The wedding of Marie-Louise d’Orléans and much ado about etiquette…

The highlight of the year 1679 at court was the marriage by proxy of Mademoiselle and the King of Spain. Mademoiselle was the oldest daughter of Louis XIV’s brother Philippe and his first wife, Henriette d’Angleterre. Since none of the Sun King’s legitimate daughters reached adulthood, this was his first chance to marry a close relative to another King. But the whole thing was a bit of a nightmare in matters of etiquette and precedence due to foreign attendance, the question as to when Mademoiselle should be treated as Queen of Spain and on top of it, Louis decided his illegitimate offspring should take formally part as well.

Mademoiselle was not at all happy as she was informed she ought to marry the King of Spain. Charles II was the younger half-brother of Louis XIV’s wife Marie-Thérèse and this marriage was arranged to bring France and Spain closer together again… and also so that Louis might have the chance to control Spain a bit, because Charles II was far from being a strong King like Louis. Poor Charles was seriously handicapped. The infamous Habsburg inbreeding made him physically and mentally disabled. He was of a weak health, it was considered a miracle he reached adulthood at all. His prominent Habsburg chin and lower lip made it hard for him to speak and he drooled quite a bit. He was not handsome either and all in all not the kind of man a beautiful young Princesse would want to marry.

Marie-Louise apparently fainted as she was presented with a portrait of her groom. She begged uncle Louis to spare her from marrying the King of Spain, in vain of course, and spent plenty of time until her marriage in tears.

She was probably not just upset, because the groom was not a Prince Charming. The fact that she would have to leave France, her papa, step-mother and siblings surely played a huge role as well… but that was the fate of most royal Princesses and Mademoiselle had not the means nor the independence just to say non, like la Grande Mademoiselle had done when it was suggested she should marry the way more handsome King of Portugal.

