Philippe de France, frère unique du roi

When Louis XIV was born in 1638, it was regarded as a miracle. No-one really thought Louis XIII and Anne d’Autriche, a old woman by the standards of the time, were capable of producing a healthy heir. To everyone’s surprise, both also managed to produce a spare.

Philippe de France was born on September 21 in 1640 at the old part of the château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, just west of Paris, at around ten o’clock in the evening. Nine months earlier, on Christmas 1639, Louis XIII had uttered the very unusual desire to spent the whole night in the company of his wife. Philippe was the result.

La joie renouvelée par l’heureuse naissance d’un second fils de France, qui est à prèsent Monseigneur le Duc d’Anjou, a Sainet Germain en Laye, le 21 September 1640. – le Ceremonial François

The happy news did not take long to cross the few kilometres to Paris and the following celebrations were huge. Paris erupted in joy, the guns of the Bastille and Arsenal were fired to welcome the new Son of France, the bells of the Palais-Royal rang and a Te Deum was celebrated in the venerable Notre-Dame Cathedral. Just like during the celebrations of Louis XIV’s birth, the Parisians danced on the streets and lit bonfires.

Upon his birth, Philippe received the title Duc d’Anjou, and was the second in line to the throne, staying so until the birth of le Grand Dauphin in 1661. Louis XIII did consider making his second son Comte de Artois instead of Duc d’Anjou, in celebration of war victories, but then decided to go with d’Anjou.

Petit Monsieur, as he was also called during the lifetime of his uncle Gaston, who held the title Duc d’Orléans as brother of Louis XIII, was baptised in private one hour after his birth by the Bishop of Meaux and shortly after, presented to the court in his brand new apartment. As common for royal children, Philippe got his own nursery, household and physician, maids and valets. He shared a governess, the Marquise de Lansac, with his brother and had an assistant-governess, but only had one wet-nurse, while Louis had two at his disposal.

Little Philippe did not have much of a chance to get to know his father. In his first few years, he was mostly surrounded by members of his household who looked after his well-being as if he was France’s greatest treasure. He probably saw more of his mother Anne d’Autriche than of his father and as little Philippe was not yet two and a half years old, his father passed away on the thirty-third anniversary of his own father’s death. How much Philippe actually noticed concerning the demise of his father, and whether he received more than a blessing from him on the death bed is unclear, but Philippe’s signature, as Duc d’Anjou, can be found along with that of his mother, brother and uncle on the death certificate of Louis XIII, signed on the day of Louis le Juste’s demise.

From then on it was only Philippe, Louis and Anne. Philippe was now the brother of the King of France and being the King’s brother was not an easy thing to be. Although Philippe was the heir to his four-year old brother, shared one blood with him, he was and never would be on the same level as Louis. Something that is probably hard to understand for a little boy. In matters of rank, he was above everyone else, but below his brother. In matters of attention, Louis – as King – of course got a bit more of it. In matters of care, Philippe again got a bit less… but this is just how society worked. Royal children could not be brought up as equals, for the simple reason that the first-born had the right of inheritance, and if brought up as equals, other siblings might challenge the first-born. And Louis was the first-born by the grace of God – God had granted him life and God had granted him to be King…. and so Petit Monsieur grew up in the shadow of his older brother and was taught to be less than him. Of one blood, but forever one step below.

Like Louis, Philippe spent his first years in the company of women. It was common for little boys to stay with the females until a certain age, referred to as breeching. Like Louis, Philippe was also dressed in gowns during this time, something that was common as well. Both girls and boys wore them, but the boys’ gowns were a little less elaborate. The reason for boys wearing gowns is quite simple, they could not yet deal with the ties and buttons on breeches if a need to release the bladder grew. Gowns come in way more handy in this case. By the age of six or seven, when they could deal with opening and closing of their breeches, the boys left the company of women and entered the company of men, their tutors. This transition from gowns to breeches also meant they were now old enough to be schooled and educated and were not longer regarded as toddlers. (If you see a painting in which Philippe wears a gown and Louis is in breeches, it just means that Louis, as the elder boy, has already been breeched. It does not mean that Philippe was dressed like that by Anne to make him feminine. Every little boy wore gowns until a certain age and not just in France.)

As Philippe’s time came to leave the company of women and join that of the men, the matter of his education and schooling was again, less compared to Louis’. Philippe’s continuing lesson, next to reading, writing, a bit a math and Latin, dancing and fencing, was to be less than his brother. By now Philippe had already witnessed several times how the people cheered little Louis and although they also adored him, they were not as enthusiastic in cheering. When both brothers rolled through the Parisian streets in a carriage with their mother, Philippe heard the shouts of vive le roi, saw the people wave at them, lift their hats, all for his brother. When both brothers played together, Philippe was the one who had to give in. Under no circumstances could he outshine the King. Louis was a quiet child and he was aware at an early age that everything he said could make someone happy or unhappy. Philippe was the total opposite.

While Louis preferred to listen, Philippe chattered like a market-woman. He loved to have his fine manner of speech admired, how finely he phrased his sentences, the big words he used… and the people loved it. They loved the little boy with the rosy cheeks and round mouth, the dark curls and lively eyes. Here again, Philippe was reminded that he was only the second born. Whenever the people loved him a bit more than they were supposed to, Philippe was left behind on the next occasion in order to not steal the attention and admiration his brother should receive. What about Louis? It is hard to say what little Louis thought of his brother. He certainly loved him and judging by letters he wrote to Philippe and signed with papa, he probably saw himself as a father figure for his little brother, who never really had one.

Philippe was a bit small for his age, but quite healthy. He had the occasional cold and fever as a child, which was nothing too serious, but in Autumn of 1647 he caught the measles. His condition was critical: along with the measles he also had a serious case of dysentery, which led to de-hydration. During this time Philippe remained in the care of his attendants in Paris, while his mother took Louis to Fontainebleau for a change of air. Whenever Louis got ill, Anne hardly ever left his side. In the case of Philippe, Anne only returned to Paris as Philippe’s condition worsened and left again as soon as he got a little better. By the time Philippe was cured, Anne found him so pale and thin that it was hard to recognise him. One year later, as the Fronde was in full swing, Philippe fell ill with smallpox and was left alone again in Paris… with a violent mob knocking at the gates of the Palais-Royal. However, this does not mean that Anne did not love her second born. She was forced to keep the show going and Louis out of danger during this time.

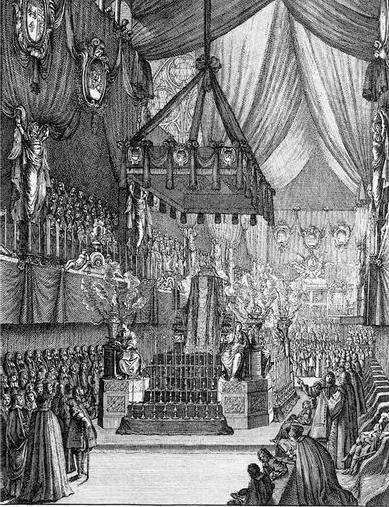

On May 11, 1648, when Philippe was eight years old, it was time for his official baptism. The elaborate ceremony took place in the chapel of the Palais-Royal at around three o’clock in the afternoon under the observant eyes of the court. For Philippe it did not only mean he was not a small child anymore, but also that he had to perform his duties towards his brother and play his role at public events. The ceremony was rather long and most children would probably have found it rather boring, but not Philippe. It was the first time he was the centre of attention. He had been carefully coached to say the right words at the right time and performed flawlessly. His uncle Gaston and aunt Henriette, wife of Charles I, acted as godparents. Philippe might have felt a little like he was King then. After all, the ceremony involved being seated elevated and anointed in Holy Oil. ‘Oh, how beautiful he is,‘ was the echo he received from the ladies of the court.

