La Maison de la Reine

Louis XIV’s court, and the French court in general, had a lot of court offices for male beings… and not so many for females. The Queen’s of France did not get their own Households until the 12th century and compared to how many people had offices in the Maison du Roi, the King’s Household, the Maison de la Reine was quite small.

For the Queen to have ladies, separated in dames and demoiselles, did not really become a thing in most of Europe until the late 15th century. At that time the court structure changed to a more fun-loving Renaissance style and it was considered to be more representative if the Queen had ladies at her side. Before that, the court was quite a male dominion….but to quote François Ier “A court, without ladies, is a court without a court.”

The highest ranking office within the Maison de la Reine was created in 1619 and called Surintendante de la Maison de la Reine. She was the senior of all the dames and demoiselles within the Queen’s Household and as the name hints, her job was to coordinate everything. She was the one to made sure that everything went according to the Queen’s daily schedule, supervised and was responsible for all the staff of the Queen’s Household… which was not always an easy task, for example, when a certain young and dashing King went after the pretty ladies of his wife’s Household. She also took the oaths of all other ladies of the Maison.

The Surintendante for the Household of Anne d’Autriche was Marie de Rohan, Duchesse de Chevreuse, from 1619 to 1637 and from 1657 to 1666 Anne-Marie Martinozzi, Princesse de Conti. During the time of Marie-Thérèse d’Autriche, this position was held by Anne de Gonzague de Clèves from 1660 to 1661. She was promised the position by Louis XIV after the end of the Fronde, but had to give it up after just a year, not because she did her job badly, but because Louis XIV wanted to give the position to someone else. It was Olympe Mancini, Comtesse de Soissions, and she held it from 1661 to 1679. The Comtesse then had to give the position up, on request of the King, and it was given to Françoise-Athénaïs de Rochechouart de Mortemart, Marquise de Montespan, in an attempt to make her a little less annoying in the eyes of the King. Madame de Montespan held the position from 1679 to 1683, the year the Queen died.

France did not get a new (official) Queen until 1725 and without Queen there was no Maison de la Reine. The office of Surintendante de la Maison de la Reine and that of Gouvernante des enfants royaux, were the two highest ranking offices for females at the court and both required an oath of fealty to the King.

Just below in rank of the Surintendante de la Maison de la Reine, was the Première dame d’honneur. This officeholder was pretty much the deputy of the Surintendante, although the office of Première dame d’honneur is a good 100 years older. Before the office of Surintendante was introduced, the Première dame d’honneur was the head of the Queen’s Household staff. The general term of dame d’honneur, for a married lady-in-waiting, dates back to the same time, 1523, hence the prefix of Première to distinguish this lady and her higher rank within the Household from the other dames d’honneur.

During the reign of Marie-Thérèse d’Autriche the office of Première dame d’honneur was held by Susanne de Baudéan de Neuillant de Parabere, Duchesse de Navailles, from 1660 to 1664. Julie d’Angennes, Duchesse de Montausier, from 1664 to 1671. Anne de Richelieu, Duchesse de Richelieu, from 1671 to 1679; and Anne-Armande de Crequy, Duchesse de Créquy, from 1679 to 1683.

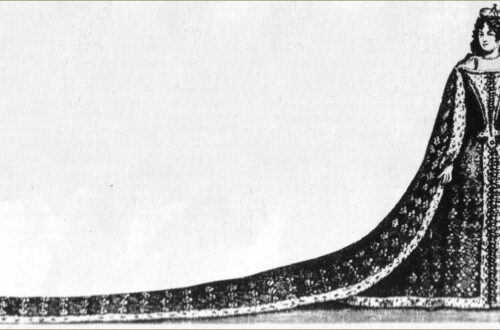

Next in rank was the Dame d’atour. This office was created in 1534 and, like the two office ranking above it, could only be awarded to loyal women of the high-nobility. It was the job of the Dame d’atour to take care of the Queen’s wardrobe as well as all of her jewellery. She was also the one to supervise the Queen’s dressing in the morning and all change of clothes and her undressing in the evenings. In case both the Surintendante de la Maison de la Reine and the Première dame d’honneur, were absent at the same time for whatever reasons, the Dame d’atour acted as their deputy. Another task the Dame d’atour had, was to check the Première femme de Chambre.