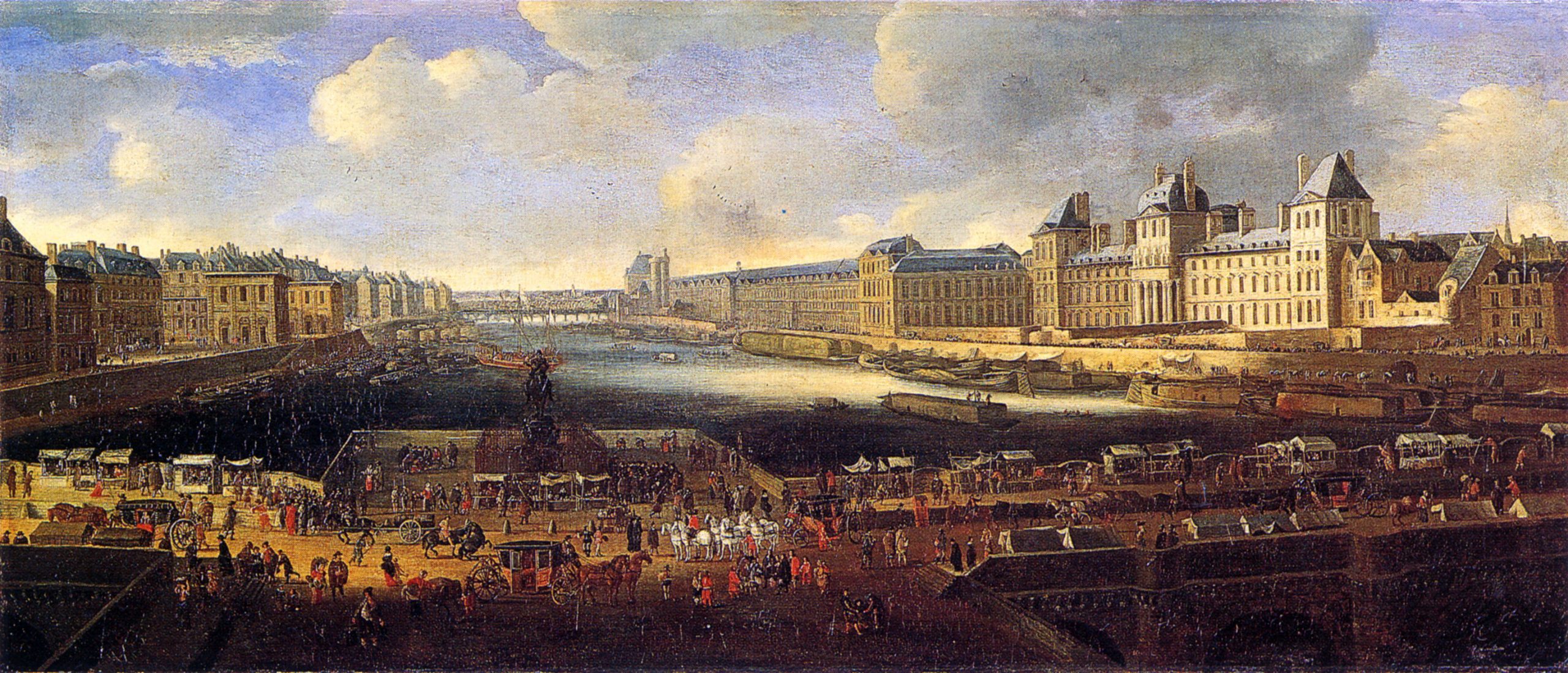

After the negotiations were done, the date for the official engagement ceremony and signing of contracts was set to take place on 30 August 1679 in the King’s cabinet of the Château de Fontainebleau. The wedding par procuration – per proxy- was scheduled to take place the following day, on 31 August 1679, in the Chapelle Saint-Saturnin of the Château.

It was considered a great honour for Mademoiselle to marry a King. Her papa, although very sad to let his daughter go, thought the same and thus involved himself greatly in the preparations. He was incredibly proud to be the father of a Queen and wanted this wedding to be the most splendid wedding the court had ever seen. As always, when there was a huge court event, court robes were mandatory and Mademoiselle, of course, needed a magnificent wedding dress.

And that was the first problem. Mademoiselle needed a gown according to her rank… but what was her rank? Or rather when should she be considered to have what rank? When should she be treated as Queen of Spain? Once the wedding negotiations were over? Once the engagement ceremony was over? Or after the wedding by proxy? Important questions, which not only dictated what kind of gown Mademoiselle ought to wear at what time, but also where she should be placed during all of the ceremonies.

Marie-Louise held the rank of petit-fille de France -granddaughter of France- since she was the granddaughter of Louis XIII. The Sun King had decided she should be treated as fille de France – daughter of France – as if she was his own daughter for the nuptials… but that still left the question open as to when she should be treated as Queen. It was decided to make it a gradual transition. From petit-fille de France before the engagement, to fille de France during the wedding, to Reine d’Espagne immediately after.

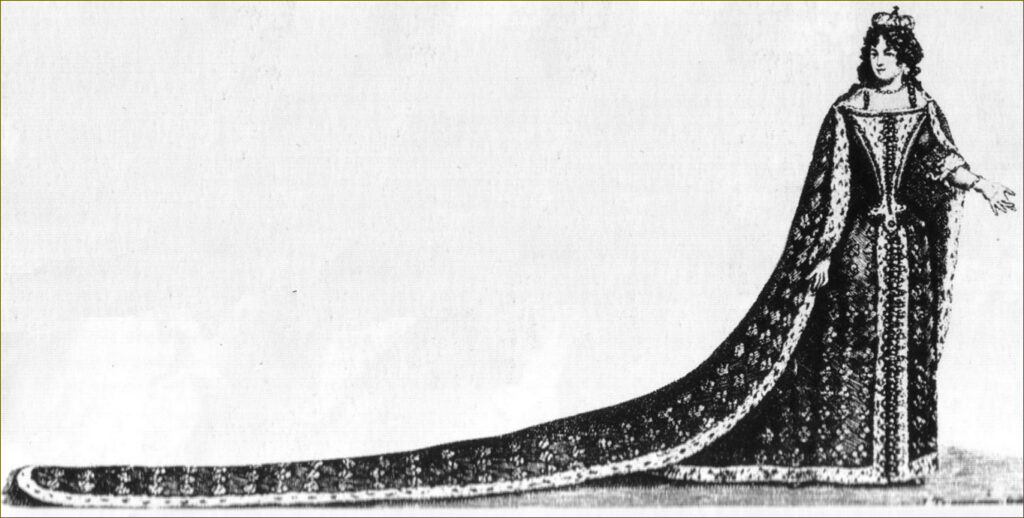

And thus, Mademoiselle’s wedding gown was less of a wedding gown and more of a coronation robe.