In December the following year, Petit Monsieur and his kingly brother received Confirmation together, the rite at which a baptised person, especially one baptised as an infant, affirms their Christian belief and is admitted as a full member of the church. These kind of religious services were nothing new to Philippe, as he participated in several of them as a child. When he did not spend time with his tutors or played, he went to various religious services with his mother and brother. On top of that, Philippe also heard Mass in private every day. These religious services with their glittering gold accessories, the rich brocade outfits, and this unearthly air seem to have impressed him quite a bit. Although, like his brother, he led no pious life, he always kept participating in these services and developed a great love for ceremony.

César de Choiseul was chosen by Cardinal Mazarin, who was responsible for the education of the brothers, to be the governor of Petit Monsieur. He was a man of great bravery and military glory, which turned out to be a bit of a problem. Instead of taking care of Philippe, Choiseul was kept busy by the various skirmishes of the Fronde and was not really fully available until 1653, four years after he had been appointed. But Philippe was not left without a governor: it was custom to have two assistant-governors, both high-ranking officers. While Choiseul was not available, Philippe was placed in the care of Louis’ governor… and it appears Philippe was not really encouraged to learn much during this time. If Philippe wanted to play instead of learning, he was allowed to go bouncing off. As a child, Philippe seems to have preferred the company of females, because even though he played often with his brother, he was forced to let Louis win all the time. Of course, Philippe didn’t really enjoy that, so he turned to the females. In company of men, especially when his brother was involved, Petit Monsieur was always second. While in company of women, he was the one who was adored. They told him how pretty he was, how charming, how funny, read him stories and allowed him all sorts of ‘idle’ play. Thus, Philippe’s education did not really start until the Fronde had ended.

How the Fronde affected Philippe is hard to say. He had a violent mob knocking at the Palais gates and he certainly noticed how that mob returned to check if his brother was present. He also noticed the tension around him and how he and his family were pretty much prisoners in Paris for a while. He was dragged along from chateau to chateau, woken in the middle of the night in order to change location and perhaps he even woke up some mornings to find that his mother and brother had left during the night. The valet Dubois relates what took place one evening in the Palais-Royal as barricades went up outside. Louis XIV was a mere ten years old then and did his very best to calm his brother. “The little Monsieur Duc d’Anjou was terrified. The King did his best to reassure him, even going so far as to draw his small sword, which he did with admirable grace. He caressed his trembling younger brother, keeping him by his side, saying all sorts of comforting things to him and behaving just as calmly as a great general might do, when in the face of a sudden alarming situation, he makes a speech to encourage those around him. Afterwards he was good enough to go with Monsieur to his room and put him to bed himself.”

When Choiseul finally took up his post, Philippe had already missed out on a lot of things he was supposed to know by then. Choiseul reported Philippe’s progress to Cardinal Mazarin each day and in turn was instructed by Mazarin what should be on the schedule next. Mostly piety and what respect he had to show his brother, adding that true greatness meant to be in the good graces of Louis. “Brothers of Kings cannot have too much greatness of soul, nobility of sentiment, or elevation of view, but all of these must be subordinated to what they are duty bound to owe their sovereigns, for even while being their brothers, they do not cease to be their subjects” was one of the lessons Philippe received, according to Choiseul. The governor was not always fond of the instructions he received. He did agree that Philippe must be taught to submit to his brother – the Fronde had just showed why – but was not too happy with the fact that Philippe was left behind so often, when Louis was already taking part in council.

It is no surprise that Mazarin was accused of neglecting the education of his charges. Rumour spread that the Cardinal kept the King in ignorance about many things, so he could govern Louis longer. In the case of Philippe, it was said the Cardinal kept him unlearned, so he may not outshine his brother. If Louis’ education was lacking, as he said himself, that of Philippe must have lacked even more. Philippe was certainly smart enough to learn if he wanted – he was able to remember the family trees of all noble houses, all rules of etiquette, who had what privilege, etc. Languages seem not have to been on Philippe’s schedule, but he was somewhat fluent in Spanish, thanks to his mother. It also seems that Philippe preferred the spoken word over the written one. He did learn to write, but did not really enjoy doing it, and mostly kept his letters quite short. He also never learned how to write gracefully and his handwriting was not always easy to decipher, even for himself. As his second wife reports, he often came to her in order to ask what he had written in this or that letter, because he could not decipher his own writing.

Reading was something he was not really into either, at least in regards to classic literature. As an adult, he was once admired for studying his prayer book during mass, but it turned out he was actually reading some cheeky poems. Politics also played no part in Philippe’s education. That was reserved for Louis. Physical activity, however, was. Petit Monsieur was taught how to ride, fence and dance. The latter he did with passion, the first he did very well, but with not much interest. Philippe was also taken to hunt with his brother and enjoyed swimming in the Seine with him. The little miniature fort Mazarin had built for Louis in the Palais was familiar to Philippe as well. Both brothers attacked and defended it often against other noble children. At least, when being in his brother’s team he was allowed to win. What a strange situation it must have been for him – always second to his brother, yet above everyone else. Petit Monsieur was aware of it. From his childhood onwards he always paid great attention to what was his due.

Philippe had a love of the arts and pretty things, which might be due to Mazarin. The Cardinal had a vast collection of art and bling himself, which Philippe without a doubt admired from time to time. Those things were by far more interesting than silly old books…. Mazarin noticed Petit Monsieur’s passion for them too and thus, whenever little Philippe rebelled, a little shiny gift was delivered to him in order to shut him up. Louis carried on this reward system after Mazarin’s demise. Hosting gatherings was also something Philippe was fond of. Due to their social position, both brothers were encouraged to host small get-togethers for the court and the other noble kids. Philippe loved it and did his job as host very well.

Philippe had a love of the arts and pretty things, which might be due to Mazarin. The Cardinal had a vast collection of art and bling himself, which Philippe without a doubt admired from time to time. Those things were by far more interesting than silly old books…. Mazarin noticed Petit Monsieur’s passion for them too and thus, whenever little Philippe rebelled, a little shiny gift was delivered to him in order to shut him up. Louis carried on this reward system after Mazarin’s demise. Hosting gatherings was also something Philippe was fond of. Due to their social position, both brothers were encouraged to host small get-togethers for the court and the other noble kids. Philippe loved it and did his job as host very well.

With the Fronde over, a new chapter in Philippe’s life started. He was no longer a child, was aware of what was due to him and told over and over the role he had to play regarding his brother. Now he was set up in an independent household, as was custom. Louis and Anne resided in the Louvre, Philippe in the Tuileries. Although both residences are pretty much on the other side of the street, Philippe might have felt rather alone now. He was hardly in the company of his mother and brother anymore, unless in public services. Also the two relatives he liked the best were no longer in Paris. Those were his uncle Gaston, who shared the same fate as King’s brother with Philippe, and Gaston’s daughter, La Grande Mademoiselle.

After establishing of his own household, Petit Monsieur had to play his part in the coronation of his brother. His part? To display to all how he was the first subject of his brother. As tradition required, Philippe swore never-ending loyalty, kissed the feet of his brother and accompanied him afterwards. Of course, while Philippe played his role well in public, he was not always happy with it in private. The little Duc d’Anjou had gained a bit of a reputation as a hothead already. It did not happen often, but when he lost his temper, it was difficult to calm him. Philippe was most likely aware that punishment followed outbursts, but he had his limits. One time he slapped a lady of his mother, because that lady dared to laugh as he tripped over the skirts of his dancing partner. Another time, he slapped the daughter of another lady, who had dared to get cheeky with his nurse. Louis was not safe from the occasional outburst either. They argued, they fought, they ripped each others beds apart and even fought over a bowl of broth. Compared to Louis, Philippe was still a little childish. He still liked the company of the females and to giggle and gossip with them. As boys do, especially during puberty, where one tries to deal with the growing of hairs in places and the new strange feelings in the groin area, when one is influenced by what others do and has not really found to oneself, Philippe also played little tricks on the girls. He found it very funny to try and lift their skirts and make remarks about what was underneath. Anne did not find it funny. At all. She ordered a good whipping for Philippe. But while Philippe had to endure it in the past, now he was a teen. No longer a child. So when the whipping was attempted, Philippe said that if anyone tried, he would make that person familiar with his rapier.