Anne d’Autriche had a whole lot of Dames d’atour during her life, 8 of them in fact, while Marie-Thérèse d’Autriche only had one, Anne-Marie de Beauvilliers, Comtesse de Bethune, who held the position from 1660 to 1683.

The dames d’honneur, or short simply dames, are the next in rank. Their among and the office holders were ever-changing, but their general job was to serve as companion to the Queen, to accompany her, to assist her, to hand her a glass, or a handkerchief, to entertain her… and they often stole the show. They sang, they danced in ballets, they were praised in poems. The Queen was generally in company of a few of them wherever she went, thus they had plenty a chance to show off… and impress the King. Quite a few of them eventually got to know the King a little better. Louis XIV also liked to give this position to his married love-interests, so he would only need to visit his wife, which he had to do anyway, to spent some quality time with this or that dame he was after… like in case of Madame de Montespan.

The filles d’honneur or demoiselles d’honneur are next. They rank under the married dames d’honneur and as the name hints, they are unmarried daughters of noblemen… and another of the King’s favourite hunting grounds. They share the duties of the dames d’honneur, but are actually more there to learn all they can about etiquette, court-life and to find a suitable, preferably handsome, husband. To make sure the demoiselles were not taken advantage of, they were watched by the Gouvernante de filles, one of the dames d’honneur who was charged with looking after them and assisted by a sous-gouvernante.

The positions of both the dames and filles/demoiselles was abolished in 1674, as the Maison de la Reine was restructured. A new office, called dames du palais, was created and limited to twelve married ladies who took over the tasks of the dames and filles/demoiselles.

Last, but not least, among the offices is that of the Première femme de Chambre. This office, due to direct access to the Queen was quite sought-after. The Première femme de Chambre oversaw all the femmes de chambre, chamber-maids, and also the lavandières, the ladies who washed the garments of the Queen. It was her job to prepare all the clothes the Queen might wear during the day, select and prepare the cosmetics and everything else that was needed for the dressing in the morning, undressing in the evening, and change of garments during the day. The position of Première femme de Chambre, came with something very special. She had the keys to the Queen’s apartments and this direct access at all time. This put her in the unique position to influence who might get a private audience and who not and also made her the best candidate to forward messages to the Queen. As you might guess, many attempted to flatter and bribe the officeholder.

Last, but not least, among the offices is that of the Première femme de Chambre. This office, due to direct access to the Queen was quite sought-after. The Première femme de Chambre oversaw all the femmes de chambre, chamber-maids, and also the lavandières, the ladies who washed the garments of the Queen. It was her job to prepare all the clothes the Queen might wear during the day, select and prepare the cosmetics and everything else that was needed for the dressing in the morning, undressing in the evening, and change of garments during the day. The position of Première femme de Chambre, came with something very special. She had the keys to the Queen’s apartments and this direct access at all time. This put her in the unique position to influence who might get a private audience and who not and also made her the best candidate to forward messages to the Queen. As you might guess, many attempted to flatter and bribe the officeholder.

In case of Marie-Thérèse d’Autriche, her Première femme de Chambre was her very favourite. As Marie-Thérèse arrived in France, she was accompanied by a whole lot of Spanish ladies. All, apart from one, were sent home over the course of the years. The one to remain at court was Doña Maria Molina, aka La Molina, and she was made Première femme de Chambre. La Molina had a very special place in Marie-Thérèse’s heart and was sort of her best friend and confidante. She also often slept in the Queen’s bedchamber, who suffered of anxiety and nightmares, read her stories, held her hand…. rumour has it, Louis XIV had to coerce her out of the Queen’s bedchamber more than once, when he wished for a private moment with his wife.

A structure similar to that of the Maison de la Reine, was common for the Households of most of the females of the Royal Family and variations of it, with less positions, for the females of the nobility depending on their ranks and status of the family.