war the most important paintings were brought away to be hidden all over France. Some time later, they were joined by other important pieces and within some months, between August and December 1939, the Louvre was almost completely cleared of the whole collection. With just the pieces that were too fragile or heavy to transport being left in place along with paintings, placed in the basement, which were considered to be not that important. By the end of 1945, most of the collection was back in place again. (Did you know that Hitler wanted to destroy all of Paris? I mean all of it. The whole city. He wanted to blow it up. That plan was stopped pretty much last minute.)

The Louvre, as you might have noticed, is ever-changing. Each period added this or that… our period added a new and very controversial new entrance. Under François Mitterrand, the Louvre was turned fully into a museum. By then, the original entrance could not deal with all the people seeking to behold the Louvre’s collection anymore. A new entrance was needed… some call it a pimple on the face of Paris, some call it sacrilegious, others a disgrace, I usually call it that thing, but officially it is called the Pyramide du Louvre. The controversy is mainly about the pyramid being a pyramid, in a modern style, which does not at all fit the Renaissance style of the Louvre. Plus a pyramid is a symbol of death and the execution of the whole thing, people say, is quite immodest and pretentious. Also, a bit of an insult to the long history of the Louvre.

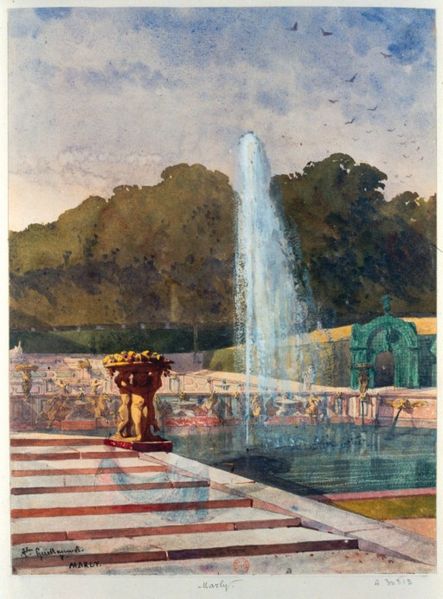

Last, but not least, as a Louis XIV fan, which I presume you are if you found your way here, the Louvre might not be on top of your Louis XIV sightseeing tour when going to France. I think Versailles and Vaux will lead the list, but go to the Louvre. Many people have no clue how much Louis XIV there is, but there is loads. The Louvre hosts the so-called Louis XIV rooms with many items from the time of the Sun King, which were owned by him, part of his collection, or owned by his family. Then there is a whole department in which rooms of different styles have been recreated, among that the Louis XIV style. (For Monsieur fans, there are items from Saint-Cloud there too.) There are many objects from Marly at the Louvre too.

Then you can behold the room, although relocated, in which he once slept before really becoming the Sun King and the fabulous Galerie d’Apollon. Go there, imagine all those noisy tourists are courtiers and how calls of le Roi! echo through the halls as the King makes his way to the Galerie or how he promenades the length of the Grande Galerie with the ladies…

When you go to the Louvre, make sure to get your tickets in advance. (You can also get a museum pass, which grants to entry to Versailles, the Louvre, Vaux and various other places.) Entry is not too expensive and tickets can be bought via the Louvre website and printed at home. When you enter the Louvre via that thing, you have two lines. One for people sans tickets, one for people with tickets. The sans ticket line can be very long depending on the day. If you already have a ticket, you only have to wait a few minutes to get inside instead of waiting an hour. If you don’t have a ticket in advance, prepare for a long wait… tickets can be then bought at a special section of the underground foyer and there is quite to queue too. In the foyer, you can also get floor plans, in various languages, for free and from there you can reach various restaurants. Louvre breakfast is the best of breakfasts….