Talking of puberty, Louis – being a bit older than Philippe – had already gathered first impressions and skills in the department of bed-sports by that time. Philippe had not. At least, not with women. He did, however, have a bit of a boyish crush going on in 1658. The lady in question was Henriette de Gordon-Huntley and according to La Grand Mademoiselle, Philippe spent quite some time taking care of Henriette de Gordon-Huntley’s outfits… but that was pretty much it. The lady remained in his good graces all her life and served in the household of both his wives. (There is no document that hints Philippe had sexual contact with any female who was not his wife. I actually checked on this with some people who recently had access to the archives regarding him, and so far nobody has uncovered anything. There is talk of boyish crushes, one on the girl he slapped and another on a Duchesse, but no evidence that those were more than crushes.)

1658 was a bit of a special year for Philippe, in which he was suddenly the centre of attention and nearly became King of France. In May that year, Louis and Cardinal Mazarin went to Dunkirk to inspect the troops. Mama Anne was not really fond of it, but Louis insisted. While Mazarin says Philippe had been invited to join his brother, Philippe’s governor says the opposite. Philippe remained in Calais with Anne and enjoyed the company of the ladies. Louis enjoyed himself a little less. His camp was muddy, with ponds of foul-smelling water and the stench of decaying corpses in the air. On the last day of June, a headache made him retire and a high fever swiftly followed. Only a couple of days later, Louis was in such bad condition it was not sure if he would make it. The physicians tried their very best, consisting of the usual treatments they knew. For them fever meant something was wrong with the blood, thus Louis was bled often. He received enemas, was fed herbal teas and miracle waters, prayers were said and Masses held. Of course, it did not help. Louis was brought to Calais and prepared for his possible demise with confession and communion. Even a special regiment of soldiers was ordered from Paris to Calais in order to return the death body of Louis to Paris. Anne spent her days in tears at Louis bedside, saying she will retire to Val-de-Grace if he should die. Mazarin tried his best to stay calm. It was not just Louis’ condition that alarmed him, but also that the former participants of the Fronde seemed to not be entirely sad about it. The plotting had already started and consisted of plans involving Mazarin’s arrest and the exclusion of Anne from everything if Louis should die and Philippe become King. And for a long two weeks, it looked like this would be the case. A group of people formed around Philippe and flattered him in everything, in hopes that if he should become King, they might get a piece of the royal cake. Letters were exchanged and the future Roi Philippe toasted…. but what about him? It is hard to say what he thought about the whole plotting. What is quite clear, due to various accounts, is his thoughts on his brother’s illness. Philippe refused to leave his brother’s bedside, even after he was urged to do so.

Louis at last recovered and thanks to Philippe’s behaviour, Louis and Anne could be sure that Philippe had no longing to take his brother’s crown. Mazarin thought so too, at least for a while, but had suspicions Philippe might have been favourable to the idea of having him arrested. After Louis returned to health, life went on as usual for Philippe. He amused himself in company of the females and ogled the males. The Comte de Guiche, who had participated in the plotting, was his closest friend… perhaps a little too close for some.

Countless historians have ruffled their hair over what made Philippe prefer men over women. Some say he was brought up effeminate for the very reason that a feminine prince and brother to the King is less danger to said King. If the brother is busy with looking at fabrics, ribbons, shoes and bling, the brother hardly has time to plot to take the crown. Hints on that theory can be found in the writings of the Abbé de Choisy, who played dress up with Philippe, and in those of Philippe’s cousin La Grande Mademoiselle. Both point the finger at Mazarin and Anne encouraging Philippe’s idleness, while neglecting his education, and supporting his fondness of ‘female activities’ like gossiping, dressing up and such things.

Although Philippe had the above mentioned crushes on females during his teens, he also ogled the boys just the same. Especially the handsome Comte de Guiche. Mazarin and Anne apparently did not like this at all and urged the Comte’s father to keep his son away from Philippe. Anne also forbade Guiche to see Philippe when no others were present, which speaks a little against the theory of encouraging the Italian Vice. According to Choisy, he helped Philippe to see Guiche in secret as “one would have done with a mistress“. Henri de Brienne mentions in his writings that Philippe made advances towards him as a teen, but he declined them. Letters by Philippe to the Duc de Candale hint there was a bit of ogling, and perhaps even touching, going on between them as well.

Philippe’s first encounter with a naked male body that was not his own seems to have been with Philippe-Jules Mancini, nephew of Cardinal Mazarin who apparently arranged for the whole thing. Towards the end of 1658, it was quite clear to the court that Philippe’s interest in females did not extend past chattering and while he might find them pretty and lovely, in bed he preferred his own gender. Half a year after his brother’s illness, Philippe showed up at a masked ball in female attire. At that time, Philippe was madly in love with the rather handsome and just-as-arrogant Guiche, who was present as well and pretended, like everyone else, not to recognise Philippe, although they in fact knew it was him. The two went to dance and Guiche thought it funny to shove Philippe about, to twist, turn and even kick his behind. La Grande Mademoiselle observed it all and was shocked, but Philippe, she said, did not mind it. He was so in love, everything Guiche did was fine to him. Anne swiftly heard about the whole thing and scolded her son, but Philippe was not really bothered by it. Instead, he pondered why his mother did not like the Comte de Guiche. (If you ask me, Philippe was the way he was, and people pay way too much attention trying to ‘categorise’ his sexuality. Sexuality is not what defines a person and there is so much more to him that him liking pretty boys.)

Also in 1658, Petit Monsieur was gifted a rather special treasure by Mazarin. In October, Philippe and Louis payed a visit to Saint-Cloud for an entertainment and Philippe fell immediately in love with the property overlooking the Seine. It was thus bought for him for the sum of 240 000 livres.

In 1660, Petit Monsieur became Monsieur. His uncle and friend, Gaston de France, died on February 2 that year and large parts of Gaston’s possessions reverted to the Crown due to his lack of direct male heir. Philippe, as his nephew, was the one next in line for the title Duc d’Orléans, plus the appanage that came with it. For Philippe, it meant a certain degree of financial freedom and independence. For Mazarin and Louis, this was a bit of a problem. While the title was swiftly granted to Philippe and he began to style himself as Duc d’Orléans, the money was a different matter. Until this point, Philippe lived and paid his Household from the means granted to him by his brother. But now, this new appanage meant Philippe was not entirely dependable on the good graces of his brother anymore in matters of money, but would have his own income – an income Louis could not touch – for the rest of his life. Along with the appanage, Philippe could also lay claim to the governorship of Languedoc, which was a bit of a problem too. With his own province, Philippe was even more independent, and while as governor he still had to follow what his brother said regarding it, this meant more money for Philippe and at least the very theoretical chance he might use his province against his brother, as others had done during the Fronde. Louis’ greatest nightmare, although Philippe never showed any interest in becoming king himself. It is no surprise that in the end, Philippe – who firmly believed he would get the governorship – did not get it. As for the appanage, it was granted to him… upon his marriage.

The prospect of marriage did not shock the new Duc d’Orléans. He had already brought the topic up before an appanage was in sight, but Anne and Mazarin had to get Louis married first. Philippe understood perfectly well that his preference for boys did not play any role in the matter. He knew that his marriage was political and he had a duty to perform. As Louis’ wedding was sorted, Mazarin shifted his attention to Philippe and a possible bride. Said bride was not hard to find and lived in France already. She was his cousin, the daughter of Charles I and sister of Charles II. Minette, as her brother called her, came to France as an infant and was more familiar with France than England. For a while she dreamed of becoming Queen of France, but Louis had not much interest in her. In fact, she was not of much interest to anyone until her brother claimed the throne of England: before that, she was the daughter of a beheaded king and sister to a king without a kingdom. The Philippe-Minette match served Louis as well, for if his brother was married to Minette, it would bind the interests of France and England, plus give French support to Charles. Minette agreed and so did Philippe, being in a haste to get the whole thing done. On March 31 in 1661, Philippe de France and Henrietta of England married in the Palais-Royal in presence of their families. (For more on the wedding itself, click here.)