“Her mantle was made of violet ermine, three fingers in width joined to three rows of golden fleurs-de-lis. The train trailed six ells in length, it’s edge was spangled with four dozen golden fleurs-de-lis, full or empty, besides the three rows just mentioned. Mademoiselle’s dress was of the same fabric and colour as her mantle. This skirt was covered in front with a band of ermine, six fingers in width, joined to three rows of golden fleurs-de-lis on each side. On the bottom, it was lined with a band of ermine, three fingers in width and above it three rows of golden fleurs-de-lis. The body and the sleeves were spangled with golden fleurs-de-lis, full and empty in roughly equal number. The sleeves were lined with three fingers of ermine and all the seams, of sleeves as well as body, were covered by a one finger band of ermine. Her shows and stockings were violet, spangled with golden fleurs-de-lis.”

This wedding dress combines all three ranks…. and this solution sounds terribly easy, but was actually rather difficult. Mademoiselle was sort of between ranks and the problem was that the ladies of the same ranks as her, in this case the filles and petit-filles, could use the privileges applied to Mademoiselle via her gown to demand the same for themselves. At the same time, it had to be ensured that Mademoiselle received the honours her rank was due. A common problem at court. It often led to people simply staying away from ceremonies in order to avoid questions of precedence, which was something Louis XIV tolerated in those cases.

Three rows of golden fleur-de-lis were worn by those with the rank fille de France, while Princesses du Sang – Princesses of the Blood – were entitled to only two rows of fleur-de-lis. Some time later, the fact that Mademoiselle had worn three rows was used as a precedent to add a fourth row of fleur-de-lis to the mantle of the Dauphine. To avoid precedence issues over the fact that the edge of Mademoiselle’s mantle was spangled with four dozen fleur-de-lis, Louis XIV ordered Monsieur Sainctot, who wrote all details regarding the wedding down for the official records, to add that he was not happy with this and that it was not his intention.

The mantle length was another delicate topic. The Sun King tried to regulate the dispute over train lengths in 1666. Nine ells for the Queen, seven for the filles, and five for the petit-filles and Princesses du Sang. This wedding however introduced new lengths based on a event that took place in 1675 and now served as precedent and also the fact that Louis XIV’s illegitimate daughters would attend it.

As Turenne died in 1675, the Princesse étrangere – foreign princesses- wore trains of four ells for his funeral. Based on this, the illegitimate daughters were now granted five ells and thus received a train length privilege advantage over the Princesses belonging to foreign sovereign Houses. In order to distinguish between the illegitimate offspring and the legitimate one, the train lengths had to be adjusted accordingly. The filles kept their seven ells, which Madame, as only person considered to be a fille in 1679, wore for the wedding. Petit-filles now received one ell more and had six ells instead of only five, like Mademoiselle wore for her engagement and wedding. The six ells rule should also be applied to the Princesses du Sang in the future, but was of no immediate importance at this point, because not Princesse du Sang attended the wedding.

Mademoiselle’s head was adorned by a closed crown, decorated with Spanish fleurons, fitting her new rank as Queen. It was originally planned that Mademoiselle should be crowned immediately after the ceremony, but it was considered too much of a hassle to fasten the crown to Mademoiselle’s curls in the chapel and she thus wore it already at the start of the ceremony.

Yet another issue regarding Mademoiselle’s dress was the question of who and how many people should carry her train during the ceremonies. This was solver rather quickly, but a request of Monsieur caused a bit of chaos among the train-bearer hierarchy. Having one’s train carried was a privilege of the Royal House. Female train-bearers were for the Queen only, all others had a single male carry their trains. In case of Marie-Louise’s wedding, it was decided that Mademoiselle de Valois, her younger sister, would carry her train during the engagement ceremony. Using the wedding of Louis XIV as case of precedence, it was decided Mademoiselle would have three female train-bearers, her sister Mademoiselle de Valois, and her cousins Madame la Grande-Duchesse and Madame la Duchesse de Guise, based on the fact that Marie-Thérèse d’Autriche had three female train-bearers during the wedding ceremony in 1660.

So far so good, if it was not for a special request by Monsieur. He requested, based on 16th century precedent, that Madame would receive a female train-bearer for the occasion as well. Louis XIV made Monsieur Sainctot study the archives to find the mention in question and he did indeed find it and also a statement contradicting it. Louis decided to grant his bother’s request to please him and Madame received a female train-bearer, her dame d’honneur the Maréchale du Plessis-Praslin. This however interfered with the tradition that the Queen’s train was carried by a dame d’honneur and put Madame and the Queen in the same train-bearer privilege rank. It’s always the little things, isn’t it? Thus the Queen was upgraded from dame d’honneur train-bearer to surintendante train-bearer…. but that was a bit of a problem as well and interrupted the balance between the various office holders. In the end, the Queen went with a dame d’honneur as train-bearer for the ceremony and it seems to have been a change for the records only.