Philippe was now in possession of his own home, had independent financial means, a household and a wife who enchanted everyone. Minette became the jewel of the court, praised for her beauty, wit, charms, everything one can imagine, although her face was a bit too long, her figure not really considered sexy and she also had a bit of a hunchback. Philippe found himself equally enchanted and used every chance he could get to show his wife off. He made sure she wore the most fashionable gowns, had enough jewels at her disposal and did not lack a thing. Monsieur’s Madame became the highlight of every social gathering and he was quite proud of it.

However, this newly wedded joy did not last long. The couple was invited by Louis to join him in Fontainebleau and off they went. Philippe must have been aware that his wife’s charms also attracted others. He saw the gents glance at her and he also heard how Minette charmed Admiral Montague and the Duke of Buckingham during her trip to England to visit her family prior to the wedding. Minette returned with the charmed Buckingham, which already made Philippe a little jealous. Mama Anne assured him that it was not Minette’s doing, and the Duke was returned to England. One can argue that it might have indeed been Minette’s doing, for until this point, she had lived under the care of her mother, who did not allow her too much fun, and now as Madame, she was free from the reproaches of her mother and curious to see how far she could go. After all, people found her rather pretty and she was in possession of youthful charms. She turned the heads of every male being with ease… including that of Louis XIV.

Before Minette became the wife of his brother, Louis had no interest in her. He even joked about her figure in the company of Philippe shortly before the wedding. Some years earlier Louis had refused to dance with her, which brought him a mighty fine scolding from Maman. Minette was still not really his type, but she was fun and his own wife heavily pregnant. Thus Louis amused himself in the company of his sister-in-law: they bathed in the river, had long strolls and talked about whatever came into their minds. Nobody, apart from them, can say how far they went… but it was enough to cause talk of an affair. Philippe tried to reason with Minette but in vain, transporting him into a stage of furious jealousy. For him, the whole thing was one big punch in the face. The brother, who always got more attention, even from their mother, the brother who had everything while he was only allowed a little, might now also claim the one thing he was supposed to have for himself, in which said brother had no interest previously. His wife. (At this time, a wife was a husband’s possession, and while nothing much was said if the husband had a mistress – something which was expected – the wife, on the other hand, was supposed to be the image of virtue, an image that also reflected on her husband. If the wife was cheating, it was way more of an issue, because it implied the husband did not have the power to ‘control’ her. And if he could not do this, it meant he was no man and held no authority in his own household.)

Philippe felt utterly humiliated. He thus turned to Anne and teamed up with his aunt and Minette’s mother, which led to a bit of serious talking with Louis and Minette. Whatever went on, Minette did not want to give it up and decided to arrange for a distraction. Mademoiselle de La Valliére, one of her ladies and plain enough to not steal the show, was chosen to be that distraction. Louis was to ogle and court her during his visits to Minette so that the court would think he had no interest in Minette. Louis agreed and did as he was told… then something happened that neither he or Minette had expected. He actually fell in love with the decoy.

Now Madame was the furious one. She tried her best to get Louis’ attention back but failed. But lucky for her there were plenty of others to flirt with and again, Philippe was humiliated by it. Minette’s attention turned from the King to Philippe’s favourite, the Comte de Guiche. Guiche had done a far bit of Minette ogling already, but Minette did not care too much for him. Philippe was a little annoyed by it – after all, Guiche was his good friend, and he had urged his wife to be a little more friendly to him. You can guess what happened and Philippe had no clue about it for quite a while. But when he did find out his wife was now a bit too friendly with his own lover, he completely lost it. (Can’t blame him.)

Monsieur broke with Guiche, or Guiche with him, in a manner that caused another scandal due to Guiche acting as if he was equal in rank to Philippe. The Duc d’Orléans was the laughing-stock of the court. First, his wife cheated on him with his own brother (or so everyone thought) and then with his own lover. Things could hardly get more embarrassing for Philippe. It had not even been four months since the wedding, and his marriage had become a farce. Philippe could not even be entirely sure if the child his wife was carrying was his own. There was plenty of talk of how the father could be found on the throne… and if this was indeed the case, how could his brother do this to him? Bad enough that everyone was talking of the flirting, which made Philippe look like a fool, but flirting takes two and Louis had displayed a lot of gallantry towards Minette… what if this gallantry had extended to the bedroom? There was no way he could know if this was true or not. On top of that, Philippe’s own bedroom activities with his wife were not really successful at first. During the wedding night no performance could take place, because the bride was visited by Monsieur le Cardinal, a 17th century phrase for menstruation, and afterwards, as Monsieur le Cardinal had disappeared, Philippe found himself, for reasons unknown, unable to entertain the bride to her satisfaction.

At least the issue with Guiche got somewhat solved. When the father of the Comte de Guiche heard how his son acted towards a Prince of France, he was rather shocked and ordered his son to leave court at once. Philippe might have felt a little relieved by that, as he could not escape marriage and his wife, but at least he had one less problem as the couple returned to Paris in order to set up their households. Louis XIV had kindly granted Philippe use of the Palais-Royal as his Parisian residence and now staff had to be found, positions filled and reparations had to be carried out. Monsieur dived into issues of staff, appointments, decorations, planned amusements, and did all of it with a new friend by his side. They had known each other since childhood and most likely played together as well, their parents had been on very friendly terms and so were their brothers. A set of two Louis and two Philippes.

There are various accounts on when and how Philippe de Lorraine, called the Chevalier de Lorraine, entered Monsieur’s good graces, ranging from the late 1650’s to the early 1660’s. He was Prince of the Ducal House of Lorraine with not much money at his disposal, but very fine looking, charming and intelligent. What led this Philippe to get friendly with the other Philippe is unclear as well, however, their attachment would last a lifetime. In him, Philippe found a friend of a very high rank, which in turn meant there was less gossip about it (Interestingly, the greatest issue people had regarding Philippe’s affair with Guiche was not the man-loving, but that Guiche was a mere noble who dared to act like he was Philippe’s equal). With the Chevalier de Lorraine it was different, due to his princely rank, and considered an honour for him to be friends with a Prince of France just like it was an honour for Monsieur to have a foreign Prince as a friend. And with the Chevalier at his side, Monsieur was now in a position to strike back.

Philippe’s relationship with his wife did not improve again, there were merely less and stormy times. Their first child, a daughter, was born on March 26 in 1662. Minette seems not to have been too pleased about the gender: “A girl? Throw her into the Seine.” (One may argue it was said in an emotional state). Marie Louise d’Orléans was born at the Palais-Royal, styled Mademoiselle d’Orleans, and would eventually become Queen of Spain, looking just like her farther in a gown.

Despite the constant tension between husband and wife, or maybe because of it, Monsieur and Madame hosted lavish parties in the early 1660’s. Shortly after Marie Louise’s birth, Philippe had a chance to show off his riding skills in the celebrations of birth of his brother’s heir, aka the Grand Carrousel. Fetes in Paris and Saint-Cloud followed, accompanied by visits to the theatre, masques, carnival and lotteries, which were only briefly disturbed by periods of court mourning and war. While Louis was not too fond of Paris due to the events of the Fronde, Philippe loved the city and the city loved him. Minette carried on with her Guiche affair after he had returned to court, and the whole thing only came to an end in 1665 when Louis XIV got fed up with it.

A miscarriage in 1663 did not really change the routine, but the following year, the birth of a son gave new reason for celebrations. Philippe Charles d’Orléans was born on July 16 in 1664 and given the title Duc de Valois. The birth of an heir did help to smooth the relationship of the parents a little. Philippe was still rather jealous and Minette had not ceased her flirting, continuing to collect admirers. Unfortunately, the little Duc de Valois lived only two years and died in 1666, another special year for Philippe. In January 1666, Philippe and Louis lost their mother to breast cancer. While Louis mourned in private, Philippe was unable to do so. Having always been the one to display more emotion compared to his brother, the death of their mother turned Philippe into a wreck. He locked himself in his rooms. Anne’s death was not a quick one and Philippe, whom she sometimes called her little daughter during his childhood, hardly ever left her side, even saving her from a bad fall by jumping in her path to soften the impact with his own body. Anne gave both sons her blessing before she died and plenty of tears were shed. Louis could not take it: he was close to fainting and left, ordering Philippe to come with him. But Philippe refused and stayed until the end, sending his brother a message that he could not obey him in this matter, but it would be the only time he disobeyed him.

And so, after the death of Anne, the question arose, brought to their attention by Minette: should she, now the Second Woman of France, be allowed to sit more comfortably on an arm-chair in presence of the Queen? Philippe agreed with Louis on the matter – no. Minette should not be allowed to do so, as this was something only queens were entitled to do. And Minette was not a queen.

The death of their mother changed many things for both brothers. For Louis it meant there was nobody left to scold him for showing off his mistresses. For Philippe it meant the loss of an ally, especially regarding the behaviour of his wife…. and everyone would soon see the effects of this. The Palais-Royal had turned into a sort of battlefield, with the troops of Madame and Monsieur at opposite ends and both trying to make each others’ lives as hard as possible. Anne and Philippe had grown close in those last years and Anne clearly sided with her son, even saying that she somewhat regretted helping to arrange the match and that, if Philippe had married his cousin La Grande Mademoiselle instead, things would have been much better. (Louis was against such a match, because La Grande Mademoiselle was the richest woman in France and Philippe would thus have had too much money, too much to depend on the Crown.)

The death of Anne improved the relationship between Louis and Philippe for a while, which had been damaged not only from the Minette flirting, but another matter. As Louis fell ill with measles in 1663, he appointed their cousin Conti as Regent – not Philippe – if he should die. Philippe found a new ally in his confessor, but not for long. When cousin Conti died in 1666, the question of Philippe and Languedoc (which had been given to Conti instead of Philippe after Gaston’s demise) arose again. Now Conti was dead and Languedoc was in need of a new governor. Philippe brought the issue to his royal brother and Louis denied him the honour again. Not quite sure what to do about the new rebuff, Philippe left for his country estate Villers-Coterêts, taking his wife with him. In the meantime, much to her great shock, Madame had discovered that a pamphlet was circulating in Holland regarding her Guiche affair. Terrified it might reach the court of France, she turned to her husband’s confessor, Daniel Cosnac, who saved the day by sending someone to Holland to buy every exemplar.

The following year started a bit better for Philippe. France entered into the War of Devolution and Monsieur had a chance to show his military skills. He did not know too much yet, but was willing to learn so he may serve his brother…. and to gain a little glory for himself. Still new to it all, Philippe had an observer role, following his brother to various sieges and decorating his own tent when he got too bored with observing. Then in July, Monsieur had to leave camp in a hurry when news arrived of Madame being unwell, with another miscarriage the cause. It was her third – the first was in 1663, the second in 1665.

Philippe returned to his brother’s side in August, but by September both were back in Paris. The war was a success and Louis able to show off his military skills for the first time. Philippe did not win any glory, but did win a new lover. His previously friendly relationship with the Chevalier de Lorraine had advanced to something a bit more physical. Lorraine was wounded during one of the battles and Philippe had nursed him back to health in his own fabulously decorated tent. After that, the two Philippes were inseparable and around the same time, the Chevalier’s brother had a bit of a flirtation going on with Madame. He was not the only one.

What went on in Madame and Monsieur’s household during this time could be inspiration for today’s soap operas. Admirers were hidden behind screens, so they could not be seen by Monsieur, who had decided to say bonjour to his wife. Others were dressed as women in order to come and go undetected. Secret messages were exchanged. The whole thing even went so far as to include simple things, like if one preferred Racine over Moliére, with Madame on the side of Racine and Monsieur for Moliére. With all this going on, Monsieur was not entirely innocent in the flirting department, either. After the Comte de Guiche, there was the Marquis de Vardes, who was also the lover of Olympe Mancini and landed in exile for making a rather indecent remark in the presence of the Chevalier de Lorraine. The latter was busy ogling one of Minette’s ladies, to which Vardes said something along the lines of ‘why waste energy on the maid, if the mistress is quite easily to conquer.’ Madame heard of it and Vardes spent some time in the not-so-cosy Bastille. And so, as the Chevalier de Lorraine moved into the position of favourite, Monsieur’s flirting lessened for a while. He fell head over heels.

Oddly, neither Minette nor Monsieur’s confessor did mind the Chevalier at first, but soon he became their worst nightmare. Minette was of the opinion the Chevalier may turn out to be a good friend for her husband, Cosnac thought this Chevalier to be better suited as favourite compared to Guiche, yet was a little worried about the Chevalier’s ambitions. Cosnac, in his role as adviser, pointed out that Philippe should perhaps not have one single favourite, but spread his affections out. Philippe did not care much about this advice and a few days after he left camp during the war in 1668, it was clear he was a bit in love. He awaited the arrival of his Chevalier like a little boy who couldn’t wait for Christmas Day to come. Both walked hand in hand through the gardens and shortly after, during a masked ball, Philippe, dressed in a fabulous low-cut gown, was led in by the Chevalier de Lorraine.

Oddly, neither Minette nor Monsieur’s confessor did mind the Chevalier at first, but soon he became their worst nightmare. Minette was of the opinion the Chevalier may turn out to be a good friend for her husband, Cosnac thought this Chevalier to be better suited as favourite compared to Guiche, yet was a little worried about the Chevalier’s ambitions. Cosnac, in his role as adviser, pointed out that Philippe should perhaps not have one single favourite, but spread his affections out. Philippe did not care much about this advice and a few days after he left camp during the war in 1668, it was clear he was a bit in love. He awaited the arrival of his Chevalier like a little boy who couldn’t wait for Christmas Day to come. Both walked hand in hand through the gardens and shortly after, during a masked ball, Philippe, dressed in a fabulous low-cut gown, was led in by the Chevalier de Lorraine.

With the arrival of the Chevalier, things changed for Madame. According to Cosnac, Lorraine was not really bothered about making friends with her, nor with Cosnac himself. Philippe, encouraged by the Chevalier, took in mind to put an end to his wife’s infidelity. The Palais returned to battlefield mode, with both parties gathering their forces. Now, for the first time, Philippe actually had the upper hand. Lorraine was installed in the best and most comfortable rooms of the Palais-Royal. Slowly but surely, he took control of matters regarding Philippe’s household, which also included Madame’s, and made himself indispensable. Monsieur’s old governor, to whom he owed his position at court, joined along with the most important members of the household. Not a surprise. One word from Philippe would see them lose their positions, and with the Chevalier whispering to Philippe it was very likely. Madame, on the other hand, just had one good card in her deck, Daniel de Cosnac. And he was the first victim of the battle.

Cosnac had lost a bit of favour due to speaking out against the Chevalier taking over everything, including the ladies in Minette’s household. And Philippe was already a bit annoyed with him, since Cosnac had failed to sweet talk the King on Philippe’s behalf regarding the matter of Languedoc. Philippe was also unamused that Cosnac had jumped to rescue Madame’s reputation prior. In the end, the Chevalier got annoyed too, and had little difficulty finishing Cosnac off. He showed Philippe some letters, written in Cosnac’s hand, which stated the confessor planned to get between them. Whether Cosnac had actually written them and where the Chevalier got them from is not known. If they were fake, Philippe might have even been aware of it. Either way, they came in handy and Cosnac was told to leave court.