Another issue regarding the transition of ranks of the bride, was her placement during the ceremonies… and where the illegitimate offspring of Louis XIV should be placed. It was the first time Louis’ illegitimate children would attend a major ceremony and the fact that they would attend it was reason for plenty of discussion among the courtiers already.

Of Monsieur’s children, apart from the bride, only Mademoiselle de Valois, a future Queen as well, was present. The absence of Mademoiselle de Chartres, the future Duchesse de Lorraine, is easily explained with the fact that she was only three years old then. That the Duc de Chartres, future Regent of France, was not present is a little strange. It is noted that he was present at court a few days earlier, but was not present for the ceremonies. The bride and her younger sister Mademoiselle de Valois ranked as petite-filles de France during the engagement ceremony. Their papa and their step-mother along with the Dauphin, who would soon marry as well, were they only three people who were fils de France at that time.

Also present were the three still living daughters of the previous Monsieur, Gaston de France. Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, Duchesse de Montpensier, Marguerite-Louise d’Orléans, Grande-Duchesse de Toscane, and Élisabeth-Marguerite d’Orléans, Duchesse de Guise, who all ranked as petite-filles de France since they were the granddaughters of Henri IV.

Now there was a total absence of Princesses du Sang, as mentioned, and they were excused with such things as feeling unwell, could not make it or being otherwise busy. The only two members of du Sang Houses, namely of the Conti branch, present for the engagement were the Prince de Conti and his brother the Prince de La Roche-sur-Yon. The Prince de Conti had the great honour to stand in for Charles II during the wedding.

In order to fit his illegitimate offspring in, Louis XIV adjusted the internal hierarchy a bit just days before the ceremonies took place. Since his illegitimate children had been given the honours at court, it was argued, they should be also be allowed to attend royal ceremonies. The honours they had been given at court, were some of the same the du Sangs enjoyed. Like handing Louis his shirt. Thus present at the ceremonies where: Mademoiselle de Blois and her brother the Comte de Vermandois, whose mother was Louise de de La Vallière. Along with the Duc du Maine, who was Louis XIV’s favourite son, and his sister Mademoiselle de Nantes, whose mother was Madame de Montespan. And in order to make it look like the Sun King did not favour his own illegitimate offspring over other royal illegitimate offspring, he also invited the Duc and Duchesse de Verneuil. The Duc being a son of Louis XIV’s grandpa Henri IV and his mistress Catherine-Henriette de Balzac d’Entragues.

A slightly elevated platform was set up for the engagement ceremony on which all previously mentioned attendees were placed in order of rank in a semi-circle. They were joined for some moments of the engagement by the Spanish ambassador and officers essential for the ceremony. The King and Queen formed the centre and were seated. The Dauphin, to the right, and Monsieur, to the left, formed the next row as the next highest ranking members of the royal family. Madame, to the right, and Mademoiselle, to the left, formed the third row. Mademoiselle de Valois and la Grande Mademoiselle formed the fourth row. The Grande-Duchesse de Toscane and the Duchesse de Guise formed the fifth row. The Prince de Conti and the Prince de La Roche-sur-Yon formed the sixth row as Princes du Sang. The Comte de Vermandois and the Duc du Maine, as eldest attending illegitimate sons of Louis XIV, formed the seventh row. Mademoiselle de Blois and Mademoiselle the Nantes formed the eight row. The Duc and Duchesse de Verneuil formed the last row.

This set up was carried over the the wedding ceremony, just that it was more elaborate and the position of the bride was changed. The dais for the wedding was of course more prestigious looking compared to the engagement one and it were again the seemingly little things that marked who was a bit more important than the other important people. Louis XIV and Marie-Thérèse formed the centre again. They were seated on armchairs under a canopy right by the altar and had each a prie-Dieu at their disposal and a carpet, violet velvet with embroidered golden fleur-de-lis, beneath their feet. Again in a semi-circle and with the carpet below their feet, were placed the Dauphin, Monsieur, Mademoiselle, to mark that she was regarded a fille de France for the wedding, while she had the position of petit-fille for the engagement, and Madame. Mademoiselle was here already placed before Madame, yet below the Queen. All four of them had cushions and stools. The next row consisted of the petit-filles and they were placed just at the edge of the carpet. Just outside the carpet, followed the Princes du Sang and below them, towards the edge of the dais, where the illegitimate children. Each of those last three rows had a cushion at their disposal.