A wife was not allowed to travel anywhere without her husband’s agreement, while at the same time a wife had to follow her husband wherever he went. That proved to be a bit of an issue for Minette. As Cosnac was forced to leave, he took with him three letters. Letters of an indecent nature and apparently written by the Chevalier to a silly young girl. Madame had planned to show those letters (which might have been fakes too for all we know) to her husband in hopes they might provoke an argument between the two men. She had to get possession of those letters somehow, but Coscac was not allowed to show himself in Paris and Philippe, still eager to put an end to the flirting, did not allow her to go anywhere without him. He was still suffering from a blow the previous year, in 1668. During a fete in summer, Moliére amused everyone with a new play at Versailles. At that time, Madame was followed everywhere by the Duke of Monmouth, a rather handsome fellow, and it was hard to hide from the gossip of Madame’s new affair. Then came Moliére with his new play, featuring a horned-husband. Some thought this husband resembled that of Madame de Montespan, with whom Louis was being merry. Others, including Philippe, saw it as a joke on the King’s brother. The Duke of Monmouth left court the next day.

So, in order to get her hands on said indecent letters, Minette came up with a plan to meet Cosnac at Saint-Denis. She wanted to go there to pray for her mother, who had recently passed away, and Philippe could hardly deny her such a request. It was planned for a disguised Cosnac to sneak inside and hand the letters over, but Philippe got wind of it and had Cosnac arrested before the meeting could take place. How did he hear of it? The Chevalier had planted spies in Madame’s staff and most of her ladies were on rather friendly terms with him. What about the letters? Cosnac apparently managed to hide them before he was arrested. (From all I know, they never showed up again.) As Cosnac was arrested, a piece of paper was found on his person that stated the involvement of Madame de Saint-Chaumont, friend to Madame and governess of her children, in the planned meeting. The lady was thus dismissed and Monsieur’s troops won the first battle of the war. A war that did not go unnoticed by their daughter Marie-Louise.

In 1669, Philippe became father of a second daughter, Anne-Marie, on August 27. Things calmed a little again, at least on the surface. Philippe was unaware of all the letters his wife sent to England, to tell her brother of what was going on. He was busy with amusing himself and showing his Chevalier off. In the meantime, his brother-in-law Charles II formed the opinion that Philippe was a bit of a good-for-nothing, a bit of a pervert who chased after young boys, and whose greatest joy was to treat his poor sister badly. Whoops.

Philippe was still busy with amusing himself when the cards turned in Minette’s favour. The War of Devolution had left Louis XIV with a desire to gather some tulips: he had plans to march into Holland and kick bum, for which he needed the support of the English. As it happened, there was one person at his court in the perfect situation to serve as link between France and England. Minette. After being fairly unimportant to him in the few years, he overcome his heart-eyes for her rather quickly, she was now needed to ensure the English support. Negotiations for a deal between both Kingdoms were already underway as Minette was told of it. The whole thing was meant to stay a secret, so the Dutch would get a hell of a surprise… and that’s what started the next battle between Madame and Monsieur. Charles II insisted his sister must bring the papers to England. Louis XIV agreed. Minette was informed of the most important things in private and the talk started again. Since nobody knew why the King and Madame met in private again, people assumed the worst. So too, did Philippe, and he was furious. He demanded to know what happened, but Louis did not tell him. According to one version of the story, the Chevalier de Lorraine found out what was going on and thus told Philippe, which made him not less furious. Louis then shared the secret, but refused Philippe’s request to carry the papers to England himself or to accompany Minette. Monsieur had no clue how little Charles II thought of him and how he had refused the suggestion. It was all planned out already. Madame and Monsieur were to follow the King to a trip to the coast, where Minette would spy a ship flying the English colours and feel terribly homesick, and in turn Philippe would allow her to visit her English relatives and Louis would give his approval. Minette would board the ship, taking with her the papers for a secret Treaty.

Of course, Monsieur did not like that idea at all and could not understand why he was excluded again. On top of that, he was supposed to play along with their silly plan. He again had no say over anything, not even over his wife. He probably thought it could not get any worse…. but it got way worse. Just like Philippe had no clue of what Charles II thought of him, he had also no clue that Charles suggested, since this Chevalier de Lorraine was so much trouble for his sister, to perhaps have said person removed. On January 29 in 1670, Charles II got a positive reply to his suggestion. The next day, the Chevalier de Lorraine was arrested in the presence of Philippe. (More on the arrest and the Chevalier here.)

As the Chevalier de Lorraine was dragged out and sent en route to a prison in Lyon, Monsieur reacted with a outburst of temper that had been unseen since his teen days. For him, it must have looked like his brother had just randomly taken something from him again for no specific reason. He rushed thus to Louis in order to confront him. The King’s reaction was not what he had hoped for. His royal brother had his reasons, reasons Philippe was not allowed to know, reasons that involved matters he should not know. Philippe’s despair grew and he did the only thing he was able to do in such a situation, to remove himself from court and as far away from Louis as he could. The staff of the Palais-Royal was ordered to pack and Monsieur, dragging his wife along, left Paris, with all his furniture, to Villers-Cotterêtes, where he had once enjoyed private moments in the shadows of the trees with his Chevalier.

By doing this, Philippe caused a proper scandal. A scandal so big, that all of Europe talked about it and while Europe talked, Monsieur turned to Jean-Baptiste Colbert in hopes the Minister might be able to intervene.

By doing this, Philippe caused a proper scandal. A scandal so big, that all of Europe talked about it and while Europe talked, Monsieur turned to Jean-Baptiste Colbert in hopes the Minister might be able to intervene.

“Monsieur Colbert, as for some time I have regarded you as among my friends, and as of them you are the only one having the honour of approaching the King since the frightful misfortune that has just befallen me, I believe you not be angry if I ask you to inform the King that I came here in an extremity of grief that required me either to leave his presence or to remain in his court in shame. I beg him to consider what the world would think of me if it saw me merrily enjoying the pleasures of carnival while an innocent prince and the best friend that I have on earth for the love of me languishes in a wretched prison far away. Furthermore, the manner in which he was seized could not have been more insulting to me, since for some time no one knew if in fact it were I that was to be taken, for my rooms were surrounded with guards at doors and windows, and frightened servants would come to me saying they could not say if it was my person that was wanted. And worse, the King went so far as to ask my wife what she intended to do, thus making it clear that he wanted to authorise her not to follow me, as her duty required. Even so, if I believed I might be useful to the service of the King, I should not have left him, but the manner in which he has treated me all his life make me think just the contrary.”

Letter after letter left Villers-Cotterêtes for Paris. Philippe made it rather clear that he would not return unless the Chevalier was set free. Louis did not want to hear anything about it, yet he needed his brother to return. Only his return could stop the talk of what was really behind the arrest and, more importantly, only his return would bring Minette back to court, so she may go on her special mission. Instead of giving in to his brother, Louis did the opposite and ordered the Chevalier to be brought to one of the worst prisons in France. In turn, this made Philippe only more firm in his demands. Either the Chevalier was set free, or he would stay where he was at Villers-Cotterêtes, so far away from Paris by 17th century standards that it was nearly at the end of the world. He did so for twenty-five days. Only then was an agreement concluded. Monsieur and Madame were to return and the Chevalier released and exiled.

Officially, Monsieur returned out of free will and without any amends having been made, but once again the whole thing was much bigger than it appeared at first glance. Philippe was no fool and knew that Louis needed his wife at court in order to seal the deal with England. He may not have been aware how much England had to do with the arrest, but he knew that England, in order to make the deal, could urge Louis to come to agreeable terms with his brother. Which is what seems to have happened. Monsieur wrote his English brother-in-law, hinting how he would not return, and thus Charles wrote Louis, hinting that something had to be done.

Yet Philippe did not return as a victor to court. He had done what was possible, getting the Chevalier released, but was still without him. He had to face his brother, acting as if nothing happened, and smile at his wife, convinced she was behind it all. His foul mood did not vanish, but increased as Louis attempted to gain his brother’s approval for Minette’s trip. Everyone clearly saw that something was amiss, but what was he supposed to do? He had to give in. And so he did. The court went on a trip and Madame, as planned, to England. (On the way to Flanders with King, Queen, Madame and Monsieur all in one carriage, the mood was so low that Philippe remarked, as he saw his wife was not feeling well, how he was once told he would have more than one wife and by the look of her, it would not surprise him at all.)

Monsieur’s mood did not brighten during Madame’s voyage and when the time came to welcome her back in France, he refused to do so. For him, she was the reason for all his troubles these last years. Etiquette required him to meet and escort her back home, but was so hurt he could not. Not just over the arrest of his friend, but also because his wife was allowed to do something he would never be allowed to do himself – mingle in politics. Louis made it clear he did not care what his brother thought of it and although he had promised Philippe he would only advance a little towards Madame, he was now embracing her and showering her with praise. So, Madame became the jewel of the court again upon her return. Louis honoured her with attention, the court listened to her stories and admired the presents she had received, and she bathed in her own self-importance. Her husband watched it all in silence, suffering quietly, knowing the true reason behind the trip, but not allowed to spill the beans. But what he could do was remove her from the centre of attention. The King intended to relocate himself to Versailles and so Philippe ordered Madame – who would have loved to bathe in the Sun a little longer – follow him to Saint-Cloud. A couple of days later, she died.

Minette had not been in good health as she left for England. It seemed her health improved a little during the visit, but on the way back it plumeted again. She was not able to eat, only drank milk, was not able to sleep, to sit still, to rest. One afternoon, her face swelled up so much it was hard to recognise her. Plus, the pain in her sides, of which she had suffered for years already, gave her a hard time. Madame passed away in Saint-Cloud, aged only twenty-six, on the last day of June in 1670. (More on the death of Madame here.)

Although Philippe and Minette were far from in love with each other and he might have even wished to be free of her in the past, her sudden death came as a shock to him. Since it was so sudden and due to their tension, rumours immediately started that Philippe might have something to do with it… and were swiftly dismissed again. He was way too affected and his tears honest, they thought. Thus the participation in a plot to murder Madame was not thought possible, at least by Monsieur. Talk shifted to how Monsieur’s friends murdered Madame. Apparently the Marquis d’Effiat had received a gift of a poisonous nature from Rome, where a certain Chevalier de Lorraine was making merry with Marie and Hortense Mancini, people said. The Marquis then spread the poison all over Madame’s cup and she came into contact with it as she had her usual glass of cold water. While Monsieur’s participation was dismissed quickly, the participation of the rest seemed likely to the court. Charles II, however, could not entirely dismiss his brother-in-law in his precious sister’s death.

Now a widower, the Duc d’Orléans left Saint-Cloud for his Parisian residence, the Palais-Royal, and busied himself with his dead wife’s funeral as befitted her rank. As he did so, he was most likely aware he would not stay a widower for long. Philippe was still young and lacking an heir. The expansion politics of his brother were not seen with pleasure by many states: as he had bound France to England, he would now establish a link to another European ruler by marriage. Or Philippe would marry his cousin Anne-Marie Louise d’Orléans aka La Grande Mademoiselle. The lady in question apparently was rather worried about this – years ago she was not really against it, but now she was madly in love with someone else. Louis XIV had apparently suggested such a match shortly after Minette’s demise, shocking La Grande Mademoiselle. The topic was again brought up only a bit later, with Louis telling her Philippe was not entirely appalled by the idea. La Grande Mademoiselle was thirty years his senior, but had a lot of money and property. She was his friend, one of a few he had from his childhood, and thanks to her father, she knew what it meant to be brother to a King. Philippe planned it all out and even hoped, likely due to the age difference, that no children would be produced, in which case, la Grande Mademoiselle would leave her fortune to his oldest daughter, who in turn would marry the Dauphin and make him father of the Queen of France. Of course, this strange plan had no chance to be accepted by King and the lady in question, so was dismissed.

In the end, the new wife-to-be was a German princess with relations to the House of Stuart and whose father could prove himself a good ally to Louis XIV in his struggles with the Dutch. She had just turned eighteen and was in good health, with a bit more of a robust figure and promising hips. She was no beauty and her family not really rich, but Philippe did not mind. He was far from being in love and although he had other male lovers, he still mourned the absence of his Chevalier.

Marriage was business and like his first, this second one would be too. At least he could celebrate this one in style and the fact that it took a year for everything to be settled gave him plenty of time to arrange celebrations. He travelled to meet his new bride half-way and was not really impressed by her looks and her habit of saying what she thought. What did not impress him either was how this Élisabeth-Charlotte did not think much of fashion. Luckily, he understood the importance of fashion well and thus took to dolling her up. (For more details on the wedding, click here.)

In contrast to the first marriage, the second one would be a bit more of a success. For a start, the bride was not at all interested in flirting and such things. The first few years were quite happy ones, and the only thing that irked Philippe was, once again, his brother. Louis had developed a fondness for the new Madame. Not the same kind of fondness he had for the first Madame: this one was more based on the love for nature. Élisabeth-Charlotte, aka Liselotte, loved to go hunting. Her hubby did not. He did not enjoy riding in the sun, where he might get a tan and his outfit might get stained. Insects, mud, wind that ruins one’s hairdo, and all that. Thus Louis took to taking Liselotte on the hunt. And while Liselotte said she could not wish for a better husband, she felt quite the admiration for Louis.

Then finally, an heir was born. Liselotte gave birth to a healthy boy around eighteen months after their wedding: Alexandre-Louis was born on June 2 in 1673 at the château de Saint-Cloud. The proud papa rejoiced, but unfortunately Alexandre-Louis died not yet aged three, most likely due to bloodletting. As Alexandre died, Liselotte was already pregnant for the third time. On August 2 in 1674, she gave birth to another boy, named after his papa, who would become Regent of France one day. Half a year after Alexandre’s demise, she gave birth to a daughter, Élisabeth-Charlotte, on September 13 in 1676, who would eventually become the grandmother of Marie-Antoinette. After the birth of their third child, Philippe suggested the couple should sleep in separate beds and Liselotte was quite happy about that, as sleeping in a bed with Philippe was not too pleasant. He scolded her often, when, while asleep, a part of her body accidentally touched his (Liselotte writes that he made her sleep at the very edge of the bed). An anecdote from the time when Philippe had nearly become King reports how Madame de Monaco made advances and dared to touch him, which he later described in such terms as if he had nearly been raped. It seems Monsieur was generally not fond of being touched by the female gender, nor was he himself fond of touching them either. He was once teased and encouraged to touch a lady he was familiar with but could not do so without putting gloves on first.

During these years, Monsieur seems to have been quite happy, at least happier than his first marriage. The second one went well and finally after a long absence and exile, his Chevalier was allowed to return to France. While Louis made the whole thing look like an act of brotherly affection, there was again more behind it. During the Chevalier’s absence, Monsieur’s many admirers had become a bit too demanding. Philippe came to his brother all the time to demand this or that for one of his friends. He had done it for the Chevalier as well in the past, but not that often. Allowing the Chevalier to return, Louis could be sure, meant the Chevalier would take the reins back. He would control his brother’s household again and control his brother as well. Order would return. Philippe would stop pestering him for favours for the various men who shared his bed. On top of that, the Chevalier was a great warrior and Louis needed all skilled soldiers he could find, because he was preparing to go to war again. Thus the King made a deal with the Chevalier, in which the latter was allowed to return if he promised to talk sense into Philippe – ergo, if Philippe did not agree with Louis on a matter that needed Philippe’s agreement, the Chevalier was to sweet-talk him and make him agree.

A new war also meant that Philippe would finally have a chance to show his warring skills. Philippe was not at all a coward when it came to this. Although he paid great attention to his attire and the decoration of his campaign tent, he did not hide himself away. When he was seven, he had accompanied his brother to a siege and his governor noted to his great satisfaction how Philippe did not appear to be scared at all. During the War of Devolution, Philippe often visited the trenches, bullets flying over his head. As Monsieur was given a command during the Dutch War, he surprised everyone. He was made second-in-command to Louis and participated in many sieges and carried out independent missions. In 1677, he even beat the great enemy himself, William of Orange. This battle went into the history books as Monsieur’s greatest victory – and ironically, his last one.