Once the wedding ceremony was over, Marie-Louise changed positions again. She was now officially Reine d’Espagne and as such placed among the royale couple. She was now also, as Queen of a foreign Kingdom, a royal guest of the Kingdom of France. As such she received the place of honour between Louis XIV and Marie-Thérèse.

Another quite interesting etiquette-issue regarding the wedding ceremony was the question as to if the Prince de Conti had to cede to the Spanish ambassador. There were always etiquette questions as to how ambassadors should be treated, since they were private persons with their own titles, but at the same time the reflected the power of their sovereigns. Louis XIV had ordered that the Princes du Sang should not cede, without order, to the Spanish ambassador. This wedding was a special case, because both the ambassador and the Prince de Conti, standing in for Charles II, represented the same person. Who of them was, at that point, representing the King of Spain more? It was decided that the Prince de Conti as proxy-groom had the upper hand, but the Spanish ambassador could only be made to cede to Conti after written assurance that this would not be used as case of precedent for other occasions.

Of course the whole did not go without incidents etiquette-wise. During the wedding ceremony, the King’s Almoner did a sneaky move and got a Bishop he did not like to salute the King and Queen. Which gave the Almoner the time to get into a better place, which the Bishop had previously, to present their Majesties with the Book of the Gospel.

Now you might have noticed a very prominent lack of one certain name thus far. A name belonging to the House of Bourbon… that of Condé. The head of the Condé-branch was the most senior Prince du Sang and surely, if the slightly lower ranking Contis were there… the Condés should be too? But they were not and the reason for it, is one of those things that appear quite trivial for us today, but were of the utmost importance back then. Monsieur le Prince (aka le Grand Condé), the head of the House, and Monsieur le Duc, his son and heir, were not present over a dispute of the plume. To understand that, we have to get back to the engagement ceremony again.

The contract of marriage was read during the engagement ceremony and then signed, according to rank. Monsieur de Saintot describes it the best: “Monsieur de Pomponne (Secretary for Foreign Affairs) had hardly read the titles of the contract, when the King said that it was enough and the the contract brought to him for signing. The King and Queen signed seated, Monsieur de Pomponne having presented the pen to them and taken it back from their hands. Monseigneur the Dauphin, Monsieur, Madame, Mademoiselle the bride, Mademoiselle de Valois, Mademoiselle d’Orléans (Grande Mademoiselle), Madame la Grande-Duchesse and Madame la Duchesse de Guise all signed in the same column the King and Queen had signed, then pen also having been presented to them by Monsieur de Pomponne, who then took it from the hands of Madame de Guise and returned it to the ink well. Then the Prince de Conti took it and signed immediately below Madame de Guise as Prince du Sang. This status was more advantageous to him that that of proxy, which would have made him sign in the second column, a little below Madame de Guise. The Prince de La Roche-sur-Yon, Monsieur de Vermandois, Monsieur du Maine, Mademoiselle de Blois, Mademoiselle de Nantes, and Monsieur and Madame de Verneuil all signed in the first column too, taking the pen themselves from the well and returning it there after signing. The ambassador alone signed in the second column, opposite of the space between the signature of Madame de Guise and that of the Prince de Conti. During the signature of the contract, the King and Queen remained seated, the Princes and Princesses approached the table to sign according to their rank and saluted the King and Quenn as they drew back.”

What does that have to do with the Condés? The plume -pen- is the object of controversy that made them stay away. Like Monsieur de Saintot states, some were presented with said pen and then the pen was taken from them again, while others had to take the pen and return it by themselves. The King and Queen, according to etiquette, never take something. Everything, and may it be a glass of wine, has to be presented to them. This goes for this prestigious pen as well and the pen rule also applied to the filles and petit-filles. All of them were presented with the pen and it was then taken from their hands. Monsieur le Prince insisted that he and his son should also be presented with the pen instead of having to take and return it themselves.

It was argued that this claim was invalid based on the fact, that the Duc d’Enghien had signed marriage contracts without being presented with the pen in the past. The Condés were not happy with that at all, but since the Duc had indeed taken the pen himself recently, there was not much they could do… apart from staying away and thus avoiding another case that could be used as precedent against them in the future.

This are just some questions of etiquette that arose in regards of the wedding. Others involved as to when Mademoiselle should be called Madame. The Spanish wanted to use the term in the contract already, but Louis XIV disagreed. Or how certain other people should be addressed during and after the wedding. In the end, the ceremonies went well. The new Queen remained in France for a while and received all the honours due to her. She departed with plenty of tears, but once in Spain she soon realised that her husband, despite all the flaws, was not too bad to get along with it.