In March 1677, Monsieur joined his brother at the siege of Valenciennes. Three days later, after the city was taken, Louis moved towards Cambray, while Philippe was sent to lay siege to Saint-Omer. Everything went according to plan and the camps were set up, when Louis received news that a certain William of Orange, who had given him so many nightmares, might be heading towards Philippe’s location to help the besieged. At first, there was not much reason to worry, because it seemed these troops were few and ill-equipped. So Louis sent his brother more infantry and cavalry to aid him, in the hopes that when the French outnumbered the Dutch, the Dutch might refrain from an attack. Philippe’s Maréchal du Camp was advised to avoid getting into a fight with William of Orange, for it might end with a defeat… like the defeat Louis had to suffer already. Philippe was supposed to carry on with the siege, but he saw it a little different. With the new troops his brother sent him, he thought he might actually be able to kick some Dutch bum. And that is what he did.

In March 1677, Monsieur joined his brother at the siege of Valenciennes. Three days later, after the city was taken, Louis moved towards Cambray, while Philippe was sent to lay siege to Saint-Omer. Everything went according to plan and the camps were set up, when Louis received news that a certain William of Orange, who had given him so many nightmares, might be heading towards Philippe’s location to help the besieged. At first, there was not much reason to worry, because it seemed these troops were few and ill-equipped. So Louis sent his brother more infantry and cavalry to aid him, in the hopes that when the French outnumbered the Dutch, the Dutch might refrain from an attack. Philippe’s Maréchal du Camp was advised to avoid getting into a fight with William of Orange, for it might end with a defeat… like the defeat Louis had to suffer already. Philippe was supposed to carry on with the siege, but he saw it a little different. With the new troops his brother sent him, he thought he might actually be able to kick some Dutch bum. And that is what he did.

Monsieur moved his troops into a position that made it impossible for William of Orange to reach Saint-Omer without first engaging in a fight. Contrary to the talk of Philippe still being in his tent and arranging his hairdo as William came into sight, Philippe was actually all set at dawn, awaiting the arrival of the enemy. At his side, the Chevalier de Lorraine and Marquis d’Effiat. Philippe led the charge, with Luxembourg controlling the left wing, Humiéres the right. The Dutch approached and attacked the very left of the French line, in hopes to break through quickly. For that, William moved more troops to his right and exposed his left. Monsieur saw it and swiftly ordered Humiéres to attack William’s left. Success! But now the French centre was in trouble. The troops in the centre got a bit overwhelmed by the force of the attack and Philippe rode out to lead and encourage his troops, into the midst of the fighting. A bullet hit his armour, another killed his horse beneath him. The Chevalier was hit by a bullet and injured at the temple. The French centre broke through and sent the Dutch running. William could not believe his eyes and ordered his troops to return, even attack them and slashed their faces. All in vain. They ran and Philippe was victorious, defeating William of Orange in direct battle. Something his brother never managed.

Philippe at once sent a messenger, the Marquis d’Effiat, to inform his brother of the victory (the Chevalier was too badly wounded to ride, otherwise he would have had the honour). Louis received the news and declared he could not be happier for his brother, yet inwardly his reaction was much different. Philippe had stolen the show and bathed in Louis’ glory. Instead of taking advantage of his brother’s skills, Louis did not give Philippe another command and Philippe had to return to his role of observer.

Without the prospect of winning glory on the battlefield, Monsieur returned to his favourite pastimes – gossip, gambling, collecting and the dolling up of the Palais-Royal and Saint-Cloud. In the case of the Palais, Philippe invested in renovations and decoration in the 1660’s and the 1690’s. (The Palais was not officially Philippe’s until 1692. Before ’92 it belonged to Louis.)

Philippe amassed quite the collection of objets d’art, ranging from paintings (he liked the Dutch painters; Louis disliked them) to vases, centrepieces, porcelain, statues, bowls, all sorts of silver and gold objects, carpets, tapestries and so on. He was less fond of medals. After the death of Liselotte’s father, Philippe had to choose between tapestries or medals. Liselotte, who already had a medal collection, wanted the medals. Philippe said no. The medals would only be of use to her and not him, therefore he would take the tapestries…. which then ended up with the Chevalier de Lorraine. Precious gems formed a large part of the collection, too: Rubies, sapphires, diamonds, emeralds, with an estimated value of 1,623,922 livres, set into rings, bracelets, necklaces, earrings, sword-handles, snuff-boxes, brooches, crosses, and everything else the fashionable man needed.

In 1679, Philippe saw his oldest daughter Marie-Louise become Queen of Spain. The marriage was an attempt to create a better relationship between France and Spain. The groom, however, was not an entirely handsome one. Charles II of Spain, born in 1661, was the result of many generations of inbreeding within the Spanish royal house, and born physically and mentally disabled, disfigured, with a tongue so large he could hardly speak. Plus he did a fair bit of drooling all over the place. Apparently, Marie-Louise, as she was shown a portrait of her future husband for the very first time, was told an unskilled painter was the reason for the ‘ugliness’ of the groom. She did not buy it. From the time of her betrothal in July to the day of her marriage by proxy and her departure, Marie-Louise was in tears – as was her papa. It was clear to both that they would not see each other again because as Queen of Spain, Marie-Louise would not be allowed to leave Spain and Philippe, as brother to the French King, would never be allowed to leave France. It was also clear that Marie-Louise would probably not enjoy herself in Spain, even if the match itself was fabulous. One of Monsieur’s daughters, a Queen…. not of France, but of Spain, at least. He was rather pleased about it and so was Liselotte.

Five years later, in 1684, Monsieur’s second oldest daughter was married. To maintain French influence in Italy, Louis XIV arranged for Anne-Marie to marry Victor-Amédée II de Savoie, Duc de Savoie and later King of Sicily and then Sardinia. The bride was not yet fifteen and the court still in mourning for their own Queen. Marie-Thérèse had died in summer of the previous year, thus the ceremony was less grand that her older sister’s. This marriage saw nine children born to the couple. The oldest, Marie-Adélaïde, married the son of the Dauphin of France and became the mother of Louis XV. As his grand-daughter Marie-Adélaïde arrived in France, aged only 11, and Monsieur saw her for the first time in person, the proud grandpa was so enchanted and overtaken with joy he forgot all etiquette and greeted her before it was his turn to do so. It was probably the only time Philippe ever ignored etiquette (and of course, Louis pointed this out to Philippe). Marie-Adélaïde herself was quite taken by her grandpa too, although she found him a ‘little fat’, and often visited him in Saint-Cloud. Philippe had indeed grown a little belly over the years. He always had been very fond of everything sweet, ate pure marmalade with a silver spoon, had bonbons in his pockets and always a table full with all sorts of delicious things in his apartment.

The next one to be married was Philippe’s heir, the Duc d’Chartres, and this marriage was a proper scandal. “I care not that he love me, but that he marries me” said the bride, who was nicknamed Madame Lucifer by the groom. It was one of Louis XIV’s legitimised daughters with Madame de Montespan and the King was eager to have that one married to his brother’s heir. He offered a dowry of two million livres and the Palais-Royal to the parents of the groom to sweeten the mésalliance… yet it was clear to Louis that the mother would probably never agree. It was a marriage between a bastard, Françoise-Marie de Bourbon, and true royal blood, which would lift the bride in rank and importance. The only real winner would be Louis himself. Chartres would inherit everything from his father and continue his line with a daughter of Louis. The King was aware that Monsieur and Madame would not be too happy about the match, but luckily, he only really needed to persuade Monsieur. If he agreed, the son would agree too, and if father and son agreed, the mother (who was known to have a extreme dislike for bastards) could do nothing about it. Louis apparently sent the Chevalier de Lorraine to talk with Philippe about it and Philippe was promised all sort of things for himself and his son by Louis. He agreed in the end, but would later regret it since none of the promises were really kept. So, after the father then the son agreed, the mother could not do much…. apart from giving her son a good slap in front of all the court. The marriage took place and the wife of the future Regent of France was lifted from the ranks of royal bastard to Royal Highness and Grand-Daughter of France. (The full story of the Chevalier’s involvement can be found here.)